BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

High-Rise Gospel Presence: A Case for Neighborhood Chaplains

Neighborhood Chaplaincy is an innovative approach to ministering the love of Jesus in emerging communities. Steve Daman makes the case for how Boston would benefit from neighborhood chaplains.

High-Rise Gospel Presence: A Case for Neighborhood Chaplains

By Steve Daman

In recent blogs, we’ve been talking about Boston’s soon coming population increase and asking how the Church might prepare for that growth. Will some of Boston’s 575 existing churches rise to the challenge and create relational pathways to serve the many new neighborhoods being planned and built in Boston?

We hope they will, and that church planters will pioneer new congregations among Boston’s newest residents. But can we do more? Might there be other ways to bring the love of Jesus into brand new communities?

Asking the Right Questions

Dr. Mark Yoon, Chaplain at Boston University and former EGC Board Chairman, starts with a question, not an answer. “The first question that comes to my mind is: who are the people moving into these planned communities? Why are they moving there? What are the driving factors?”

According to Dr. Yoon, thoughtful community assessment would be the obvious starting point. To launch any new outreach into these neighborhoods will require “serious time and effort to get this right,” he says. “Getting this right” will likely require innovative solutions.

Let’s assume, for example, that a community analysis shows that many of Boston’s newest residents are young, urban professionals. Dr. Paul Grogen, President & CEO of the Boston Foundation, noted recently, “Boston is a haven for young, highly educated people. Boston has the highest concentration of 20-to-34-year-olds of any large city in America, and 65 percent of Boston’s young adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher”, compared with 36 percent nationally.

If the people moving into these new communities are affluent, educated young people, it is likely that many may be what statisticians are calling nones or dones.

Nones are people who self-identify as atheists or agnostics, as well as those who say their religion is “nothing in particular.” Pew Research finds nones now make up 23% of U.S. adults, up from 16% in 2007.

Sociologist Josh Packard defines dones as “people who are disillusioned with church. Though they were committed to the church for years—often as lay leaders—they no longer attend,” he says. “Whether because they’re dissatisfied with the structure, social message, or politics of the institutional church, they’ve decided they are better off without organized religion.”

Adopting New Church-Planting Models

It would seem likely that the dones and nones won’t be looking for a church in Boston—at least not the kind of church they have rejected.

“To make inroads into these communities,” Dr. Yoon continues, “one’s gospel/missional perspective will be paramount. Most of our church leaders have old church-planting models that focus on certain attractions they roll out.”

What will be required instead, he says, is a church-planting model “built on vulnerability and surrender, and skill on how to engage, and prayer.” This combination, he feels, although essential for the task, will be “a rare find!”

What, then, might be some non-traditional ideas for establishing a compelling Gospel presence in a brand new, affluent, high-rise neighborhood?

Neighborhood Chaplaincy

What if Christians embed “neighborhood chaplaincies” into emerging communities? Rather than starting with a church, could we start with a brick-and-mortar service center, positioned to help and serve and love in the name of Jesus Christ?

Imagine a church, or a collaborative of churches, sending certified chaplains into new communities to extend grace and life in nontraditional ways to new, young and/or affluent Bostonians. Could this be a way to implant a compelling Gospel presence among this population?

Picture a storefront in sparkling, new retail space—a bright, colorful, inviting and safe space where residents in the same building complex might make first-contact. I envision a go-to place for any question about life or spirit, healing or wholeness, a place where there is no wrong question, where Spirit-filled Christians are ready to listen and offer effective help.

The neighborhood chaplaincy office may serve as a non-denominational pastoral counseling center, offer exploratory Bible classes, and sponsor community-building events. As with workplace chaplains, neighborhood chaplains may serve as spiritually aware social workers, advising residents about such issues as divorce, illness, employment concerns, and such. They may be asked to conduct weddings or funerals for residents. As passionate networkers, they would serve residents by pointing them to local churches, agencies, medical services, and the like.

Community Chaplain Services (CCS) in Ohio provides one intriguing ministry model. According to their website, CCS “is designed to offer assistance to those in need, serving the spiritual, emotional, physical, social needs of individuals, families, businesses, corporations, schools, and groups in the community.” This ministry grew from a community-based café ministry into a full-service educational resource and pastoral service provider.

Other than this one example, a quick web survey uncovers little else. Given the ongoing worldwide trend toward increased urbanization, coupled with the biblical mandate to make disciples of all nations, including the urbanized communities, the lack of neighborhood chaplaincy models is surprising. One would think the idea of embedded chaplaincy among the affluent would have taken root by now.

CURRENT Chaplaincy Models

Certainly, the core idea of chaplaincy has been around a long time and has seen various expressions around the world. One can find chaplaincy venues such as workplace and corporate, hospitals and institutions, prison, military, public safety (serving first responders), recovery ministry chaplains, and more.

Community chaplaincy in high-crime or low-income neighborhoods is also widespread. Here in Boston, the go-to person for this kind of urban community chaplaincy is Rev. Dr. LeSette Wright, the founder of Peaceseekers, a Boston-based ministry working to cultivate partnerships for preventing violence and promoting God’s peace, and a Senior Chaplain with the International Fellowship of Chaplains.

Through Peaceseekers and other partners, Rev. Dr. Wright initiated the Greater Boston Community Chaplaincy Collaborative, which has trained over 100 people to serve as community chaplains. Rev. Dr. Wright says their main work is to be a prevention and response team, “quietly serving in diverse places" to provide spiritual and emotional care among New England communities.

Trained chaplains minister "everywhere from street corners to firehouses to homeless shelters, barber shops, nursing homes, boys’ and girls’ clubs; meeting for spiritual direction with crime victims, lawyers, nurses, police officers, doctors, construction workers, students, children, clergy, etc.”

“We do not have a focus on the affluent or the new high rises,” Rev. Dr. Wright admits. “We do not exclude them, but they have not been a primary focus.”

Who Will Pay For It?

Rev. Dr. Wright says that the biggest challenge she has faced establishing a network of community chaplains in Boston is funding. Some churches and denominations have provided missionary funding for chaplains. She says the interest and openness from the community for this initiative is high, and “with additional funding and administrative support in managing this effort we will continue to grow as a chaplaincy collaborative.”

If Boston were to plant neighborhood chaplaincy programs in new, emerging, affluent districts, funding would still be an issue.

Rev. Renee Roederer, a community chaplain with the Presbyterian Church in Ann Arbor, Michigan, has been writing about this kind of outreach, asking the same questions. “What if we could call people to serve as chaplains for particular towns and neighborhoods, organizing spiritual life and community connections in uncharted ways?” she writes. “Who will pay for it?”

Rev. Roederer further considers, “What would be needed, and what obstacles would have to be cleared, in order to create such roles? What if some of our seminarians could serve in this way upon graduation?”

“I’m a realist, knowing it would take a lot of financial support and creativity to form these kinds of roles,” she says, “but the shifts we're seeing in spiritual demographics are already necessitating them.”

TAKE ACTION

Attend a Discussion Group

Are you interested in joining a follow-up discussion with other Christian leaders on the potential for Neighborhood Chaplaincy in Boston?

Go Deeper

We have more questions than answers! Check out the questions we're asking as we consider fostering a Neighborhood Chaplaincy movement in Boston.

Learn More

WHAT DID YOU THINK?

From the Bible Belt to Boston: What God's Doing in New England

Are you ministering in a spiritual desert? In a recent study, Boston was ranked one of the most “Post-Christian” cities in the U.S. Kathryn Hamilton, an EGC communications intern from West Texas, weighs in about her experience with Boston’s spiritual climate and Christian vitality.

From the Bible Belt to Boston: How God’s Moving in New England

by Kathryn Hamilton

Do the numbers lie?

In the most recent “post-Christian” study by Barna Group, a research organization focused on the intersection of faith and culture, Boston ranked 2nd among “The Most Post-Christian Cities in America: 2017.” In fact, eight out of the top 10 are located in the Northeast, five of which are located in New England.

To qualify as “post-Christian” for Barna’s study, individuals had to meet nine or more of Barna’s 16 criteria that indicate “a lack of Christian identity, belief and practice, including, individuals who identify as atheist, have never made a commitment to Jesus, have not attended church in the last year or have not read the Bible in the last week.”

As I reflect on my two months interning for EGC and prepare to return home to my “Bible-Belt” town in West Texas, I find myself a bit baffled, as my experience has been far from spiritually dry and Godless.

“Saying you’re a Christian in Boston is weighty. There is no cultural norm influencing your religious affiliation. ”

Knowing the Lord was calling me to Boston, it was seeing numbers Barna posted in 2015 that sparked my initial interest – that Boston ranked 4th among the top dechurched cities. However, as I settled into my temporary home in Cambridge and plugged into a local church there, I was in awe of how “Christian” the Christians in the Boston area were.

Cultural Christianity is prominent in my region of Texas. You grow up “Christian,” go to church on a regular basis (or at least on Christian holidays) and hold to what you consider “good Christian morals.” You hear the Gospel preached so much that the meaning numbs and you fall prey to the comfort and ease of day-to-day life.

Let me disclaim, this is a broad generalization. I'm where I am spiritually because of devoted and loving Christian parents and mentors that demonstrated the hands and feet of Jesus. I generalize the culture of the Bible Belt to make the point that saying you’re a Christian in Texas and saying you’re a Christian in Boston can reveal starkly different fruit. Saying you’re a Christian in Boston is weighty. There is no cultural norm influencing your religious affiliation. You’re a Christian because you choose to follow and live for Jesus.

The Christian community that I have found here in Boston is unlike anything I’ve seen or experienced before. The community seen in the early church of Acts is still alive, and, from my experience, flourishing. It’s small but strong.

They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer. Everyone was filled with awe at the many wonders and signs performed by the apostles. All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need. Every day they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts, praising God and enjoying the favor of all the people. And the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved.

Acts 2:42-47 has been my Boston.

Where I thought there was going to be nothing but pluralistic, moral relative doctrine, I have found sound, Gospel-oriented teaching. Where I expected to see scattered believers, I have seen great unity. Where I knew social injustices and needs to be present, I saw the church on the front lines. Where I expected to be a lone believer and disheartened by the lack of believers, I’ve been the one nurtured and influenced.

“Where I expected to see scattered believers, I have seen great unity. Where I knew social injustices and needs to be present, I saw the church on the front lines.”

So if Boston Christian community is anything like the early church, the Lord is going to “add to their number daily” those who are being saved.

I’m sure that Barna’s numbers are accurate, and that Boston is in fact one of the most post-Christian cities in America. But as church planters who come to Boston because of that number partner with and learn from the Christian vitality already here, the fruits of both their labors are multiplying.

Seeds are being sown on good soil in Boston, and a revival is growing roots.

RESPOND

Are you from the Bible Belt? Do you agree? Disagree? Have a different experience? I'd love to hear from you!

Are you interested in internships with EGC? We have volunteers, interns, associates, and fellows working with us each semester.

About the Author

Kathryn Hamilton is a Summer 2017 Communications BETA at EGC. She graduates in 2018 with an Advertising and Public Relations major from Abilene Christian University. Growing up in the church in Dallas and Abilene, TX, she developed a heart for missions among unreached people groups. After graduation, she plans to work in the non-profit sector or with corporate social responsibility. In Boston, she has enjoyed the diverse culture, the "T", lots and lots of J.P. Licks and, of course, the people.

What's Next: My 5 Dreams For Church Planting in Boston

Rev. Ralph Kee, animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, has been giving a lot of thought to this idea: What may be the Church’s dreams for Boston for the next few decades? What should be the Church’s priorities? Where are the Church’s growth edges? In this article, Ralph offers his own five basic ideas, his five dreams about church planting for Boston’s future.

What’s Next: My 5 Dreams for Church Planting in Boston

by Rev. Ralph Kee, Animator, Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative

Where are we headed as the Church in Boston? What might be some goals, dreams, and potential growth points for the Body of Christ in Boston over the next several decades?

As I’ve engaged with the Boston 2030 initiative, I’ve been giving a lot of thought to what it means for Christians in the next several decades. Here are my dreams about Boston’s church planting future:

Dream #1: Holistic Churches Multiplying Churches

I see Boston filled with Gospel-permeated, holistic churches.

By holistic churches, I mean those that serve the city with the whole Gospel by ministering to the whole person. I think that’s what God dreams and wants for Boston, because that’s what he wants for all his created people. Paul writes, “God has made known to us the mystery of his will,” and his will is “to bring all things together in Christ, both things in the heavens and things on the earth.” (Eph. 1:9,10)

Boston is staged to grow. I moved to a Boston of 641,000 in 1971. By Boston’s 400th birthday in 2030, the population is expected to jump to 724,000 or more. In light of this growth, we at the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative have been asking two key questions:

1. Where will these new Bostonians live? Whole new neighborhoods are underway to house several thousand people each, all within Boston’s city limits.

Learn More: Where to Plant a Church in Boston: Areas of Growth

2. Where will these new Bostonians go to church? Will the Church be ready? Who will lead the way to envision new expressions of Church for new Bostonians? The apostolic task of the Church, a leading task from Ephesians 4:11, is to multiply communities of faith—churches multiplying churches. Let’s do it!

Learn More: Multiplying Churches in Boston Now

Dream #2. Both Gentrifiers and Born-Bostonians Playing a Part

I see Gospel-entrenched gentrifiers and neighborhood-based Christian activists together salting the city.

Boston is becoming more and more gentrified. Researchers spot gentrification where census tracts show increases in both home values and in the percentage of adults with bachelor’s degrees. I’ve had to come to terms with the fact that in the neighborhood where I’ve lived for 46 years, I too, am a gentrifier.

Today, gentrifiers include young Christian professionals moving into older neighborhoods all over the city to be salt and light, to love their neighbors, to do Jesus-style thinking and living in that neighborhood. These folks can be “entrenched gentrifiers,” incoming residents who, in their own minds and hearts, want to appreciate and have purposeful “attachment to the local meanings, heritage, history and people” they are now living near.

For example, intentional Christian communities—where several families or singles live together in shared commitment to each other and to their neighbors—are flourishing.

Boston’s "Gospel-entrenched gentrifiers", as I call them, are not pioneers, but reinforcements. They join embedded Kingdom builders—second-, third-, and many-generation Bostonians—Christ-followers who are dreaming big dreams for their neighborhoods.

“Boston’s Gospel-entrenched gentrifiers, as I call them, are not pioneers, but reinforcements.”

One such Kingdom builder is Caleb McCoy, a fourth-generation Dorchester resident and EGC’s Development Manager. Caleb has a homegrown knowledge of and love for the city. He says, “I believe my role in the church is to help make the Gospel relevant and personal to people that may not feel that God’s plan applies to them.”

Caleb’s vision is to use his musical and communications gifts to inspire “a revival of young and middle-aged adults, joined together, exemplifying the Gospel through preaching and the arts.”

I am excited about Caleb’s vision. I have a dream that such neighborhood-based Christian activism will be the engine to drive effective ministry today and tomorrow.

Dream #3. Relevant, Hands-On Ministry of Reconciliation

I see today’s Boston’s Kingdom citizens reconnecting what has been severed by sin.

I am dreaming that Boston’s visionary, prophetic Christians will, with God-inspired imagination, help build new communities of faith. These newly imagined churches will demonstrate the Kingdom of God in today’s urban context.

The prophetic task, as I see it, is to cast a vision for a redeemed creation. Empowered by the Spirit of God, today’s prophets can work to reconnect what was disconnected by sin.

When sin entered the world, it entered the whole world—not just the human heart, but the very heart of the created order. Original sin instantly caused four original schisms, (Learn More: The Prophetic Task):

humanity separated from God

humanity separated from the created order

man separated from woman

people separated from people

What is to be done about these painful schisms? Thankfully, they are all resolved in Christ, as we the Church fulfill the prophetic task! We proclaim the Kingdom of God, and partner with God in his work of connecting, redeeming, healing, and bringing Kingdom-of-God life and peace to every facet of Boston.

Consider the refugees coming to Boston today. What will they find? Will they experience more schism in their torn lives? Or will some neighborhood church in Boston welcome them, embrace them as valued people loved by God, and begin to effectively reverse the curse of schisms in their lives by loving them well? (Learn more: Greater Boston Refugee Ministry).

And if some Boston residents were to observe Christians living in their neighborhood, reversing the curses of the four schisms, would these observers not be more ready to listen to the spoken Gospel message?

Dream #4: The Good News Proclaimed in Boston’s Heart Languages

I believe God is calling evangelists to speak the Gospel in the languages of Boston.

I want to see Boston gifted with many evangelists, men and women who can speak and live out the Gospel in the languages of Boston’s old-timers, of second- and third-generation Southies, or Townies, or Dorchesterites. Who will speak the Gospel to:

the retired men of South Boston who hang at the coffee shop every day?

the women who gather at Ramirez Grocery or Rossi Market?

the generations of men and boys who gather at the corner barbershop?

the freshmen or grad students at BU or BC or MIT?

those who speak the 100+ languages of newcomers arriving from the four corners of the earth?

We know the Gospel is two handed: word and deed. We need to do both: preach the Word and do the Gospel.

Today particularly, we need to be careful not to focus only on meeting basic needs and neglect preaching. One follows the other. After neighborhoods see the Gospel in action, I think they will be more ready to have someone fully explain it to them and invite them to believe in Jesus themselves. Show and tell.

Who of those already living in Boston are called to evangelistic preaching in Boston specifically? Who yearns to spend their lives preaching the Gospel in Boston? Do you?

In Romans, Paul asked, “And how can they believe in the one of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone preaching to them? And how can anyone preach unless they are sent? As it is written: ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!’” (Rom. 10:14,15)

Dream #5. Church Planters Collaborating Closely

I want to see church planters in Boston thinking of themselves as players on a Boston-wide team.

The Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative started gathering in 2000, and we chose the word “collaborative” intentionally. In the Book of Acts, the story of early church planting, we see nothing but collaborative ministry efforts. One church, one basic team, one overarching goal everyone shared and worked toward—that’s the Acts of the Apostles.

Collaboration is basic to church planting—and so it should be in Boston. I want to see Boston’s church planters meeting face to face, setting shared goals, being mutually accountable and passionately focused.

I imagine church planters setting Boston-wide church-growth and church-planting goals collaboratively. I envision shared strategies to cover ground and to plan over time—setting 6-month, 12-month, 2-year, and 15-year goals.

“How long will it take you to build the wall, Nehemiah?” King Artaxerxes asked (Neh 2:6). Nehemiah, a slave in a foreign land under a tyrant, was the last person in a position to guarantee any purpose-driven time goals. But he did tell Artaxerxes a time goal, because he had to. And they met it—the collaboration of faithful residents working side by side in Jerusalem finished the wall in fifty-two days!

Let’s collaborate, set some prayerful goals, and see the work get done!

To see the full-length article, click here: I’m Dreaming About Boston’s Future—Are You?

TAKE ACTION

So those are my five big church planting dreams for Boston. What do you think? Are you dreaming with me? Dream big! When we get some more ideas, we’ll share them in a future post. Send me an email—I would love to hear from you.

Are you a church planter? I invite you to join us at the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative!

Ralph Kee came to Boston in 1971 to help plant a church emerging out of the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s neighborhood outreach. Starting churches became his clear, lifelong calling. He has since been involved in launching or revitalizing dozens of churches in and around Boston. In 2000, Ralph started the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, a peer mentoring fellowship to encourage and equip church planters. Today he spends time mentoring church planters, mostly one-on-one, usually over coffee.

Tips for Developing Church Leadership

Starting a new church, but short on leaders? A few years ago, we interviewed a number of Greater Boston’s church planters to ask how they were developing new leaders for their churches. Here are some of their tips for raising new leaders.

Tips for Developing Church Leadership

by Rudy Mitchell and Steve Daman

Starting a new church, but short on leaders?

A few years ago, we interviewed a number of Greater Boston’s church planters to ask how they were developing new leaders for their churches. Here are some of their tips for raising new leaders.

1. Pray first. While you might be thinking you need people with particular skills, what you really need are people with spiritual maturity and Christ-like character. These foundational qualities take time to develop and time to discern. Lining up leadership should not be rushed. Do what Jesus did before he chose his team. Get up on the mountain and pray.

2. Examine and test. You don’t want to rush into appointing someone as a leader until you have thoughtfully and prayerfully assessed their potential and discovered their passion. To get there, you’ll need sufficient face time to begin to listen to their hearts.

- Motives: Ask them to tell you their story about their calling to serve Christ and his church, and see if you can discern their motives for accepting a leadership role.

- Beliefs: Are their beliefs sound and consistent with Scripture and with the church’s vision?

- Character: Are they teachable? Faithful? Humble? Do they love Jesus?

- Skills: Talk openly about the candidate’s strengths and potentials, but also weaknesses and limits. (You might go first in this one.)

- Vision: Ask them about their vision for the position and brainstorm together what it might look like for them to take leadership over a particular ministry. See how that conversation goes.

Don’t be afraid or embarrassed to implement this type of assessment as it may save both you and the candidate much pain and difficulty if, in fact, it turns out they are not the right person for the job. For scriptural precedent on testing, read 2 Corinthians 13.

3. Make disciples. Developing leaders can look exactly like making disciples.

- Replicate yourself: Move beyond the rigid supervisor/supervisee relationship and consider that your goal is to replicate yourself, to pass the torch to others who can learn to do the work even better than you do.

- Spend time together: Training, discipling and mentoring require that you and the emerging leader spend time together and become part of each other’s lives in a deep and meaningful way.

- Lean in: Lean in to the relational aspect of leadership development. Make yourself available. Listen well. From listening will grow understanding, spontaneous prayer, love, and maturity.

- Huddle up: Add a regular Bible study time with your mentee with an eye toward applying what you learn reflecting on Scripture to ministry and life situations. This kind of intentional discipling can be one-on-one or in small huddles of three or more.

- Grow yourself: With humility, remember that iron sharpens iron, and through this relationship, you’ll be changing and growing, too.

4. Learn together. Add to the essential, relational side of leadership development some formal training and exploration. Look for opportunities to gain knowledge and insight together.

- Create training opportunities: Learning can happen in regular leadership meetings, special training sessions, or on retreats. Listening, vision casting, and discussion can all help.

- Pick resources: Choose books or articles, and maybe online resources or video series that your team can study and discuss.

- Flex scheduling: If team members seem too busy or have conflicting schedules, you might be able to provide some training through virtual online meetings, one-on-one or in groups.

- Back to school: See what’s available at local Christian colleges, Bible institutes, and seminaries. Encourage your emerging leaders to pursue and gain academic credentials along with practical knowledge. The learning and the credentials may open doors for them for even more effective ministry.

5. Do and reflect. When it comes to raising up leaders, nothing can substitute for hands-on-experience and on-the-job training. Perhaps your church or ministry can offer internships, residency, or apprenticeship training. In the same way that Jesus’ disciples watched and followed, listened and asked questions, and then were sent out, follow that pattern.

- Show and send: After instruction in and modeling specific skills in real life ministry with your mentees along for the ride, start delegating responsibilities and monitor how it goes. Let them lead a small group, or teach a lesson, or get out and get dirty serving.

- Reflect and send again: Observe, supervise, and coach. Give feedback. Reflect together what happened. Pray together. Send them out again.

A couple final hints:

- Articulate roles and responsibilities: Make sure the new leaders can articulate back to you their responsibilities and what they are accountable for so that your expectations and theirs are always in sync.

- Shepherd their hearts: Periodically discern if the leaders find joy and fulfillment not only in doing the work of ministry, but in learning to do it better.

SOURCE: In 2014, the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s Applied Research team completed 41 in-depth interviews with Boston area church planters of various denominations, ethnic groups, and church planting networks. This article was derived largely from responses given by these church planters regarding their own practice and view of leadership development, with added insights from the EGC Applied Research team.

TAKE ACTION

Connect with church planters: Visit the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative.

History of Revivalism in Boston

Journey with EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell through Boston’s key evangelistic revivals from the First Great Awakening in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign of 1950. History comes alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through gifted evangelists, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

History of Revivalism in Boston

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 24 — January/February 2007

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Read the full version online here.

Executive Summary

“Revivalism,” according to the Dictionary of Christianity in America, “is the movement that promotes periodic spiritual intensity in church life, during which the unconverted come to Christ and the converted are shaken out of their spiritual lethargy.” David W. Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland and a distinguished visiting professor of history at Baylor University, describes revivalism as a strand of evangelicalism, a form of activism (which he identifies as one of evangelicalism’s four key characteristics), where a movement produces conversions “not in ones and twos but en masse.”

Dwight L. Moody revival meeting in Boston

In this 2007 study, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell traces Boston’s key evangelistic revival movements from the First Great Awakening in Boston in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign in Boston, starting on New Year’s Eve in 1949. With 23,000 attending services on the Boston Common in 1740 to hear Whitefield (without the benefit of electronic amplification) to an estimated 75,000 gathered at the same spot in 1950 to hear the same Gospel preached by Rev. Billy Graham, the story of revivalism in Boston gives color and texture to the waves of revival.

Rudy introduces us to a few of the key players, remarkable crowds, recorded outcomes, while weaving in familiar faces and places, from Charles Finney, Dwight L. Moody and Billy Sunday to Harvard Yard, Park Street Church and the Boston Garden. We sense history coming alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through his gifted evangelists and preachers, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

“History of Revivalism in Boston” was first printed in the January/February 2007 issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, Issue 24. It was subsequently published in New England’s Book of Acts, a collection of reports on how God is growing the churches among many people groups and ethnic groups in Greater Boston and beyond.

Table of Contents (with key themes and names added)

First Great Awakening in Boston

Learn More

Read the full version of “History of Revivalism in Boston”

Contact Rudy Mitchell with questions, or to request a printed copy.

Report from the 2017 New England City Forum

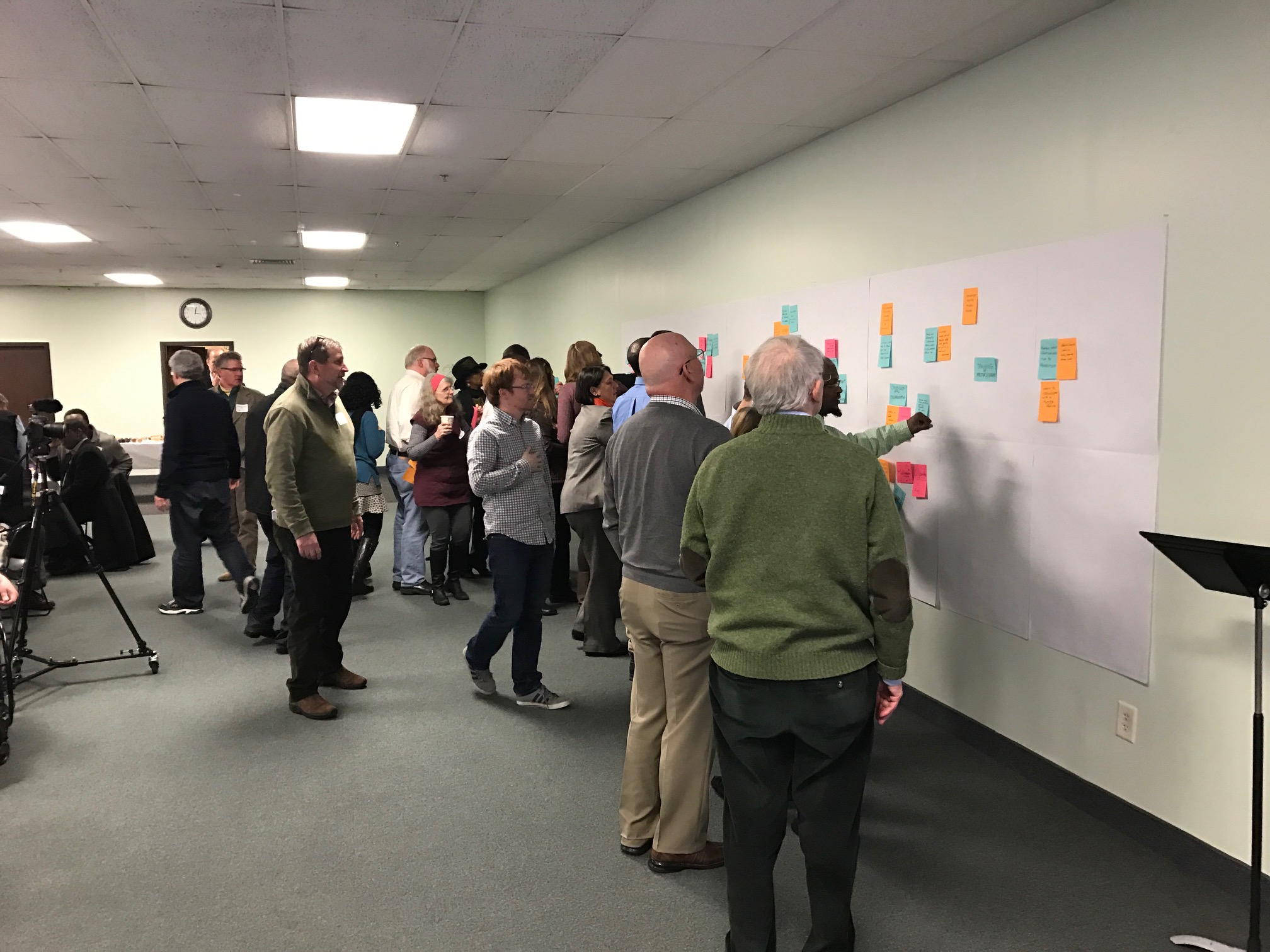

The New England City Forum brought together 103 Christian leaders from across New England to learn from each other, develop deeper relationships, and ultimately increase effective ministry in each of our cities.

Report from the 2017 New England City Forum

by Kelly Steinhaus

OVERVIEW

The New England City Forum brought together 103 Christian leaders from across New England to learn from each other, develop deeper relationships, and ultimately increase effective ministry in each of our cities. We met on February 16, 2017 at First Assembly of God in Worcester.

The New England City Forum is sponsored by the Emmanuel Gospel Center (Boston), Vision New England, Greater Things for Greater Boston, and the Luis Palau Organization (who bought us lunch!).

The New England City Forum is linked intentionally with Vision New England’s GO Conference, which this year was February 17 and 18 at the DCU Center in Worcester.

OPENING PRESENTATION

Jeff Bass and Liza Cagua-Koo from the Emmanuel Gospel Center shared a Powerpoint Presentation about the complexity of effective ministry. God’s work in a city is hard to understand because we often don’t see important things, nor do we interpret what we do see effectively. Because different people see things in different ways, and our biases interfere with our seeing and our understanding, we will be more effective in ministry if we can look and interpret together. This points to the importance of strong, diverse relationships within our ministry teams, and across our collaborative networks, as we work together to advance the Gospel in our cities and regions.

CITY PRESENTATIONS

We heard stories from Worcester, MA; Portland, ME; New London, CT; and Rhode Island.

Here are some highlights of what we learned from the various presentations.

Leaders from Worcester

Worcester, MA

The second-largest city in New England, Worcester is an ethnically, racially, culturally and socio-economically diverse urban center where the church is starting to leverage the strategic opportunities presented by its diverse community. Although historically a more siloed and isolated city, here Christians are coming together to serve their neighbors. The Worcester team highlighted collaboration efforts around Christian sober house "Turn The Page" and the work of Worcester Alliance for Refugee Ministry (WARM), which connects urban and suburban churches together to welcome the city's incoming refugee neighbors. In fact, Worcester has the highest number of refugees of any city in Massachusetts. Ministry efforts in Worcester are undergirded by Kingdom Network of Worcester, which is a strong inter-denominational prayer movement, and John 17:23 pastoral support groups. The group compiled a handout describing an overview of the history of God's work in Worcester, its current challenges and opportunities.

Portland, ME

Portland's presentation highlighted the rising percentage of church attendance: older churches are being revitalized and new churches are being planted. These churches are strengthened through the Mission Maine pastors group which meets monthly to collaborate in mission and fellowship. Ministry in Portland is characterized by strong compassion-based ministry. To address the drug/opioid epidemic, the Root Cellar community center provides after-school programs, food, and clothing. Portland also has a large percentage of immigrants, and the largest number of asylum-seekers in New England. Churches have come together to help the immigrant community through trauma and marriage/family counseling, individual discipleship, language instruction, and legal services. Additionally, a team of street pastors from various churches are sharing the gospel with folks on the street, and they have seen a decrease of 70% of crime in the neighborhoods where they have been serving!

New London, CT

CityServe eCT is an informal network of churches and ministries united to proclaim the gospel in word and deed through collaboration for prayer, outreach, and service. With a 40-member team of ministry leaders and no paid staff, they have come together for a variety of efforts including: restoring Fulton Park; hosting a CityFest festival in the park (attended by 1,200 with 90 people taking steps of faith); through a "Love 146," training of staff in motels to recognize signs of trafficking and child exploitation; developing a team of police chaplains; and coordinating a multi-church vacation bible school. Many more joint initiatives are planned for the coming months. Check out their Powerpoint and Notes to learn more!

Rhode Island:

Inter-church collaboration in Rhode Island began with approximately 100 pastors participating in prayer summits and monthly pastors’ breakfasts. This led to a desire to work together, and the organization Love Rhode Island emerged, which encourages churches to pray for people, to care in practical ways, and to share the good news of Jesus. Love RI held a large citywide gospel festival in 2010 that was attended by over 100 churches. They also began to bring together entire congregations for prayer through People’s Prayer Summits. In 2013, the Summer OFF (Outreach, Friends, and Faith) program developed, which is a vacation bible school on wheels with 13 churches, bible stories, free lunches, and crafts. Then, in 2016, the Together initiative trained pastors and leaders in servant evangelism, intercession, and church planting. This ministry is now launching “Together we Pray,” 35 churches engaged in 24/7 prayer for the region. Learn more with their Powerpoint and Handout.

TABLE DISCUSSIONS

A key feature of the forum was table discussions, which gave participants a chance to share their perspectives, reflect with other leaders from their cities and together gain deeper insight. Each presentation concluded with questions for leaders to digest what they are hearing and how it applies to the unique ministry environment in their cities.

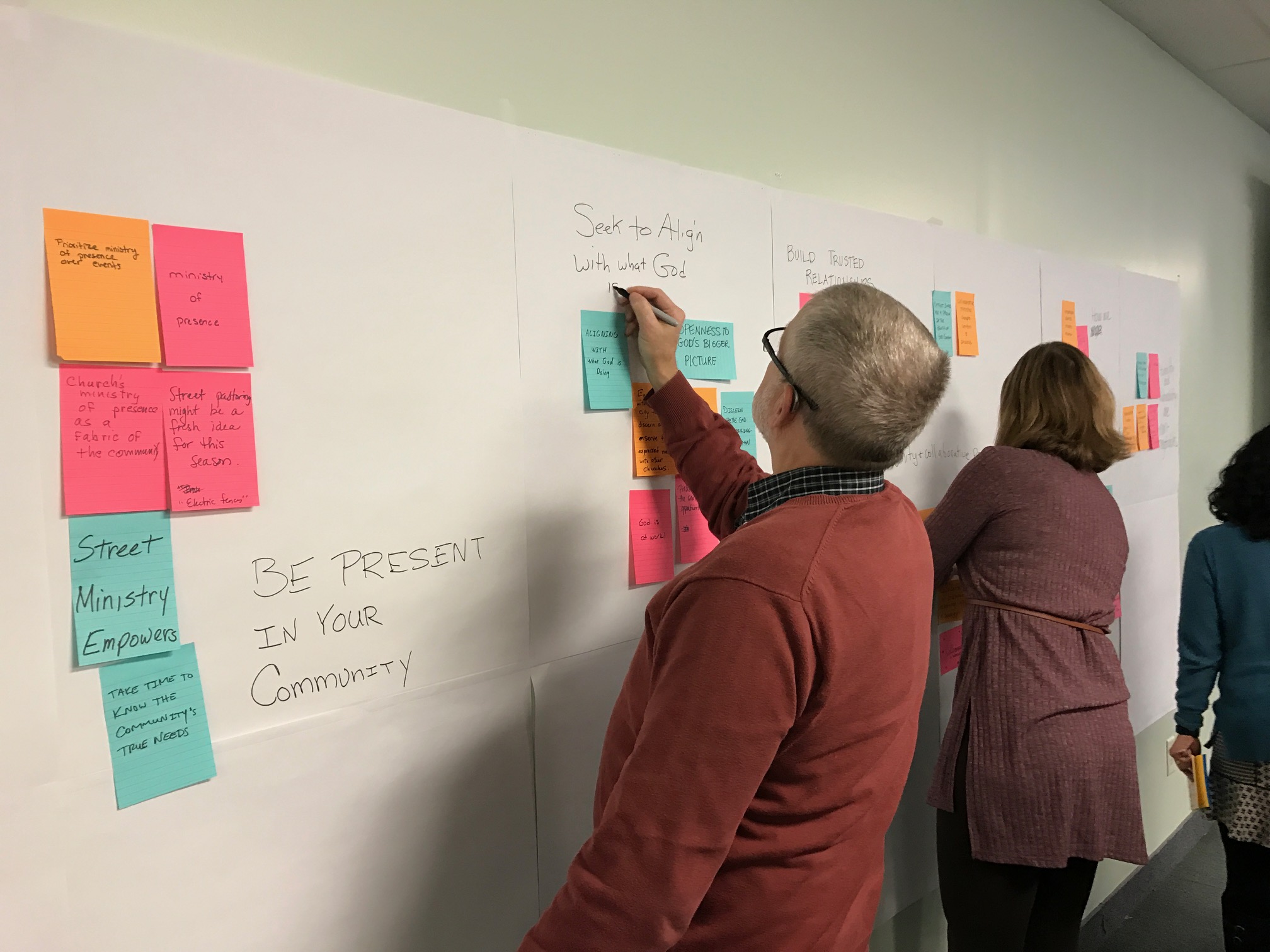

In the last part of the day, participants engaged in a large-group processing and sharing exercise to determine the key learnings that were emerging throughout all the cities. Through "flash hexagoning," individuals responded to the question “What have you learned today?” on sticky notes, and then shared these with their table. The table then grouped responses by common themes and chose up to three overarching key learnings to be highlighted for the entire room. Each table's key learnings were written on larger sticky notes, which were then themed on the wall by the large group. Ten key insights emerged, which we used to focus our concluding prayer time for God’s continuing gospel movement throughout New England.

The ten key principles from the forum are stated below, with select, undergirding sticky notes in quotes and additional insights from day-long notetaking at the tables.

LARGE-GROUP LEARNINGS

1. Unified prayer is essential

Praying together is the foundation of a gospel movement, and "precedes an environment of collaboration and love." "Commnunity-based prayer launches community action." It is no surprise that many of the cities with strong Gospel witness also had a strong inter-church prayer network across denominations. Truly, we can’t expect the Holy Spirit to move in our cities without unified prayer.

2. Leadership and structure is required

"Effective moments require engaged and available leadership." "A structure is needed to capture and accelerate partnerships." Pastors are often the gate-keepers for collaboration; if they don’t know other pastors, then churches won’t work together. "Training of pastors/leaders" is key. At the same time, we need to restructure the current church system so these initiatives are not entirely placed on the pastor. There is much momentum around training congregation members working in secular fields to disciple people in their occupations to further the kingdom of God. To this end, pastors in Hartford have been discussing a Kingdom in the Workplace conference to help people network across churches vocationally.

3. Know your community

Needs within cities are ever-changing: we must become multidimensional in our thinking and approaches to serve our communities. Initiatives should be birthed through the assets and needs in the community, so that ministry is transformational rather than transactional. "Understanding demographics for Gospel impact" by tuning into the "kairos opportunities" presented by who is in or coming to a city--through immigration, refugee resettlement, etc. There is a lot of momentum throughout New England around refugee ministries, and God is bringing us an opportunity to engage the nations through the refugees among us.

4. Be present in your community

A "ministry of presence" is key, and upon this foundation events can be leveraged--we must "prioritize presence over events." Church leaders are continually seeking to find a good balance between initiating collaborative events and adopting a consistent ministry of presence-- a dynamic that plays out not just when a church engages the community, but also when churches engage each other. All of the great gospel movements are happening outside the four walls of the church. Leaders in Portland have found that the less church-centric and the more sent out into the neighbors a church can be, the better.

5. Seek to align with what God is doing

Rather than just starting new things, leaders should find things that are already happening and join in, asking “How can we be a part of this?” This curious, open, discovery-oriented approach identifies and celebrates where "God is at work," and enables us to see our ministry within God’s bigger picture.

6. Build trusted relationships

Leaders across New England continually attribute gospel movement to strong, trusting relationships between leaders. God speaks to many people at once - we can only discern what God is doing by being in relationship with one another. Developing authentic relationships that cross traditional boundaries and divisions is also key, but taking time to build trust cuts against our natural proclivity for “productivity.” However, trust-filled relationships make #7 (below) possible, and are also the basis of #8.

7. Unity and collaborative partnerships are needed to tackle complex problems

At least nine cities honed in on the importance of collaboration: collaboration is not just an optional goal for ministry, it is essential for united and effective gospel witness. Cities are complex, and churches miss major opportunities when they do not see secular/governmental organizations as potential allies, rather than obstacles. Boston has seen the incredible value of intentional partnership between churches, community organizations, and social service agencies within small geographic regions of the city. In Portland, church leaders have come together to serve the refugee population and address the drug crisis, complex situations that are too big for any one church to tackle. Leaders in Worcester describe the need for some kind of clearinghouse that brings us together and helps to coordinate our prayer, witness, and service.

8. Intentional diverse leadership is needed

Churches and ministry efforts are richer when they are diverse because more diversity equals more lenses, resulting in a clearer vision. We need to get outside our cultural and denominational bubbles in order to gain insight on our own stereotypes and biases, so we can see God and others more clearly, as well as our part in what He is doing. Pursuing diversity in any context (church, leadership, collaboration) needs to be intentional and it is not going to happen naturally. Churches in Cambridge have found that diversity is built through food, friendship, and giving voice to people at the table. Who is at the table when something starts often means that the starter group ends up being the decision-makers, so having multiple entry points where new people at the table can co-create, not just "follow," makes functional diversity more likely.

9. We need to engage hard conversations

"Comfort zones are a prison in the growth of God's Kingdom." Therefore we have to break outside of our comfort zones and pursue hard, vulnerable conversations with those who are different from us, but this isn’t easy. Working together "disrumpts comfort and process" and we need to anticipate that and press through. Our "unconscious mental models"-- how we think the world is or how it works-- really matter, and these can be challenged when we work together. Even with the best intentions, sometimes we can operate counterproductively (for example, through "toxic charity"), and our willingness to engage in hard conversations will determine whether these blindspots can be addressed. One of the biggest challenges is for churches to create collective long-term change, rather than the tendency to follow the “flavor of the month.”

10. Humility and vulnerability are non-negotiables

We must "learn to communicate with a humble posture." "Humble, honest relationships must be prioritized." Like Jesus, we must have the attitude that we came not to be served, but to serve. Our humble approach is something that should stand out about the Christian Church and as we engage one another. Looking through the lens of our own need/brokenness opens us up to better understand and come alongside others; this shifts how we reach out and understand ministry. In many cases, when partnerships are empowering the community and the local leadership so that they are leading locally, the Church may not get the immediate credit. (Good thing we have an audience of One.)

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

Through reflecting and dreaming together, and through fellowship and prayer, a vision for growing the Kingdom of God in New England was expanded and strengthened. Here are some comments from participants:

“I was surprised that God’s work in New England is fairly common from city to city. The same “city issues” exist everywhere!”

“Today, I learned the value of accessing as many lenses to view my city as possible, and that building relationships across our differences is worth whatever it costs.”

“I learned about the need for diversity to be present in our dialogues.”

“It was inspiring to see what God is doing in our region.”

“It was cool to see how prayer and John 17 unity is resonating throughout the region.”

“The flash hexagon activity was a great way to digest the information, and made me think about the art of God’s refracted light.”

“I learned about the importance of fostering united prayer and authentic relationships with others outside of my normal silos.”

“I was encouraged to see that there are many in my city who have a heart to come together and see God do a good work!”

NEXT STEPS:

New London: Leaders in New London were encouraged by Worcester’s model of two churches collaborating to run a sober house together and are exploring implementing this in New London. They are also considering starting a free arts and crafts in the park once/week during the summer.

Rhode Island: Based on the New England City Forum conversations, leaders in Rhode Island thinking about how to rebrand their movement towards the “Together” terminology, developing a sub-area strategy using the NH Alliance as a model, and continuing to develop the 24/7 prayer network.

Connecticut: CityServeeCT is now working to invite more than 100 additional pastors to their monthly meetings and rotate the meeting location between cities.

Maine: Leaders in Maine are considering implementing a street pastor’s ministry in Lewiston and how they can respond well to immigrants in Portland.

Hartford: A pastor's luncheon is taking place on March 30th to consider how to foster greater unity and relationship among diverse leaders in the Urban Alliance Network.

Worcester: In a follow-up meeting, Worcester church leaders discussed the need for their team to represent the full racial, ethnic, gender and denominational diversity of Worcester. They are also considering how to nurture better church/community collaboration through focused research, a street pastor's ministry, and local school partnerships.

Examples of Collaboration in the Greater Boston Church Community

There has been a rich history of ministry collaboration in the Greater Boston Christian community. This document gives a brief description of some of the significant ministry initiatives in urban Boston that involved a broad coalition of ministry partners, and/or involved significant partnering across sectors. Much more could be said about each of the ones listed, and many more initiatives, projects and ministries could be added to this list.

Compiled by the Emmanuel Gospel Center for Greater Things for Greater Boston Retreat October 8 – 10, 2017

There has been a rich history of ministry collaboration in the Greater Boston Christian community. This document gives a brief description of some of the significant ministry initiatives in urban Boston that involved a broad coalition of ministry partners, and/or involved significant partnering across sectors. Much more could be said about each of the ones listed, and many more initiatives, projects and ministries could be added to this list. Please send additions or other feedback to Jeff Bass (jbass@egc.org).

The 1857-1858 Prayer Revival spread to Boston when the Boston "Businessmen's Noon Prayer Meeting" started on March 8, 1858, at Old South Church (downtown). There was considerable doubt about whether it would succeed, but so many turned out that a great number could not get in. The daily prayer meetings were expanded to a number of other churches in Boston and other area cities. Wherever a prayer meeting was opened, the church would be full, even if it was as large as Park Street Church. While the revival was noted for drawing together businessmen, it also involved large numbers of women. For example, the prayer meetings of women at Park Street Church were full to overflowing with women standing everywhere they could to hear.

When Dwight L. Moody came to Boston in 1877, he led a cooperative evangelism effort among many churches. This three-month effort drew up to 7,000 people at a time to the South End auditorium for three services a day, five days a week. Moody encouraged a well-organized, interdenominational effort by 90 churches to do house-to-house religious visitation, especially among people who were poor. Two thousand people were spending a large part of their time in visitation, covering 65,000 of Boston’s 70,000 families. The home visitations served the practical needs of mothers and children as well as their spiritual needs. The Moody outreach also related to workers in their workplaces. Meetings were established for men in the dry-goods business, for men in the furniture trade, for men in the market, for men in the fish trade, for newspaper men, for all classes in the city.[1]

[1] These first two are from History of Revivalism in Boston by Rudy Mitchell; 50 pages of fascinating and inspiring reading. Use hyperlink or search at egc.org/blog.

One of the most important organizations in Boston for the healthy growth of the church has been Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston Campus, commonly known as CUME (the Center for Urban Ministerial Education). A short version of its interesting history is that it came about because of the joint hard work of leaders in the city (particularly Eldin Villafañe and Doug Hall) and leaders at the Seminary (particularly Trustee Michael Haynes, pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury). CUME officially opened with 30 students in September 1976 at Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury. CUME currently serves more than 500 students representing 39 denominations, 21 distinct nationalities, and 170 churches in Greater Boston. Classes are taught in English, Spanish, French Creole and Portuguese, with occasional classes in American Sign Language. (from GCTS website).

The Boston TenPoint Coalition was formed in 1992 when a diverse group of urban pastors was galvanized into action by violence erupting at a funeral for a murdered teen at Morning Star Baptist Church. Reaching beyond their differences, these clergy talked with youth, listened to them and learned about the social, economic, moral and ethical dilemmas trapping them and thousands of other high-risk youth in a cycle of violence and self-destructive behavior. In the process of listening and learning, the Ten-Point Plan was developed and the Boston TenPoint Coalition was born.

The “Boston Miracle” was a period in the late 1990s when Boston saw an unprecedented decline in youth violence, including a period of more than two years where there were zero teenage homicide victims in the city. Much has been written about The Boston Miracle (and a movie starring Matt Damon is in the works), but there are competing narratives about what caused the violence to decline. Certainly the work of Boston police, the Boston TenPoint Coalition, Operation Ceasefire, and supporting prayer all played major roles.

In response to the first Bush administration’s faith-based initiative in the early 1990s, a group of funders (led by the Barr and Hyams foundations) brought together leaders from the Black Ministerial Alliance (BMA), Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC), Boston TenPoint Coalition, and the United Way to respond to a Federal request for proposals. Out of this conversation, the Boston Capacity Tank was formed, and we were able to successfully secure a Federal grant ($2 million per year for three years, then funding from federal, state, local, private sources afterwards). The Tank was led with input from the founding partners, and built the capacity of more than 350 youth serving organizations over 10 years.

Victory Generation Out-of-School Time Program (VG) was created by the Black Ministerial Alliance in 1992 in response to the educational disparities documented between youth of color and their suburban counterparts. The BMA partnered with 10 churches to provide academic enrichment to students in the Boston Public Schools in order to improve their grades and test scores. Ninety-four percent (94%) of students consistently participating in VG were found to increase one full letter grade in achievement and, for those not at grade level, achieve grade level. Most remarkable is that although this is a church-centered program, upwards of 80% of the students attending VG are not members of any church.

In the 1990s, Vision New England hosted three-day prayer summits for male pastors that was attended by as many as 90 leaders. The goal was to focus purely on seeking God through prayer, worship and reading Scriptures with no speakers, only facilitators keeping things on track. They were not only well attended but powerful times that were blessed by the Holy Spirit. In 2000, leaders in Boston met to discuss holding a similar prayer summit that also would include female leaders in the Boston area. Thus began the Greater Boston Prayer Summit, which ran two-day prayer retreats for up to 75 pastors and ministry leaders in the spring, with a smaller one-day prayer gathering in the fall. The Summits were effective in connecting leaders around Greater Boston, and promoting unity in the church across various church streams. Energy for the Summit faded in recent years, and the planning team disbanded in 2016.

In the mid-1990s, there was a group of pastors and business leaders who met several times to talk about issues in the city and potential partnering. The business leaders challenged the city leaders to agree on an issue to address. “If the city leaders agree, resources will flow!” Partly in response to this challenge, EGC worked with a broad coalition of churches and youth leaders to start the Youth Ministry Development Project (YMDP). The goal, set by the coalition, was to see the Boston churches grow from only one full-time church-based youth worker to twenty over ten years, and to provide much better support for church-based youth work. Funding was provided primarily by secular foundations, and the YMDP project was well-funded and met its 10-year goals.

Boston Capacity Tank’s Oversight Committee (including funders and faith leaders) challenged itself to look at the systemic issues of youth violence in Boston. The Committee asked EGC to take the lead in forming the Youth Violence Systems Project (YVSP) that partnered with Barr, youth leaders in several key Boston neighborhoods, local organizations such as the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), the Boston TenPoint Coalition (to interview gang members), and a nationally known Systems Dynamics expert (Steve Peterson). The work influenced many leaders to take a more systemic view of their activities, and the project approach was published in a peer review journal.

In 1997, United Way of Massachusetts Bay (UWMB) collaborated with local faith leaders to initiate the Faith and Action (FAA) Initiative. UWMB had traditionally only worked with secular organizations. The Faith and Action Initiative was envisioned as funding faith-based programs for youth precisely because of their spiritual impact on participants. Churches—especially Black churches—in some hard-to-reach Boston neighborhoods were serving youth in a way that more traditional agencies were not. FAA would direct small grants to these religious organizations on a trial basis. No grant recipient would be allowed to proselytize. But each would be required to include spiritual transformation in its program as a condition of winning a grant (from Duke case study on FAA).

The Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (GBIO) is an organization of 50 religious congregations and other local institutions that joined together in 1998 in order to more powerfully pursue justice in Massachusetts. Since its founding, GBIO has played a critical role in securing Massachusetts health care reform; helping to roll over $300 million into the construction of affordable housing in the state; and supporting local leadership in efforts to attain worker protections, school renovations, adequate access to school textbooks, as well as other major victories (from GBIO.org).

The Institute for Pastoral Excellence (IEP) was planned and implemented in 2002 as an initiative of the Fellowship of Hispanic Pastors of New England (COPAHNI). COPAHNI is a regional fellowship of Hispanic churches and ministries. The purpose of IEP was to help Hispanic pastors and lay leaders in New England build their foundation for effective and resilient ministry. IEP was funded with two multi-year grants from the Lilly Endowment ($660,000 and $330,000, respectively). IEP maintained strong partnerships with Emmanuel Gospel Center (fiscal agent, consulting, and administrative support) and the Center for Urban Ministerial Education and Vision New England (consulting, speakers, and materials).

In 2004, a group of suburban leaders met with urban leaders to see if we could provide resources so connecting would be easier. “The answer can’t be that you have to talk with Ray Hammond to get connected.” Out of those conversations, CityServe was born. The goal was to create online resources for connecting, coupled with staff support for the process. Harry Howell, president of Leadership Foundations, offered to donate a couple days a week to get this off the ground, and EGC raised some funds and hired a staff person to get things started. Harry, however, had a heart attack and was not able to follow through on his commitment, the project never found its footing in the community or with donors, and the experiment ended in 2007.

In 2004 and 2005 there was a growing sense among many believers that God was about to move powerfully in the New England region. Covenant for New England was formed to promote the functional unity, spiritual vitality, and corporate mindset that would prepare the way for a fresh movement of God’s Spirit. In 2006, Roberto Miranda, Jeff Marks, and others involved inCovenant for New England met with British prayer leader Brian Mills to discuss how to broaden the Covenant network to include all of New England. In February of 2007, the New England Alliance was formed consisting of representatives from all 6 New England states. This group began meeting monthly in various places around the region. One unique aspect of Alliance gatherings was they always began with an hour or two of prayer before any other business was brought up for discussion.

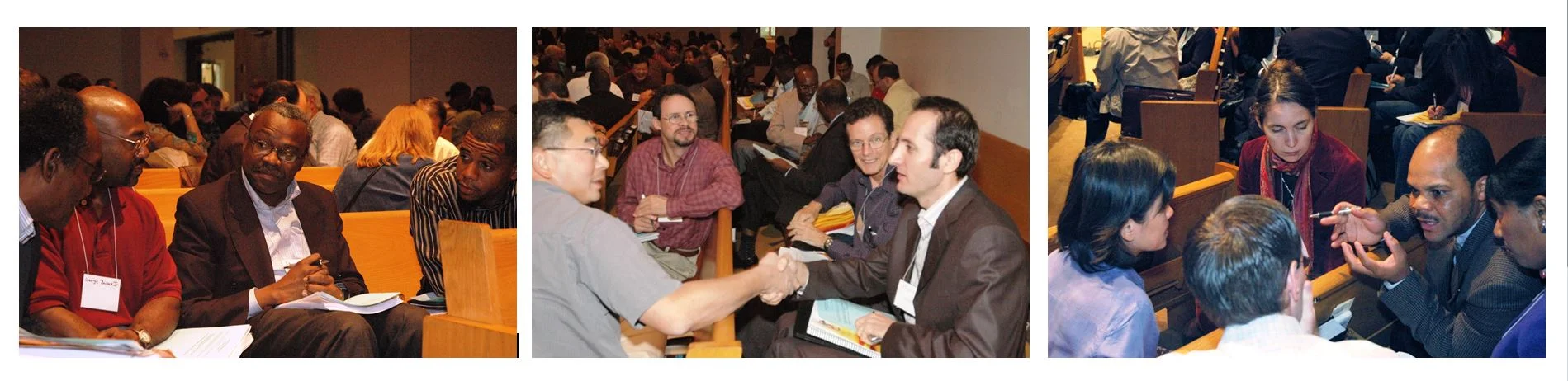

From 2008 to 2010, a multi-ethnic group of urban and suburban church leaders worked together to plan and prepare for the national Ethnic America Network Summit, “A City Without Walls.” The conference was jointly hosted in April 2010 by Jubilee Christian Church International and Morning Star Baptist Church. The Summit featured local speakers (including Dr. Alvin Padilla of CUME and Pastor Jeanette Yep of Grace Chapel) and national speakers with deep Boston roots (including Rev. Dr. Soong-Chan Rah). The Summit brought together many diverse partners and established relationships that last today.

In 2010, Boston Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Carol Johnson created a community liaison position to foster more school partnerships with faith-based and community-based organizations. The opportunity for church/school partnerships led to some significant urban/suburban church partnerships, such as Peoples Baptist/North River, and Global Ministries/Grace Chapel. EGC’s Boston Education Collaborative currently supports about 40 church/school partnerships in Boston.

Greater Things for Greater Boston grew out of the initial desire of several key urban and suburban pastors to see broader connections between pastors and churches in Greater Boston. Central to developing the vision were biennial “Conversations on the Work of God in New England” which highlighted local and national pastors and networks joining with God to do innovative work to reach their city. The first conversation was held in May 2010. Topics have included “Why Cities Matter?”, church/school partnerships, community trauma, and much more. The identity and mission of GTGB is: “We are a diverse network of missional leaders stubbornly committed to one another and to accelerating Christ’s work in Greater Boston.”

There were at least two precursors to Greater Things for Greater Boston. The Boston Vision Group formed in 2001 “to see in the next 5 – 10 years, Boston will be a place where there is infectious Christian Community wherever you turn.” The Greater Boston Social Justice Network, formed in 2004, was “committed to eradicating social injustices that impede the advancement of God’s kingdom on earth.” Both groups included a variety of urban and suburban leaders, and both were active over several years.

In January 2017, EGC and the BMA worked with Jamie Bush and Drake Richey to convene a group of mostly professional under-40s, in the financial district, to consider what God has been doing in Boston over the last 30 years. This led to another meeting of the same group in March to hear from Pastors Ray Hammond and Bryan Wilkerson about what the Bible says about engaging your talents and the needs of society, with small-group discussion, pizza and wine. In May, the group met again at the Dorchester Brewing Company for a discussion of seeking God's purpose for your life and prayer. Again with food (and, of course, beer). Next steps, including hopefully meeting for prayer, are being considered.

The Chinese Church in Greater Boston

From just two Chinese churches in greater Boston 50 years ago, the number has grown to more than 25 congregations serving an expanding Chinese population. The growth of the Chinese church in and around the Boston area is something to celebrate. Its strength and integrity, and the quality of its network—unified for prayer, for youth and college ministry, and for international missions—stand as a model for other immigrant and indigenous church systems.

The Chinese Church in Greater Boston

by Dan Johnson, Ph.D., and Kaye Cook, Ph.D., with Rev. T. K. Chuang, Ph.D.

From just two Chinese churches in greater Boston 50 years ago, the number has grown to more than 25 congregations serving an expanding Chinese population. The growth of the Chinese church in and around the Boston area is something to celebrate. Its strength and integrity, and the quality of its network—unified for prayer, for youth and college ministry, and for international missions, among others—stand as a model for other immigrant churches and indeed for other indigenous churches as well.

What does the Chinese church in Boston look like? What are the strengths and weaknesses as well as the clear opportunities and threats that face these churches at the start of the 21st century?

Students and immigration

In 2016, as many as 350,000 students and visiting scholars from China were actively working in the U.S., a population that dwarfed the number who came from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Over 30% of all international students studying in the U.S. are from China, according to the Institute of International Education (www.iie.org). Not surprisingly, thousands of these are regularly drawn toward Boston-area colleges and universities, as well as to the opportunities available to them in the region’s “knowledge economy.” The 2010 U.S. Census found that the Chinese population of the greater Boston area numbered nearly 123,000, some two and one-half times as many as were present just 20 years before.

Of these, it is estimated somewhere between 5% and 8% identify as Christian. Many of the Chinese newcomers to the area each year are already Christian when they arrive, in which case the Chinese church provides them a primary community to ease the transition to life in a new place. The others are generally quite open to the Christian message. Indeed, to this day Chinese students are routinely found to be the most receptive group to Christian outreach efforts on local campuses. As a consequence, this influx of new immigrants and students from China has brought significant numeric growth to the Chinese church over the last 25 years. Most notably, most of the established Mandarin-speaking congregations experienced 20-80% growth over the decade of the 1990s. Such growth has generally plateaued since then, but new church plants have continued apace.

Church planting

Chinese Church of Greater Boston

Since 1990, more than fifteen new Chinese churches have been planted, mostly Mandarin-speaking, and mostly serving small, geographically distinct communities and congregations. From a mere two Chinese churches in the entire region 50 years ago, today the Chinese church in the greater Boston area includes more than 25 separate congregations. The steady stream of newcomers from mainland China has also reshaped the character of the Chinese church in the region. The most obvious change is the shift from predominantly Cantonese-speaking congregations to predominantly Mandarin-speaking ones.

As noted, most Chinese church plants over the last 25 years have been established to serve newly settled Mandarin-speaking communities. In a few other instances, older churches that originally served Cantonese-speakers have seen their ministries to the Mandarin-speaking community expand dramatically while their Cantonese populations have dwindled or disappeared altogether. This transformation is more than just linguistic in nature. The Mandarin-speaking newcomers from mainland China are mostly first-generation Christians and new converts. Their formative experiences were generally in a more materialist, atheistic culture, and they often identify primarily with the values and orientations of the academic and professional cultures in which they are immersed. This general lack of church experience has made basic biblical education and discipleship a more pressing need in the congregations that serve them. The fact that very few are ready to step into leadership and ministry roles in the church also creates a gulf between the new generation of Chinese Christians and the established church leadership. By virtue of their formal theological training, deep spiritual commitments, and long habituation in the relatively more developed Christian communities of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the United States, church leaders in Boston’s Chinese communities often find it harder to connect with the felt needs and mentality of their newest congregants. The challenge is made even more difficult by the fact that many of Boston’s second-generation Chinese Christians, who might otherwise be there to welcome these newcomers into the Chinese church, have chosen instead to become members of American or Asian-American churches.

These social dynamics provide the backdrop for the analysis that follows of the current state of the Chinese Christian church in the greater Boston area. Beyond its identifiable strengths and weaknesses, and the clear opportunities and threats that it faces, is the simple realization that this is a seventy-year-old church undergoing a significant growth-induced transformation.

STRENGTHS

Interchurch collaboration

One of the greatest strengths of the Chinese church in the Boston area is that the various churches that comprise it mostly get along and have forged important collaborative relationships. The largely non-denominational character of the churches has minimized theological frictions between them, and the numerous personal ties between individuals across congregations—often forged in common spaces, such as the Boston Chinese Bible Study Group at MIT—help to smooth inter-congregational relationships more generally. The collaborative efforts that have resulted include regular prayer gatherings, shared missions programs, joint sponsorship of career missionaries, evangelistic meetings, and a gospel camp. Such programs are often initiated and organized by individual churches and then opened up to other area churches, as the Chinese Bible Church of Greater Boston (Lexington) did for many years with its annual gospel camp. The fact that even the largest churches in the community (including the Boston Chinese Evangelical Church and CBCGB) have been willing to sponsor and participate in such joint efforts has gone a long way toward ensuring their success.

Cultural centers

The Chinese church also serves as a primary reference group for many newcomers to the area, as they have become some of the most active and well-organized social institutions within the Chinese community. Many new immigrants naturally turn to the church for help. The familiar language, cultural references, and social structures they encounter in the church are key factors in securing their sense of identity when all else around them is unsettled. The larger churches’ programs for children and youth also attract immigrant families.

An ethic of evangelism

Another strength of the Chinese church in the area is the ethic of active evangelism that has long been cultivated in its constituent congregations. For many years, this ethic has animated large-scale, seeker sensitive programs that have encouraged and enabled church members to put it into practice, aggressively evangelizing their kinspeople. Many of these programs—such as the CBCGB’s annual gospel camp—have since disappeared, and it remains an open question whether the evangelistic focus of the church can be sustained in their absence. Nonetheless, the inspiring heritage of evangelistic activity is itself a strength of the Chinese church in and around Boston.

A place for Mandarin-speaking immigrants

Lastly, the very fact that so many Chinese churches in the area were either founded to serve Mandarin speakers or have since developed vibrant ministries for the Mandarin community is a significant strength. Not every Chinese community around the world is so prepared to welcome and minister to the steady stream of Chinese immigrants from the mainland that inundates them today. The Boston area’s dense network of Mandarin-speaking churches marked by an intellectual richness and a strong professional class leaves it well positioned to meet the needs of the future church in Boston.

WEAKNESSES

Cultural Isolation

Historically, a lack of interaction with people who are not Chinese has probably been the most significant weakness in the Chinese church in and around Boston. The founding members of the most established churches have minimal contact, if any, with the non-Chinese community. Moreover, Chinese churches have rarely tried to hold joint events with other groups, with CBCGB being the one noteworthy exception. Such isolation from the surrounding society has been an obvious problem for the further development of the Chinese churches. This problem has abated somewhat, however, with the infusion of a larger professional class into the church over the last 25 years. This population generally has stronger ties to the secular professional networks in which they are immersed than to the ethnically-rooted churches they happen to attend.

Yet with this more worldly orientation comes the other problem of a widespread shallowness in the understanding of and commitment to the historic Christian faith. The church is in dire need of addressing this problem through basic Christian education and discipleship.

The generational divide

Another weakness besetting the established Chinese church is the deepening of the generational divides that separate older from younger Christians, first-generation immigrants from second-generation, and so on. While such divides have always been present, in recent years they have grown in ways that lead to the exodus from the Chinese church of those who were brought up in it. As noted, many of those who leave find their way to American churches that seem to address their needs more effectively. Many others, however, end up leaving the church altogether.

Small churches

Lastly, the problem of small congregational sizes hampered by resource constraints remains as prevalent today as ever. While the explosive growth of the last 25 years clearly benefited a handful of churches, the emergence of smaller congregations with an emphasis on ministry to their particular local communities has left many vulnerable. More than half of the Chinese congregations have less than 100 attendees, and these struggle financially with limited personnel. Many of them face such problems as a lack of volunteer workers, limited or no youth and children’s programs, and the difficulty of reaching a minimum threshold size to sustain growth. For some, it is challenging enough to remain viable. In this respect, a revival of the spirit of collaboration among the Chinese churches, with conscientious participation by the larger churches in the area, may be a key to the continued survival of these vital congregations.

OPPORTUNITY

Immigration continues

The steady and deepening stream of Chinese immigration from the mainland shows no signs of slowing in the coming years. The educational environment and the high-tech job market in the area will continue to attract many, providing an ongoing inflow of immigrants. Some of these newcomers are eager to attend a church, but many are not. Given the numbers, the proliferation of Chinese churches over the last few decades may continue, but careful observation and strategic planning will be needed to identify emerging pockets of Chinese newcomers who could be well served by a local Chinese church.

Changing cultures and thought systems

The arrival of more recent groups of graduate school students, scholars, and other professionals pose new challenges based on their distinctive generational experience and worldview. The factors that led many Chinese radicals of an earlier generation to explore and embrace Christianity—namely, the simple impulse to distance oneself from Maoism and communism, or the desire to secure an identity and existential anchor by identifying with “Western” institutions and thought systems, or even the hope of getting ahead in the modern world by adopting ways of thinking that are more prevalent outside China—have all been undermined in various ways.

The Chinese immigrants of today have grown up in a consumerist society that understands itself to have arrived, fully modern and ready to conquer the world. To the extent that such a mindset generates less of a felt need to turn to God, we might expect the boom in Chinese conversions to Christianity in the years following the Cultural Revolution and the massacre in Tienanmen Square will slow. Yet the Chinese church should seize it as an opportunity to develop new ways of sharing the Gospel so that it will be heard by those who have new ears.

Collaborative missions and outreach