BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Hidden Treasures: Celebrating Ministries to the Nations

A practical guide to encourage, inspire, and inform churches how to organize and plan an intercultural ministry event in their city.

Hidden Treasures: Celebrating Ministries to the Nations

A Manual for Organizing and Planning An Event in Your City

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 90 — June 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor

The vitality of the church in Boston and New England is connected to vital expressions of the church around the world through hidden relational networks and ministries. Discovering and nurturing the development of these networks, ministries, and their leaders helps nurture the growth of the church broadly and locally. Although often unnoticed or undervalued, these leaders and their ministries are specially gifted and effective in reaching unreached people groups in Boston and back in their homelands. Their proximity and presence also provides the opportunity to develop and experience a more culturally diverse expression of the church that includes people from every tongue, tribe, and nation. Because of this, these leaders are a treasure in our city and in God’s Kingdom that need to be recognized and celebrated.

With this in mind, Intercultural Ministries of the Emmanuel Gospel Center equips churches and ministries to embrace their multicultural future and helps them navigate crosscultural challenges and opportunities. They network, train, and consult with churches and organizations that want to promote effective intercultural ministry. The Hidden Treasures event in August 2012 was designed to bring awareness to effective diaspora ministries in New England; build and strengthen intercultural ministry relationships that honor God and provide greater capacity for doing collaborative Kingdom work; identify potential partners, volunteers, and interns for their respective ministries; and raise funds for the participating partners/beneficiaries.

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries, and Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director, created this manual to tell the story of the event, share what was learned, and provide a practical guide to encourage, inspire, and inform churches how to do the same.

1. Jeb Shaker (l.) with Paul Biswas (r.), 2. PoSan Ung, and 3. Torli Krua. (Rod Harris photos.)

Contents:

Introduction

Context for Hidden Treasures of the Kingdom Uncovered

The Hidden Treasures Event – a Pilot Project

Building an Intercultural Ministry Team – Reflection on Hidden Treasures’ Team Development

Practical Steps for Organizing a Hidden Treasures Event

Conclusion

1: Introduction

This Hidden Treasures Manual is a tool for churches interested in working with diaspora* leaders and connecting them to the wider body of Christ in their region. It aims to help you develop and organize an event in order to raise awareness for and celebrate what God is doing among diaspora populations in your neighborhood. Such an event provides a great opportunity for you to connect and build partnerships as well as to explore mission and outreach opportunities.

The idea for this manual emerged after the event “Hidden Treasures of the Kingdom Uncovered – Celebrating Ministries to the Nations in our New England Neighborhoods” took place on August 25, 2012, in Greater Boston. Intercultural Ministries of EGC was asked by other ministry leaders to coach them in developing a similar event in their cities.

Following this introduction in Section 1, the manual’s four main parts are these: Section 2 describes the context of the event, followed by a glimpse of our experience of the actual event in Section 3. As building a functional team is critical to Hidden Treasures, in Section 4 we use our experience of Hidden Treasures to reflect on aspects of building an intercultural ministry team. And in Section 5, we offer practical steps for people whose intent is to organize a similar event. We end with a brief conclusion in Section 6.

We hope our reflection and experience inspire and assist you and other churches and ministries to initiate similar events.

*The Greek word diaspora is found throughout the New Testament and is used to describe scattered or displaced people. We use the term to describe any first-generation people who have left their original homeland either by force or by choice. As such, it is an umbrella term referring to refugees, immigrants, and internationals. The term is increasingly being used in sociological and popular literature, for example, the African diaspora, the Asian diaspora, etc.

2: Context for Hidden Treasures of the Kingdom

The face of the United States of America is changing and diversifying. Although it is diversifying religiously, the majority of immigrants are Christians.* Through immigration and globalization, God has brought wonderful diaspora leaders/ministries to our country. These leaders have effective ministries and are passionate to reach their cities and the nations for Christ. The tremendous asset of diaspora leaders is having direct access and trust to minister to their own ethnic group, some of whom belong to “unreached” people groups. Because of a shared immigration experience, it is easier for these diaspora leaders to build relationships and trust with members of other ethnic groups than Euro-American Christians would be able to.

There is much potential in these ministries; however, many are under-resourced and isolated. Due to sociological marginalization, as well as cultural and language barriers, they find it difficult to present their ministries to other potential partners (churches, organizations and individuals). These diaspora leaders and their ministries are like “Hidden Treasures” among us. As they are such a spiritual enrichment and resource to New England as well as other regions in the U.S., Intercultural Ministries of EGC seeks to uncover these treasures and connect them to the wider body of Christ. Emerging from this desire, the idea of the 2012 Hidden Treasures event was born. Its goal was to celebrate these leaders and their ministries by being an advocate and creating space for relationship building, partnership development, and fundraising.

Our goals for this event were to:

Bring awareness to effective diaspora ministries in New England,

Build and strengthen intercultural ministry relationships that honor God and provide greater capacity for doing collaborative Kingdom work,

Identify potential partners, volunteers, interns for their respective ministries, and

Raise funds for the participating partners/beneficiaries.

*R. Stephen Warner, “Coming to America – Immigrants and the faith they bring,” Christian Century, February 10, 2004, 20.

3: The Hidden Treasures Event – a Pilot Project

On August 25, 2012, 160 guests came together at North Shore Assembly of God Church to celebrate ministries to the nations in New England.

As the focus of the evening was the diaspora leaders and their ministries, we will introduce them before we describe the development of the evening.

Young Africa/Universal Human Rights International. Rev. Torli Krua is a Christian leader who came to the U.S. as a refugee from his war-torn country of Liberia. Torli has started a small African congregation the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston and serves the wider African community in many ways, including advocating for an urban community vegetable garden for the poor to grow produce as a means of basic sustenance. Moreover, he is involved in initiatives of service and advocacy of justice for African refugees. Torli also serves as a catalyst for Christian community development in his home country of Liberia.

South Asian Ministries of New England. Pastor Paul Biswas comes from a Hindu background in Bangladesh. After becoming a Christian he was involved on many levels of national leadership in the Church in Bangladesh. Since coming to the Boston area, Pastor Paul has started several Bengali and South Asian house churches in New England to reach out to South Asian Muslims and Hindus. Moreover, Pastor Paul’s vision and passion is to equip and partner with other churches in reaching out to their South Asian neighbors.

Living Fields: Cambodian Ministries International. Pastor PoSan Ung is a survivor of the Killing Fields of Cambodia. He planted a church among the Cambodian population in Lynn, MA. He also serves as the director of Cambodian Ministries International at EGC. In this role, Pastor PoSan is serving the Cambodian Christian community across New England in leadership and ministry development. Moreover, Pastor PoSan is a valuable resource to the existing Church in New England in reaching out to Buddhist peoples. Pastor PoSan is also involved in Christian leadership development in Cambodia.

Compassion Immigration Ministry. Marlane Codair, a certified paralegal with years of experience in serving the immigrant/refugee community in Greater Boston, founded a church-based and government-certified Compassion Immigration Ministry. She serves immigrants and refugees in the Greater Boston area with competent legal counsel to assist with immigration-related issues and practical assistance such as English classes. Marlane’s work benefits not only her local church and community, but especially it serves the wider Christian community in practical ways to serve diaspora people in our region.

Next, we will describe the flow of the Hidden Treasures event itself.

We opened our doors at 5:00 p.m. The first part of the evening was an informal time of mingling where people could visit the ministry displays. Each of the featured ministries had a ministry display, representing their work and sharing their needs and collaboration opportunities. During this arrival time, guests also had the opportunity to participate in the silent auction.* The guests could bid on a variety of items, many of which (such as scarves and purses) were handmade in the home country of the diaspora leaders. Ministry T-shirts, flags, and jewelry also were available.

Around 5:30 pm we officially welcomed everyone and opened the buffet with a prayer by a representative of the host church. The buffet was amazing as people brought traditional food from their home countries.

Around 6:15 pm we started with the main program. Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler (director of Intercultural Ministries) gave an introduction into the theological context of diaspora ministries. He emphasized that all throughout the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation, God always used the movement of people over the face of the earth as one of the major means to express and advance His Kingdom. In fact, there is a whole theology of diaspora movement from Abraham to the Old Testament exiles to the scattered saints in Acts to John the Revelator on the Isle of Patmos.

God has always used the movement of people for the purposes of His Kingdom, a reality which can be also seen today in New England. Emmanuel Gospel Center refers to the growth of churches from different ethnic backgrounds over the last four decades as the “Quiet Revival.” We call it “quiet” because a lot of people did not know it was happening but, in fact, hundreds of churches were started during this time period.**

After this brief introduction, it was time for our “Hidden Treasures” to share about their calling and ministry. We asked each diaspora leader to bring a group of people affiliated with their ministries to perform a piece of music or dance in between the presentations. After that, a person connected to the specific ministry introduced the leader, shared what he or she appreciated about the leader, and encouraged the audience to be generous in their giving. Each of the leaders shared seven minutes about their ministries.

After all the presentations were finished, Gregg Detwiler emphasized the importance of their ministries in advancing the Kingdom of God in New England and invited people to give generously. The envelopes and response cards were distributed to each table and then collected and placed in a sealed envelope (which was taken to EGC, which was handling the finances for the evening.) The program ended with some worship songs led by a worship team from the host church.

Subsequent to the program, there was a dessert buffet with time given for the guests to visit the ministry and silent auction tables again.

In summary, it was a wonderful evening of fellowship and celebration. It was great to learn about what God is already doing among the diaspora people and give him praise for that. We raised about $6,000 in total (which was divided evenly among the four featured ministry partners), and many connections across cultural lines were made. There was much ethnic and generational diversity. Moreover, around 25 different ministries and churches and 15 different denominations were represented.

*Silent auctions are auctions held without an auctioneer. The items are placed on a table with a description and a starting bid. People place their bids on sheets of paper instead. People either can bid with their names or with numbers they receive at the registration.

**For a discussion of what is meant by the Quiet Revival, see this blog.

4: Building an Intercultural Ministry Team – Reflection on Hidden Treasures’ Team Development

In this section, we will describe the composition of our 2012 Hidden Treasures Team, as well as reflect on the process of building an intercultural ministries team that is capable of doing a project like Hidden Treasures.

We use the term “intercultural” rather than “multicultural” because we feel it better conveys the values of mutuality, interrelatedness, and interdependence.

Our 2012 Hidden Treasures core team was comprised of seven members. By nature of the project, our team was inherently diverse, comprised of:

A 60-year old Liberian male

A 40-year old Cambodian male

A 55-year old white female

A 58-year old Bangladeshi male

A 34-year old German female

A 52-year old white male

A 28-year old white female.

Team members were also diverse in variety of other ways, including diversity in ministry roles and in their relationship to diaspora people.

Three are ordained pastors, serving diaspora populations; one is ordained but not pastoring; five are leading organizations/programs they founded, all serving diaspora populations; and one is a student on a culturally diverse urban campus.

Two came to the U.S. as refugees, one as an immigrant, one as an international Christian worker.

Four were born in countries outside of the U.S., three in the U.S.

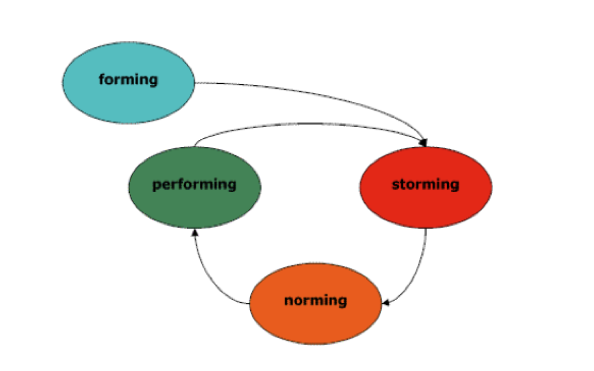

Next, we will explore important aspects of building a healthy intercultural ministry team, including a description of how we built our team. Bruce Tuckman’s classic “developmental sequence of small groups” is a helpful framework to describe the process. Tuckman describes five stages of developing a team: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning. Forming is when a new group convenes and is oriented toward achieving a particular task. Storming is the next stage and often involves intragroup conflict and resistance to group influence and task requirements. Norming occurs when in-group openness, cohesiveness and alignment develop, as well as the adoption of new standards and roles. Performing is the stage when group alignment and energy is channeled into creativity and constructive action. Adjourning is the final stage in the life cycle of a team when, due to the completion of a task or changes within the team, the team adjourns. In this final stage the main activity is self-reflection and group reflection.

Initially, Tuckman described four stages but in a subsequent 1977 article, Tuckman added a fifth termination stage, adjourning. The diagrams in this manual only reflect the first four. And while Tuckman first described these stages in a linear static manner, he subsequent began to envision these stages in a more dynamic cyclical manner. In our view, this cyclical version seems more consistent to the way things actually work in real life group development, and can be diagrammed in the following manner.

In this version of the model, the stages are not linear and relating to a point of time but cyclical and continuous. Members of the group continually seek to maintain a balance between accomplishing tasks and building interpersonal relationships in the group. We have found this balance to be a critical point to keep in mind: the process of building healthy relationships and a healthy team is equally important to the task, especially in intercultural teams.

Recognizing the all-pervasive ingredient of cultural diversity in team development may be demonstrated by adding a cultural backdrop (pink shaded area) to the model as follows:

This slight variation of the model illustrates how cultural diversity overlays the entire process of intercultural team development with cultural influences that add complexity to each of the elements of normal team development. Keeping these cultural influences in mind is critical in developing healthy intercultural teams.

To better understand how cultural differences affect team chemistry and functioning, consider a model of cultural orientation developed by Douglas and Judy Hall, called Primary and Secondary Culture Theory. Note the differences between the two cultural orientations.

| Primary Culture | Secondary Culture |

|---|---|

| 1. Relational need-satisfaction | 1. Economic need-satisfaction |

| 2. Extended family systems | 2. Nuclear or adaptive families |

| 3. Oral communication | 3. Written communication |

| 4. Informal learning | 4. Formal learning |

| 5. Spiritual explanations of reality | 5. Scientific, objective, cognitive explanations of reality |

In culturally diverse teams it is likely that each team member will be predominantly one or the other of these cultural orientations. For most of us, this will be determined by the dominant cultural orientation in which we were raised. Simplistically speaking, most first generation diaspora people identify as primary culture people while most middle- and upper-class Western-born people identify as secondary culture people. For intercultural ministry teams operating in the U.S., it is important to have team members from both of these cultural orientations, as each bring different strengths and weaknesses. (For more, see Doug Hall, Judy Hall, and Steve Daman, The Cat and the Toaster: Living System Ministry in a Technological Age, Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2010, p. 21.)

As we consider the contrasts noted in the table above, it is important to reflect on how people from each of these cultural orientations function and get their work done. Primary culture people rely more on oral communication than written communication and learn more through modeling than formal classroom settings. Secondary culture people tend to be the exact opposite. In primary culture, work gets done by relying heavily on relationships while in secondary culture work gets done by hiring people to do it. Understanding these cultural differences is part of the process of gaining the cultural competence necessary to creating healthy intercultural teams.

Note: Cultural Competence is a term that first appeared in human services literature in 1982 and has increasingly been used in fields of health care and, more recently, business. Cultural competence requires that organizations have a defined set of values and principles, and demonstrate behaviors, attitudes, policies and structures that enable them to work effectively cross-culturally. This includes having the capacity to (1) value diversity, (2) conduct self-assessment, (3) manage the dynamics of difference, (4) acquire and institutionalize cultural knowledge and (5) adapt to diversity and the cultural contexts of the communities they serve. It also means incorporating the above in all aspects of policy making, administration, practice, and service delivery, and systematically involve consumers, key stakeholders and communities. Adapted from: Terry Cross, Barbara Bazron, Karl Dennis, & Mareasa Issacs, Towards A Culturally Competent System of Care, Vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, 1989).

Having understood the cultural realities described above, it is not difficult to imagine the challenges and benefits associated with having a team comprised of people from both cultural orientations. In fact, it is precisely this reality—along with the challenges and benefits—that calls for an innovation like our Hidden Treasures project. Because we live in a rapidly changing and globalized world where primary and secondary culture people are increasingly intermingling, we must learn how to do ministry together in this new reality. And this learning must happen in multiple directions. Primary culture people must learn now to navigate in a dominant secondary culture, and secondary culture people must see and learn how to relate to primary culture people. Where these two cultures meet is a tremendous leverage point for Kingdom transformation, partnership, and growth, IF we learn how to build healthy intercultural teams and partnerships.

Tuckman’s stages of group development

Let’s now turn to describing and reflecting on the process we used in creating a functional intercultural ministry team to envision and implement our Hidden Treasures project, along with considerations for others who would like to create Hidden Treasures teams in their own communities. We will use Tuckman’s stages of group development to reflect on our process.

See Tuckman, Bruce W., 1965, “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups” Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399. This article was reprinted in Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal – Number 3, Spring 2001.

See also Bales, R. F., 1965, “The Equilibrium Problem in Small Groups” in A. P. Hare, E. F. Borgatta and R. F. Bales (eds.) Small Groups: Studies in Social Interaction, Knopf.

Forming. As noted above, our Hidden Treasures team was diverse by design, comprised of leaders from both primary and secondary cultural systems. Intercultural Ministries (IM) of Emmanuel Gospel Center was the initiator of the project and convened a group of diverse leaders to envision, plan, and implement the project. IM selected team members from a large pool of trusted diaspora leaders we have worked with in recent years. Each of the leaders selected has a proven and effective ministry, but also is under-resourced due to social and cultural separation within the wider body of Christ.

An important consideration for other ministry organizations that might wish to conduct a Hidden Treasures event is to take the time necessary to develop trusting relationships with all of the prospective Hidden Treasures partners. We have found that storytelling is an effective entry point for building this trust. Ideally, as in the case of our event in Boston, partners should be selected from known and trusted leaders.

Storytelling involves team members sharing portions of their life and ministry journey. Storytelling gives opportunity for team members to become vulnerable with one another and is a means for building a foundation for doing ministry together. Equally important to the actual storytelling is the skill of active listening from other team members. (Read more about the renewed interest in the role of storytelling within the Church by searching articles at Christianity Today magazine here.)

Storming. Storming is a normal and necessary part of team development. In team development among culturally diverse teams, storming is inevitable. Storming may result for any number of reasons: interpersonal conflicts, vision alignment, wrestling over defining roles on the team, and cultural misunderstandings. Teams must be prepared for and expect these types of storms.

On the other hand, it is important to note that these storms need not turn into a destructive hurricane! In the case of our Boston Hidden Treasures team, many of these storms were largely avoided because our team already knew one another and had a high degree of trust. Moreover, our team was comprised of leaders with a high degree of cultural competence skills and experience. The most significant storming we had was in the area of role expectations—helping team members to find roles according to their unique strengths—but even this was minimal.

Norming. Because of the aforementioned assets, the Boston Hidden Treasures team was able to come to vision alignment early in the process. The strengths of individual team members were harnessed and employed for the project. Roles were assigned with an awareness of each team member’s strengths and weaknesses, with a good blend of both primary and secondary cultural gifts. In our event, it was easy to see the strength of primary relationships among the diaspora leaders in that they were the most effective at recruiting people from their relational networks to participate.

Performing. When the norming process is done effectively, high performance in accomplishing the mission is a joyous fruit. Such was the case with the Boston Hidden Treasure event. This is not to say there were no glitches in the performance and execution of the event. There certainly were glitches, but they were minimal, mainly to do with “time” issues in the program, such as starting a bit late and underestimating the time it would take to serve food, etc. We sought to mitigate the potential time orientation conflict that is common among primary culture people (event-orientation) and secondary cultural people (clock-orientation) by asking all of our teammates—primary and secondary—to arrive to the event early and to plan each portion of the program with time limits in the forefront of our minds.

Adjourning. Adjourning is a part of every group’s life cycle, but it is important that as a group prepares to adjourn there is a season of reflection on both the past experience and future endeavors. Evaluation and reflection should not be viewed as a nice optional activity, but rather as a core value. In the case of the Boston Hidden Treasures team, we reflected on the event, our process as a team, and future considerations. Although our team adjourned, our team members continue to work with one another in myriad ways. In this manner, the Hidden Treasures process was a catalyst for building greater networks and capacity for working together. Moreover, team members are hopeful to see Hidden Treasure events multiplied in other cities and are committed to do what we can to see that occur.

The Importance of a Safe Learning Environment

One final point we would add about building an intercultural ministry team is the importance of a safe learning environment. Every healthy team – especially healthy intercultural teams – must nurture a safe learning environment to navigate the various stages of team development, to nurture strong relationships and to perform at a high level.

In order to move beyond superficial, polite relationships and to create a basis for hard questions, a safe learning environment is essential. Such a safe environment does not just happen, but needs to be created intentionally, which is not an easy undertaking. All our practical attempts need to be accompanied by prayer and the invitation of the Holy Spirit into the process.

Some of the practices and characteristics that help to create a safe learning environment are confidentiality, being a good listener, not judging one another but considering the best in one another, and being committed to one another’s growth. Moreover, it is important to not look down on those who confess their sins, temptations, or weaknesses. Focusing on our own issues rather than on others' is as important as avoiding ‘cross-talk’, which is being too quick to give unsolicited advice to others or trying to fix the other person.

On the other hand, being in a safe environment does not necessarily mean that we feel at ease and emotionally light. Therefore, it is good to know that a safe environment is not a pain-free environment, as growth is often painful. Additionally, it is not only about ‘me’ feeling safe, but also about helping ‘others’ to feel safe. It is not a place for expressing raw emotions without considering the effect this sharing will have on others. A truly safe environment welcomes different perspectives so it does not require a uniformity of opinion.

It is easy to describe what a safe environment is and what it is not, but how can we actually create a safe environment? The following diagram describes The Process of Creating & Reproducing a Safe Environment.

The original process diagram and article about ‘Developing Safe Environments for Learning and Transformation’ can be found in the Emmanuel Research Review, Issue No. 80 — July 2012, reprinted here.

The starting point for creating a safe environment is (1) willingness. It needs a community or organization that desires to create a safe environment. The next step is (2) skilled leadership to guide and nurture a safe environment. After that, (3) a group learning process has to take place to agree on and define qualities of a safe environment. A safe environment is not created once and will be there forever. It is very fragile and requires (4) skilled leadership that will model and maintain a safe environment. Moreover, a regular (5) reality check to assess the status quo is important. A community or organization can only progress if there is the willingness to be honest about where they are in the journey. This leads to the next step, (6) the continued practice through ‘action-reflection’ learning, and finally the hope is (7) reproduction, where members of the community or organization reproduce safe environments in their spheres of influence.

Building intercultural ministry teams that have the capacity to create and produce events such as Hidden Treasures is a critical need in our changing multicultural world. Healthy intercultural teams can serve as model for fostering intercultural ministry partnerships. Following the pattern described above can serve as a guide for developing such teams.

5: Practical Steps for Organizing a Hidden Treasures Event

Every event requires a lot of details to remember in order to have a smoothly run event. Before going into details, we want to emphasis that there is not one perfect way to organize such an event. A lot of flexibility is needed, especially in the context of intercultural events. There are different cultural approaches to items such as RSVPing or coordinating the food, but experience shows that everything comes together at the end, especially if there is strong relational basis.

Team. Before thinking about logistical details, the planning team needs to be formed and a host church or organization needs to be found. The planning team ideally consists of a project coordinator and assistant who lead the planning team, convene the meetings and connect the dots; the diaspora ministries leaders (no more than three per evening, ideally from three distinct people groups) who are the primary beneficiaries of the event; and a contact person from the host church who coordinates the logistics and communication with the host church. The diaspora leaders need to be selected carefully. In the case of the Hidden Treasures in Greater Boston, we chose the diaspora leaders with whom we had had had relationships for many years and knew that they were actively looking for more partnerships in the region. Besides following existing relationships, there are many creative ways to select the partners, such as selecting leaders from a specific geographical region or by a specific people they are serving or by a particular ministry such as serving the second generation or families.

As mentioned in the previous section, building a functional intercultural team is essential even though it requires more time investment. It is important that all team members own the event and have the same vision. Any sort of competition can be counterproductive for such an event. Besides the planning team, a team of volunteers to help during the event is also needed.

Each of the planning team members needs to take on one or more of the following areas of responsibility.

Host Church. It is critical to find a good host church that not only provides space, but also is a partner that is genuinely interested in diaspora ministry and willing to affirm leaders of different ethnic background within its own congregation. Ideally, a host church should take this project on as part of the expression of its vision, thus becoming a stakeholder and not just a provider of space.

The requirements for the host church would comprise following aspects:

To have one or two members of the congregation to serve on the planning team.

To raise up a diverse group of volunteers from the congregation to help in the event itself.

To donate the space for the event.

To help administer the logistics for the event.

To consider giving a donation toward the fundraising aspect of the event.

To promote the event among their folks to participate.

Depending on the relationships between the planning team and the host church, as well as its capacity, it might not be realistic that all these requirements are fulfilled.

Budget. One of the goals of the Hidden Treasures event is to raise support for the diaspora leaders and their ministry. Therefore, the expense should be kept as low as possible. For that reason we decided, for example, to have a potluck dinner.

Ideally, a sponsor can be found before the event to cover the expense of the event. The budget varies depending on the setting, the amount of in-kind donations, and how many people are expected. Our expenses added up to $425 with approximately 160 attendees including children.

There are two big areas of expense. First was the invitation, including printing flyers, reply cards, postage, envelopes and labels. The second area is the expenses related to the event itself, such as paper plates, cups, plastic ware, tablecloths, napkins, table or room decoration, tea, coffee and cold drinks. Moreover, it includes the printing of donation response cards and envelopes.

We had several volunteers who donated their professional skills, designing the invitation flyers and taking photographs.

Fundraising Aspects. As indicated above, one of the goals of the Hidden Treasures event is to raise support for the diaspora leaders and their ministries. In order to do it well, one non-profit organization or church needs to handle the finances. In some cases, such an organization will take administrative fees for the processing and bookkeeping. These costs need to be added to the expenses.

In order to raise funds, we had different strategies. First, we asked people for matching grants and sponsorships. Second, in the invitation we encouraged people to donate even if they were not able to come. Third, after the ministry presentations, we provided donation cards (to collect contact information) and asked people to contribute right then, in any amount they chose. We accepted cash, checks (made payable to the sponsoring organization) and credit cards. Each donor put his or her donation and donation card into an envelope that we provided and then sealed the envelope. Then these sealed envelopes were collected and put into a large manila envelope that was sealed and taken to the sponsoring organization for processing and receipting. And fourth, we had the silent auction. Winners were announced at the end of the evening, and each winner put his or her payment and response card into an envelope and sealed the envelope. The sealed envelopes with auction payments were put into a large manila envelope that was sealed and taken to the sponsoring organization.

After all expenses are deducted, the funds that were raised through donations to the freewill offering were divided equally among the ministries of the diaspora leaders.

For the silent auction, each ministry received the total of the winning bids for the items that ministry contributed.

Invitation/Marketing/Distribution. The major task before the event is mobilizing people to come to the event. Everyone on the planning team needs to use their contacts and relationships and intentionally invite people to the event. In order to invite people, flyers need to be designed and printed. Although it is more expensive and time intensive, it is important to send individualized invitation letters (including a response card and return envelope) to selected individuals or churches. Additionally, the event should be advertised through social media and email invitation to general mailing lists.

It is also helpful to create a website with further information about the diaspora ministries, an online donation option, as well as directions to the venue.

Evening Coordination. The evening coordination consists of three main parts: logistics, food/kitchen, and program. Ideally one person of the planning team is the champion for one of these areas and has a group of volunteers to assist.

Logistics. The logistics comprise setting up tables and chairs as well as decoration, making sure that all materials for the evening (such as donation cards, envelopes and program hand-outs) are produced and distributed, nametags are purchased, and so on.

Food/Kitchen. In case of a potluck dinner, all participants mobilize their networks and churches to contribute to the buffet. The food/kitchen team receives the food and makes sure things are kept warm or prepared adequately. Besides coordinating the food, this team needs to make sure there are enough plates, cups, silverware and napkins. They also need to prepare the cold and hot drinks and are responsible for cleaning up.

Program. Before the evening program starts, the program leader makes sure the welcome committee is instructed (although we asked people to RSVP, we chose not to have a registration list or preprinted name tags at the entrance), the sound/music equipment is set up, and all the people involved know the flow of the program and when they perform. Ideally, the program leader is also the MC throughout the program. See section two for the program flow.

Evaluation of the Event. As mentioned in section three, the final part of a team process related to a time-restricted project is adjourning well. Evaluation is a key element in such a process. A great method to evaluate a Hidden Treasures event is using the six thinking hats developed by Edward de Bono (de Bono, Edward, Six Thinking Hats, New York, Back Bay Books 2nd edition, 1999.) It basically helps to reflect on the event from different perspectives. Each hat has a different color and aspect to look at, as listed below. You certainly can expand the questions of each hat.

White Hat: “The facts, just the facts” - What were the basic facts about the event/ministry?

Yellow Hat: “Brightness & Optimism” - What were some of the most fruitful and positive things observed in the event/ministry?

Red Hat: “Express your emotions” - What “feelings” did you experience or observe?

Black Hat: “Critical thinking; Hard Experiences” - What were some of the distracting or disappointing or least fruitful aspects of this event/ministry? Were there elements that were missing that could have been helpful? Were there any things that felt particularly unproductive or even counterproductive? Where did we miss the mark?

Green Hat: “New Ideas, new possibilities” - What new concepts or new perceptions emerged in or through this event/ministry? What implications might these new understandings have on future ministry?

Blue Hat: “Next Steps” - What do you feel might be some “next steps” we need to move this process forward in a positive growing direction?

6: Conclusion

Overall, the Hidden Treasures event on August 25, 2012, was a wonderful time of fellowship and celebration with a diverse representative of the body of Christ. The evening was a tremendous blessing for the diaspora leaders as well as the participants. The greatest challenge we faced was not being able to effectively secure representative of Euro-American churches or ministries to build partnerships between majority and minority culture.

The evening clearly reminded us how rich the body of Christ in our region is, but also the challenges of being better connected with one another and how little we use the resources God has sent to New England via all the diaspora leaders. It is challenging for diaspora leaders to gain access in the Euro-American church context due to social and economic disparities as well as the mere lack of relationships. Therefore, being an advocate, bridge-builder, and agent for reconciliation between majority and minority culture is one of the main missions of Intercultural Ministries of Emmanuel Gospel Center.

We hope that you will join us in this mission!

Christian Engagement with Muslims in the United States

Listen in on a video conversation on Christian engagement with Muslims in the U.S. where panelists talk about positive and objectionable interactions Christians may have with our Muslim neighbors.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 87 — March 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at the Emmanuel Gospel Center, serves as host of a video conversation on the topic of Christian Engagement with Muslims in the U.S., which he hopes “will encourage many to reach out to our Muslim neighbors.” The conversation took place on February 22, 2013, and the panel was comprised of:

Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian–Muslim Relations at EGC;

Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and

Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.

In the first half of the conversation, panelists address “Positive Christian Interactions with Muslims,” which include questions regarding motivation, personal experience, peace-making, and transparency. In the second half, panelists address “Objections and Challenges to Christian Engagement with Muslims,” where they touch on militant Islam, “normative” Islam, “Chrislamism,” interfaith dialogue, and how a local church congregation might respond to a nearby mosque.

We have provided a link and brief description of each of the ten videos, which were produced by Brandt Gillespie of PrayTV and Covenant for New England in a studio located at Congregación León de Judá in Boston. At the end of this issue, we have included a short list of resources suggested by the Intercultural Ministries team of EGC.

Positive Christian Interactions with Muslims

Part One: What is your motivation for working toward positive Christian – Muslim relations?

Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, introduces the subject of Christian-Muslim relations. He introduces his guests: Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian-Muslim Relations at Emmanuel Gospel Center; Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.

Gregg asks his guests what their motivation is for working toward positive Christian-Muslim relations.

Part Two: What are some positive ways you are personally relating to Muslims?

Gregg asks for some positive ways the panelists are personally relating with Muslims and the Muslim community. Nathan describes a “holy texts study” and other initiatives in his role as a minister at Virginia Commonwealth University. Dave talks about his love for Arab culture and his lifestyle of relating to Muslims on a daily basis.

Part Three: What are some other examples of positive Christian engagement with Muslims?

Paul describes ways he is personally relating to Muslims by building friendships, practicing hospitality, and hosting interfaith dialogues. Gregg tells the story of how a Muslim friend named Majdi cared for him when he was sick and challenges Christians to get to know Muslims on a deeper level. Dave shares a dream he has about seeing Christians and Muslims serving together, and Nathan describes some of the recent initiatives of Peace Catalyst International, including “Communities of Reconciliation” and the Evangelicals for Peace Conference held in Washington, D.C. (See http://www.peace-catalyst.net.)

Part Four: Do peacemaking Christians compromise the truth of the Gospel?

In this segment, Gregg presses his guests on the issue of Christian peacemaking by asking if this approach waters down a commitment to the truth of the Gospel. Nathan points out that the Great Commission and the Great Commandment cannot be separated but must go hand-in-hand. Nathan also suggests that not only must we be committed to the message of Jesus but also the “motives and manners” of Jesus. Dave admonishes us to be forthright in sharing the Gospel as part of our authentic Christian witness. Gregg points out the biblical mandate is to live out the doctrine of the incarnation in the way we relate to Muslims before we seek to have a theological conversation about the incarnation.

Part Five: Christian Transparency: What would you say to a Muslim who might be watching this video?

The panelists emphasize the importance of being transparent about our identity as followers of Jesus. Paul speaks of being upfront about who we are (followers of Jesus) and what we want to do (to bear witness to him). Dave speaks about how there are individuals on both sides that may seek to broadly demonize the other side, and we are seeking to counter this. The segment ends by asking each of the panel members to share a word with any Muslim friends who might be watching the video.

Objections & Challenges to Christian Engagement with Muslims

Part One: What about militant Islam?

Gregg frames the subject of challenges to Christian engagement with Muslims in the U.S. by referring to a continuum of response from hostility to naivety. Panel members respond to question: What about militant Islam? Nathan reminds us that militant religiosity is not the sole property of Islam, nor is it as universal among Muslims as some Christians seek to paint it. Dave warns us about the dangers of stereotyping others and the importance of not being paralyzed by fear and hostility. Paul shares his perspective about militant Islam from a South Asian perspective.

Part Two: What is normative Islam?

Gregg asks his guests to respond to the question: What is normative Islam? Dave responds to the question with a question: What is normative Christianity? Paul points out that just as many Christians misunderstand Islam, many Muslims misunderstand Christianity. Nathan reminds us that Muslims themselves should answer the question of normative Islam rather than Christians.

Part Three: Are you in danger of becoming a “Chrislamist”?

Gregg explores with panel members the possibility of compromising Christian truth in the process of promoting interfaith relationships with Muslims. Various subjects are explored, such as “the Common Word” initiative and the threat of being labeled as “Chrislamists.” Gregg concludes by pointing to Jesus as our model when he came “full of grace and truth.”

Part Four: What is the value and limitations of interfaith dialogue?

Gregg explores with panel members the question: What is the value and limitation of interfaith dialogue? Paul underscores how dialogue is the only way to overcome misunderstandings on both sides. Nathan describes how dialogue can be a form of hospitality and lead to authentic friendship. Dave emphasizes the need for discipline and commitment in the dialogue process and that interfaith dialogue (also known as “meetings for better understanding”) can open doors and create space for God to work.

Part Five: What steps could be taken by a church that is in close proximity to a mosque?

Finally, the panel explores the question of how a local church might respond to a mosque that is in close proximity. Dave counsels that a good starting point is for a church to get some good training. Nathan discusses the posture of the church by admonishing with the truism: “One cannot fear what one has chosen to love.” Gregg tells a story of dropping by a local mosque to meet the Imam and some surprising lessons learned in the process. Paul advises that churches should not view a mosque as a threat but as an opportunity for Christian witness.

Resources

The following resources have been suggested by the Intercultural Ministries department of EGC.

Bell, Stephen & Colin Chapman editors. Between Naivety and Hostility: Uncovering the best Christian responses to Islam in Britain. Crownhill, Milton Keyes: Authentic Media, 2011.

Goddard, Hugh. Christians and Muslims: From Double Standards to Mutual Understanding. London: Routledge Curzon, 2003.

McDowell, Bruce A., and Anees Zaka. Muslims and Christians at the Table: Promoting Biblical Understanding among North American Muslims. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Pub., 1999.

Metzger, Paul Louis. Connecting Christ: How to Discuss Jesus in a World of Diverse Paths. Nashville: T. Nelson, 2012.

Nichols, Laurie Fortunak., and Gary R. Corwin. Envisioning Effective Ministry: Evangelism in a Muslim Context. Wheaton, IL.: Evangelism and Missions Information Service, 2010.

Peace Catalyst International www.peace-catalyst.net

Tennent, Timothy C. Christianity at the Religious Roundtable: Evangelicalism in Conversation with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002.

Volf, Miroslav. Allah: A Christian Response. New York: HarperOne, 2011.

Developing Safe Environments for Learning and Transformation

Do you want to see transformation in your organization? You might want to give some thought to the importance of creating a safe environment, where your team can learn together to trust, practice confidentiality, become good listeners, stop judging, and develop a culture of patience, forgiveness, and celebrating the best in one another.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 80 — July 2012

by Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC

I would like to address a question that we have been asked over and over again by Christian leaders and organizations that we have consulted and collaborated with in our work. It goes something like this: How does our organization (or church, denomination, school, etc.) develop a safe environment where our capacity to see personal and corporate transformation in and through our organization (church, denomination, school, etc.) is greatly enhanced? Or to put it another way, how can we experience transformation in our organization so that we have greater capacity to be an agent of transformation in our world?

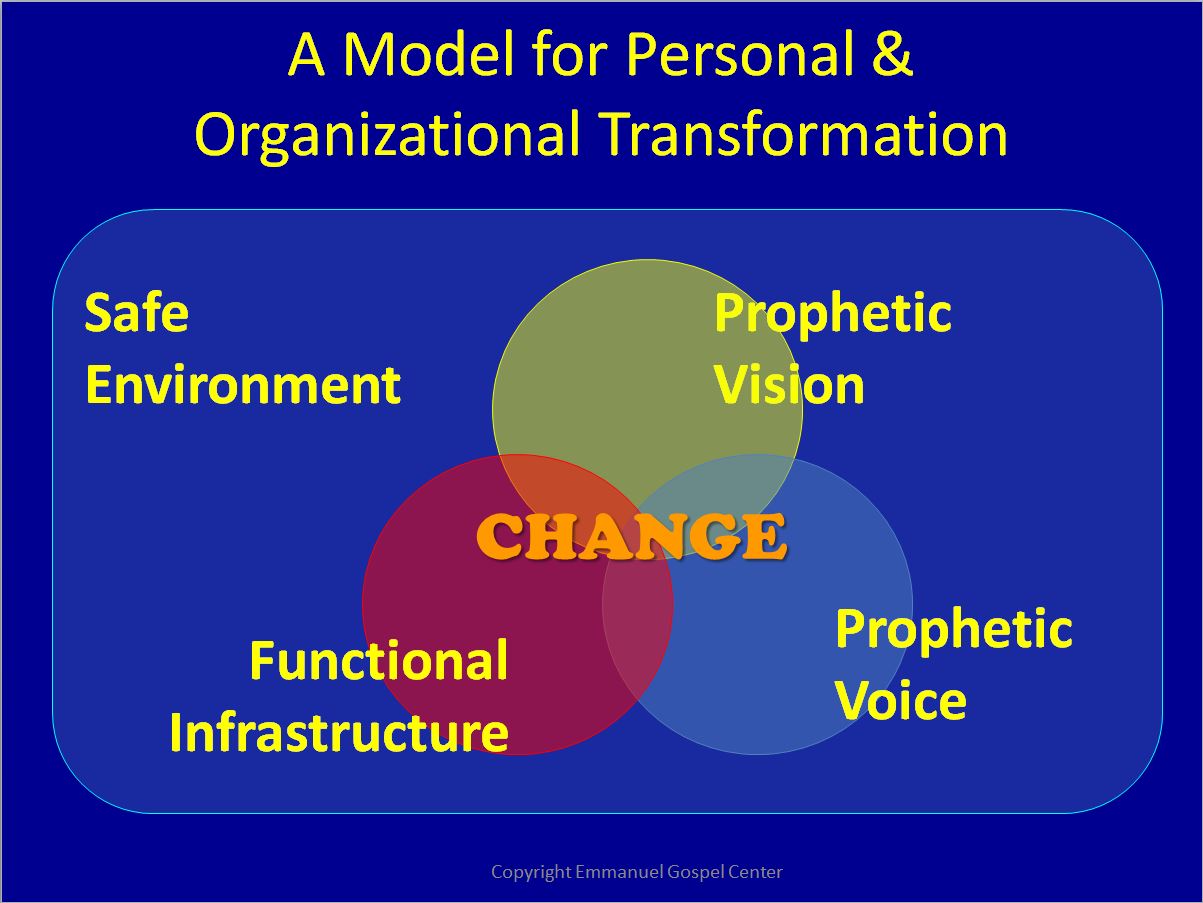

A Model for Personal and Organizational Transformation

Over the past decade, we have with consulted many organizations on the topic of organizational change. In this process, I have often shared a model—or archetype1 — that describes the elements necessary for personal and organizational transformation. I say “personal and organizational” transformation because it is impossible to have one without the other. In our context, we often apply these principles to intercultural work but they are transferable to any desired change.The elements involved can be illustrated in the following Venn diagram:

Figure 1: Model for Transformation

A brief definition of each element follows:

Prophetic Vision is seeing God’s intention for a given situation and seeing the present reality as it really is. Our primary source for prophetic vision is the Word of God, but there are other sources that are also important: the community of faith, the leading and illumination of the Holy Spirit, and social/systems analysis. This prophetic seeing will always reveal a “gap” representing the distance between God’s high calling and where we are in relationship to that high calling. This prophetic seeing must be done with humility, recognizing that as humans we “know in part and prophesy in part.” Hence, prophetic vision is best done in community where others are permitted to share their perspective to help the learning organization fill in the picture as completely as possible and to arrive at “shared vision.”

Prophetic Voice is declaring what we believe God would have us do at this point in time and space. Like prophetic vision, prophetic voice must also be shared and affirmed by a particular Christian community/organization for it to have any traction. While prophetic vision and prophetic voice can arise from anyone within a given Christian community/organization, it must be embraced and endorsed by the “authorizing voice” of that community/organization for it to gain legitimacy and traction.

A Functional Infrastructure must be put in place to carry out the prophetic vision and voice. The core of this infrastructure is an aligned functional team and the necessary support structures to do the work.

A Safe Environment is the necessary context for any and all three of the elements above to work and, hence, is perhaps the most important of the four elements. It is also, in my experience, the element most missing in Christian ministry, and the one that most often derails personal and organizational transformation. A safe environment is necessary for a community/organization to come together to understand prophetic vision, agree on prophetic voice, and build and maintain a functional infrastructure. A safe environment involves establishing, honoring and maintaining honest and loving relationships that have the capacity to sustain and learn from the inevitable conflicts that always arise in the journey of transformation.

Reflections on How To Develop a Safe Environment

The main question of this paper deals with this fourth element: a safe environment. Time and time again in our consulting practice, we hear our clients say something like this: “We clearly see the necessity of creating a safe environment for learning and transformation but we have one question, how exactly do we develop a safe environment?” What follow is a first step in attempting to answer that question.

What a Safe Environment Is and Is Not

Before answering that question, however, let’s first describe what a safe environment is and is not.

When I am consulting with a Christian group, I often get the group to reflect on this question by taking them to what I call “the most unpracticed verse of the Bible”—James 5:16. I read to them the verse from the New International Version: Therefore confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be healed. Or, my preferred rendering of this verse from the Message paraphrase: Make this your common practice: Confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you can live together whole and healed.

I then ask them a series of questions: Do we really “do” this verse in the church? Is it our “common practice”? The answer, “No, not so much.”

Then I follow with, “Why don’t we practice it?” The reply: “Because people don’t feel safe enough to do it.”

I then ask, “What would it take to make it safe enough to actually do it, to make this our common practice? What are the qualities that describe a safe environment?” The lists of qualities are always very similar, things such as:

Trust

Confidentiality

Being a good listener

Not judging others

Patience and longsuffering

Considering the best in one another

Not looking down on those who confess their sins/temptations/weakness

Not “defining” others by "freeze-framing” their identity by the sins/temptations they confess

Avoiding “cross-talk” (being too quick to give unsolicited advice to others)

Focusing on our own “stuff” rather than on others' “stuff”

Gaining trust and asking permission before attempting to speak into someone else’s life

A commitment to one another’s growth

It is also important to explicitly state what a safe environment is NOT. Many people identify the elements above but still misconstrue what a safe environment is because they do not understand the subtler elements of what a safe environment is not.

A safe environment is NOT:

A pain-free environment (growth is often painful)

Only about “me” feeling safe (it is also about helping “others” feel safe)

Uniformity of opinion (a truly safe environment welcomes different perspectives)

A permission slip for being obstinate, unyielding, and unwilling to work for the common good

A “free-for-all” for expressing raw emotions without considering the effect this sharing will have on others

Steps To Developing a Safe Environment

After describing what a safe environment is and is not, the next issue is how to get there. It is one thing to be able to describe a safe environment, it is another thing altogether to be able to create and nurture it. The following diagram describes the process I have observed in creating, nurturing and reproducing safe environments.

Figure 2: The Process of Creating & Reproducing a Safe Environment

Let’s now describe each of the stages of the cycle in more detail.

1. Willingness: A Community/Organization That Desires to Create a Safe Environment

The first step required to enter this journey is “willingness.” As the common quip goes, “A man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still.” Not many high-level organizational leaders will say that they do not want a safe environment within their organizational culture, but many simply have never experienced a safe environment themselves to the degree that they can provide the necessary leadership to cultivate it within their organization.

So the first step, plain and simple, is to find an organization or a community or (more likely) a subset within an organization/community that is willing to pursue a greater intellectual and experiential understanding of what a safe environment really is. In some cases—in a highly dysfunctional organization, for instance—the starting point may necessitate seeking out a safe environment outside of the organization.

2. Skilled Leadership to Guide in Nurturing a Safe Environment

The importance of skilled leadership cannot be overstated. This leadership may come from within the community or from outside it. The real issue here is the quality of leadership. There are certain prerequisites that a leader must have in order to serve as a guide to others in a journey toward a safe environment.

The first and foremost indispensable quality is that the leader must have already experienced the power of a transformational safe environment herself. It is impossible to reproduce and to guide others in what we ourselves have not experienced. The best guides are those who have tasted deeply of the refreshing waters of a safe environment for themselves.

The second quality is that the leader must be whole enough.2 “Whole enough” to have a healthy self-awareness, to appropriately share their journey with others, and to assist others in their journey. The term “whole enough” means that the leader is self-aware of her own brokenness and has already taken significant steps in her own healing journey. Some of the characteristics of a “whole enough” leader are as follows:

The whole enough leader is one who knows and can articulate her own self-identity in all of her complexity—good, bad and ugly. This self-awareness is demonstrated in her ability to see that she is (as we all are) “wonderful, wounded and wicked” and that God has taken this total package and has begun a process of healing and transformation. As such, the whole enough person can freely acknowledge her brokenness while at the same time seeing her goodness as a beloved child of God made in his image.

The whole enough leader is one who has learned how to appropriately share his own healing journey as a gift to others. As the whole enough one is secure in the love of God, he is able to share not only his strengths with others but also his weaknesses. As weaknesses are shared, others are called out of darkness and hiding into a place of safety, light and healing.

The whole enough person has been exposed to a safe environment to a sufficient degree that she understands the structural and spiritual elements necessary for nurturing a safe environment for others. In other words, the whole enough person is familiar enough with the air of a safe environment to recognize what it feels like and is skilled enough to know how to foster such an environment for others.

3. Group Learning About the Qualities of a Safe Environment

It is not enough for a leader to merely embody a safe environment; he must also lead a group of willing souls to consider together what a safe environment is and is not, what it looks like and feels like.

The aforementioned exercise (Group Reflection on James 5:16: confessing our sins to one another) is one of the most effective means I have found for leading a group into a better shared understanding of the qualities that comprise a safe environment.

Another technique is to get members of the group to consider the safest environments they have every encountered in their lives—places where personal and corporate transformation was made possible—and to get them to describe the qualities that were present in those environments.

4. Skilled Leadership that will Model & Maintain a Safe Environment

Once the group has reflected together and has a shared vision of what a safe environment looks like, the leader must lead the way by modeling a willingness to be vulnerable in sharing his own journey. The leader must be willing to share personal testimony that is authentic, transparent and bears witness to the power of transformation within a safe community. Not only must the leader model this, he must remind the group of the qualities of a safe environment and establish some basic ground rules that can help maintain it.3

It is also important to add here that creating and maintaining a safe environment is not like taking a straight-line stroll to the top of a mountain, but is more like a circuitous path of hills and valleys. It is often hard work because it involves fallen creatures that sometimes rub one another the wrong way. In truth, a journey toward a safe environment is not for the fainthearted; it requires ample supplies of humility, long-suffering, repentance, grace, and growth. It is important for participants to understand that this is the nature of the journey and that this reality, in fact, is part of what makes it transformational.

5. Reality Check: A Community/Org that is willing to be Honest About Where They are in the Journey

As a group reflects together on what a safe environment looks and feels like, and as the leader models and seeks to nurture a safe environment, the group will naturally begin to reflect on whether their group and their larger organization/community is a safe place. This sober assessment needs to be encouraged. If a community or organization is unwilling to honestly evaluate where they are in the journey, there will be little hope to see progress within the larger community. In many cases, safe environments must first take hold in smaller subsets of a community/organization before the larger community can be affected to any significant degree.

6. Continued Practice Through “Action-Reflection” Learning

The task of creating and nurturing a safe environment is not a destination but a continuous journey of “action-reflection.” Action-Reflection learning means that there is continuous effort given to putting into practice the qualities of a safe environment and continuous commitment to reflection, learning and evaluation throughout the journey. We learn how to be a safe community by practicing.

7. Reproduction: Members of the Community/Organization Reproduce Safe Environments in their Spheres of Influence

As members of a community/organization taste of the transforming power of a safe learning environment, they will naturally be drawn to bring its influence into their spheres of influence. In fact, I have found that people who have tasted of a safe environment will have a thirst for more and will want to bring it to others within their community/organization and beyond. This point goes back to the Genesis design that God’s creatures “reproduce after their own kind.”4 People who have experienced a safe environment, making personal and corporate transformation possible, will naturally seek out other willing souls and begin the cyclical process described in this paper over again.

Conclusion: Make this your common practice

When the three elements described in the Transformation Model (Figure 1) are practiced within the context of a safe environment, personal and corporate transformation is made possible. Examples of this transformation abound in both the personal and corporate spheres. I have experienced this in my own life, in our own work in Intercultural Ministries, and in our consulting with other organizations. A familiar example—on the personal level—that many people in our society would recognize is Alcoholics Anonymous, but there are many others.5

FOOTNOTES

1 In the discipline of Systems Thinking, a systems archetype is a structure that exhibits a distinct behavior over time and has a very recurring nature across multiple disciplines of science. The foundational text that Systems Thinkers often refer to is The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, by Peter Senge (Currency Doubleday: New York: 1990).

2 I learned the term “whole enough” as a participant in a healing ministry called Living Waters. Living Waters is one of the most effective programs I am aware of in nurturing a safe healing environment, especially for those who have experienced relational and/or sexual brokenness. To learn more about Living Waters, visit http://desertstream.org.

3 These qualities and ground rules were mentioned previously in this article under the subheading “What A Safe Environment Is & Is Not.”

4 Genesis 1:11-12

5 For copies of these case studies please contact the author.

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler is the Director of Intercultural Ministries at Emmanuel Gospel Center. The mission of Intercultural Ministries is “to connect the Body of Christ across cultural lines…for the purpose of expressing and advancing the Kingdom of God… in Boston, New England, and around the world.” Gregg works with a wide cross-section of leaders from over 100 ethno-linguistic groups. His ministry largely involves applied research, training, consulting, networking, and collaboration, especially related to intercultural ministry development.

Prior to joining the staff of EGC in 2001, Gregg served for 13 years as a church planter and pastor of a multicultural church in Boston and was elected as the overseeing Presbyter for the Northeast Massachusetts Section of the Assemblies of God. He served for five years as the Pastor of Missions & Diaspora Ministry at Mount Hope Christian Center in Burlington, Massachusetts. He earned his Doctor of Ministry in Urban Ministry in 2001 from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Ministry in Complex Urban Settings. His thesis, Nurturing Diaspora Ministry and Missions in and through a Euro-American Majority Congregation, has provided much of the direction of his ministry in recent years. Raised in Kansas, Gregg graduated from Evangel University and the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary in Springfield, Missouri. Gregg and his wife, Rita, live in the Boston area and have three children.

Click to Learn more about EGC's Intercultural Ministries.

Ethnic Ministries Summit: Divinity & Dirt

“The Summit was a reality check. And it wasn’t a reality check that the world is becoming more multi-ethnic, but rather that God’s Kingdom is already multi-ethnic, and what am I going to do about it? How am I going to respond?”

“The Summit was a reality check. And it wasn’t a reality check that the world is becoming more multi-ethnic, but rather that God’s Kingdom is already multi-ethnic, and what am I going to do about it? How am I going to respond?”

—Rebekah Kelleher, Student at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston campus, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education

The questions that Rebekah Kelleher voiced following her participation in the Ethnic Ministries Summit are the questions that have been growing at EGC, not only in the past three years as we focused our energies on preparing for the April 2010 Summit, but for over 40 years as dynamic flows of migration have carried nearly one million people from over 100 nations into Greater Boston. Newcomers from Latin America, Asia, and Africa, where Christianity has grown, have helped fuel dynamic Kingdom growth in our region. Other flows bring tremendous opportunity for Christians to relate to some of the world’s most unreached peoples, including Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, and Muslims. We have been asking those questions ever since we became aware of these ethnic streams of spiritual vitality and opportunity. And over the years, EGC has been constantly shaped by our response to these migrations and the way they have profoundly impacted the church, our city, and the region.

Here are some facts which underscore the ethnic diversity of churches in Boston today:

There are more African American churches than any other ethnic church, including White churches.

After African Americans, Whites, and Latinos, the five next most common major ethnic identities of churches are Haitian, other West Indian, multi-ethnic (churches with a broad mix of ethnicities), Asian, and Brazilian.

In the five years between 2001 and 2005, Latinos planted the most new, non-English congregations—approximately one out of every four new congregations.

In 1968, there were no Haitian churches in Boston and Cambridge and only two Haitian Bible studies. Between 2001 and 2005, Haitians planted nine new churches, bringing the total to over 50 churches.

The churches in Boston and Cambridge are becoming internally more diverse and multicultural.

(Facts are from EGC’s research from the Boston Church Directory, 2005.)

THAT THEY MAY BE ONE

In our work since the 1970s to understand and nurture spiritual vitality in the city, we have documented that much of the church’s spiritual vitality has come to New England through the doors of immigration. If this is where God is at work, then this is where his children need to be at work, in this relatively new reality, this new way of defining the church in New England. And it’s not just EGC and our urban ministry partners who need to respond. In growing recognition of the changing demographics in our neighborhoods, towns, and cities—with the world at our doorstep—the 21st century church across North America needs to envision and embrace our new reality as well.

This was the vision behind “A City Without Walls,” the 10th Annual Ethnic Ministries Summit. This vision of a city without walls (from Zech. 2:4-5), a church without division, but united in Christ across cultural and denominational lines, became the uncompromised goal for the Summit. Isn’t this what Jesus was praying for in John 17, when he said of future believers, “so that they may be one as we are one”?

At EGC, we believe that by nurturing authentic connections between the many nations represented in the Body of Christ and the many nations in our own backyard, and by learning from and listening to each other, the resulting love and understanding can tear down walls that hinder unity in the Body of Christ and we will see the Kingdom of God continue to advance in our region. But what does it take to get us to the place where we can be about that work of nurturing?

WEAR KINGDOM LENSES

The place to start is to gain the right perspective of God’s church. Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, director of EGC’s Intercultural Ministries, says that we have to have eyes to see what God is doing in his Kingdom. “And in order to see, we have to make sure we have the capacity to see, to make sure we have the right lenses on.” Wearing “Kingdom lenses,” Gregg explains, means seeing reality as much as possible the way that God sees it and the way the Scripture describes it, rather than through our own limiting mental models (inner assumptions).

To explain what Kingdom lenses are, Gregg first talks about what they are not. He says we don’t want to use our “ethnocentric lenses, when we only see reality through our own ethnic perception or our own ethnic identity.” Neither do we want to use our denominational lenses. “If we only look at what God is doing through our own little narrow denominational lenses, we’re going to miss seeing the complete picture.” Another limiting factor would be what Gregg calls economic reality lenses. “So if we are middle class or upper middle class and we don’t have a connection to a lower economic class, if we are not in touch with that reality, we are going to miss it.” All these lenses are insufficient, he says, and so we have to make sure we have a way of perceiving and communicating with people different from ourselves.

Why is vision important? Gregg says, “God is doing a divine thing, but a lot of us have not been perceptive of the work of the Lord in our midst. And part of his divine working is all these various streams that did not exist three or four decades ago.” As EGC’s research department has worked to identify these streams, we helped to host gatherings of leaders from many cultures to explore and celebrate New England’s ethnic church diversity and vitality. In 2002, we convened a gathering of Boston’s church leaders. Then in 2007, we hosted the Intercultural Leadership Consultation, where 400 diverse leaders gathered to explore the many cultural expressions of the church in the New England region. New England’s Book of Acts is a collection of reports and articles on these New England ethnic streams, produced by EGC for the 2007 Intercultural Leadership Consultation, available online at www.newenglandsbookofacts.org.

DEAL WITH BOULDERS

Part of seeing reality is also to see that all is not well. Diversity, in and of itself, is not the goal. Gregg says, “It isn’t enough just to get diverse people in the same proximity. That in and of itself does nothing. As a matter of fact, it can actually make things degenerate. But if you can work on the element of trust in a diverse community, then that community can have new innovation and new breakthrough and even multicultural teams working at fostering trust and mutuality and respect and listening to one another. Then those communities and those organizations can excel. We have to build that level of trust.”

Trust is hard work. Gregg found this to be true in the journey of the past three years as he met with a dozen leaders from many cultures to plan the Summit. “The journey involved both celebration and repentance, joy and pain, divinity and dirt. Therefore, it required a willingness to navigate in a state of tension between these things as we related to all these different streams in the Body of Christ.” This willingness to operate in the middle of tension became one of the primary takeaways from the Summit journey. “While there is divinity flowing in all these ethnic streams, there are also problems—there’s dirt and boulders and barriers that are impeding the flow as God has intended,” Gregg says. While we celebrate the work of God flowing in these streams, we also want to create an environment where, he says, “we can confess and acknowledge and understand and deal with the dirt and the boulders and the barriers.”

CREATE A SAFE ENVIRONMENT

How does EGC’s Intercultural Ministries deal with the dirt that comes up between and within cultures? “The first thing is that we have to provide good leadership to try to create the necessary environment, a safe environment where we actually are able to model acknowledging the dirt, acknowledging our brokenness, our fallenness, where we are missing the mark of God’s intention.” Gregg says leaders must intentionally model humility and an ability to repent, while we also set up an environment where people feel safer to begin to share some of their brokenness.

Gregg uses the analogy of a family reunion when he is coaching a group to create a safe place to work through differences. While some people love a family reunion and come ready to rejoice and celebrate and enter in, some people really hate family reunions because it shows them all their brokenness. “We are not going to ignore the fact that there is pain and brokenness and fallenness and not everything is perfect in the family, even the family of God on earth, and so we just begin to acknowledge that and model it from the front, and encourage people to share that part of the story.”

FIND GOD'S TRAJECTORY

The best way to deal with the barriers is not in isolation, but in community. Our responsibility is to discern and understand “the trajectory that the Lord is on,” as Gregg says. “In order to understand that, we need to read Scripture, and read it together, as even our understanding of Scripture is culturally bound and formed because of who you are reading Scripture with, and who you are praying with,” he says. “And so my conviction is that if we are reading and praying the Scripture with a diverse community that is coming from different backgrounds and different realities, and we create a listening environment where we are really learning and listening together, we will better perceive what it is that God is headed toward.”