BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Understanding Boston's Quiet Revival

What is the Quiet Revival? Fifty years ago, a church planting movement quietly took root in Boston. Since then, the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled. How did this happen? Is it really a revival? Why is it called "quiet?" EGC's senior writer, Steve Daman, gives us an overview of the Quiet Revival, suggests a definition, and points to areas for further study.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 94 — December 2013 - January 2014

Introduced by Brian Corcoran

Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

Boston’s Quiet Revival started nearly 50 years ago, bringing an unprecedented and sustained period of new church planting across the city. In 1993, when the Applied Research team at the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began to analyze our latest church survey statistics and realized how extensive church planting had been during the previous 25 years, resulting in a 50% net increase in the number of churches, Doug Hall, president, coined the term, “Quiet Revival.” This movement, he later wrote, is “a highly interrelated social/spiritual system” that does not function “in a way that lends itself to a mechanistic form of analysis.” That is why, he theorized, we could not see it for years.* Perhaps because it was so hard to see, it also has been hard to understand all that is meant by the term.

One of the most obvious evidences of the Quiet Revival is that the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled since 1965. Starting with that one piece of evidence, Steve Daman, EGC’s senior writer, has been working on a descriptive definition of the Quiet Revival. It is our hope that launching out from this discussion and the questions Steve raises, more people can grow toward shared understanding and enter into meaningful dialog about this amazing work of God. We also hope that more can participate in fruitful ministries that are better aligned with what God has done and is continuing to do in Boston today. And thirdly, we want to inspire thoughtful scholars who will identify intriguing puzzles which will prompt additional study.

*Hall, Douglas A. and Judy Hall. “Two Secrets of the Quiet Revival.” New England’s Book of Acts. Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007. Accessed 01/24/14.

What is the Quiet Revival?

by Steve Daman, Senior Writer, Emmanuel Gospel Center

What is the Quiet Revival? Here is a working definition:

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

What questions come to mind when you read this description? To start, why did we choose the words: “unprecedented”, “sustained”, “Christian growth”, and “1965”? Can we defend or define these terms? Or what about the terms “revival” and “quiet”? What do we mean? And what might happen to our definition if the revival, if it is a revival, “persists” for more than “five decades”? How will we know if it ends?

These are great questions. But before we try to answer a few of them, let’s add more flesh to the bones by describing some of the outcomes that those who recognize the Quiet Revival attribute to this movement. These outcomes help us to ponder both the scope and nature of the movement:

The number of churches in Boston has nearly doubled since 1965, though the city’s population is about the same now as then.

Today, Boston’s Christian church community is characterized by a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership.

The spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe.

From these we can infer more questions, but the overarching one is this: “How do we know?” Surely we can verify the numbers and defend the first statement regarding the number of churches, but the following assertions are harder to verify. How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? The implication is that these characteristics are valid evidences for a revival and that they have appeared or grown since the start of the Quiet Revival. Further, has “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival… spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”? What evidence is there? If these assertions are true, then indeed we have seen an amazing work of God in Boston, and we would do well to carefully consider how that reality shapes what we think about Boston, what we think about the Church in Boston, and how we go about our work in this particular field.

Numbers tell the story

The chief indicator of the Quiet Revival is the growth in the number of new churches planted in Boston since 1965. The Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began counting churches in 1969 when we identified 300 Christian churches within Boston city limits. The Center conducted additional surveys in 1975, 1989, and 1993.1 When we completed our 1993 survey, our statistics showed that during the 24 years from 1969 to 1993, the total number of churches in the city had increased by 50%, even after it overcame a 23% loss of mainline Protestant churches and some decline among Roman Catholic churches.

That data point got our attention. At a time when people were asking us, “Why is the Church in Boston dying?” the numbers told a very different story.

Just four years before the discovery, when we published the first Boston Church Directory in 1989, we saw the numbers rising. EGC President Doug Hall recalls, “As we completed the 1989 directory and began to compile the figures, we were amazed to discover that something very significant was occurring. But it wasn’t until our next update in 1993 that we knew conclusively that the number of churches had grown—and not by just 30 percent as we had first thought, but by 50 percent! We had been part of a revival and did not know it.”2 It was then Doug Hall coined the term, the Quiet Revival.

Fifty-five new churches had been planted in the four years since the previous survey, bringing the 1993 total to 459. EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote at the time, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.”3

In the 20 years since then, church planting has continued at a robust rate. EGC’s count for 2010 was 575, showing a net gain since the start of the Quiet Revival of 257 new churches. The Applied Research staff at the Center is now in the beginning stages of a new city-wide church survey. Already we have added more than 50 new churches to our list (planted between 2008 and 2014) while at the same time we see that a number of churches have closed, moved, or merged. It seems likely from these early indicators that the number of churches in Boston has continued to increase, and the total for 2014 will be larger than the 575 we counted in 2010, getting us even closer to that seductive “doubling” of the number since 1965, when there were 318 churches.4

Regardless of where we go with our definition, what terms we use, and what else we may discover about the churches in Boston, this one fact is enough to tell us that God has done something significant in this city. We have seen a church-planting movement that has crossed culture, language, race, neighborhood, denomination, economic levels, and educational qualifications, something that no organization, program, or human institution could ever accomplish in its own strength.

Defining terms

Let’s return to our working definition and consider its parts.

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

“Quiet”

The term “quiet” works well here because of its obvious opposite. We can envision “noisy” revivals, very emotional and exciting local events where participants may experience the presence of the Holy Spirit in powerful ways. If something like that is our mental model of revival, then to classify any revival as “quiet” immediately gets our attention and tempts us to think that maybe something different is going on here. How or why could a revival be quiet?

In this case, the term “quiet” points to the initially invisible nature of this revival. Doug Hall used the term “invisible Church” in 1993, writing that researchers tend “to document the highly visible information that is pertinent to Boston. We also want to go beyond the obvious developments to discover a Christianity that is hidden, and that is characteristically urban. By looking past the obvious, we have discovered the ‘invisible Church.’”5

An uncomfortable but important question to ask is, “From whom was it hidden?” If we are talking about a church movement starting in 1965, we can assume that the majority of people who may have had an interest in counting all the churches in the city—people like missiological researchers, denominational leaders, or seminary professors—were probably predominantly mainline or evangelical white people. This church-planting movement was hidden, EGC’s Executive Director Jeff Bass says, because “the growth was happening in non-mainline systems, non-English speaking systems, denominations you have never heard of, churches that meet in storefronts, churches that meet on Sunday afternoons.”6

Jeff points out that EGC had been working among immigrant churches since the 1960s, recognizing that God was at work in those communities. “We felt the vitality of the Church in the non-English speaking immigrant communities,” he says. Through close relationships with leaders from different communities, beginning in the 1980s, EGC was asked to help provide a platform for ministers-at-large who would serve broadly among the Brazilian, the Haitian, and the Latino churches. “These were growing communities, but even then,” Jeff says, “these communities weren’t seen by the whole Church as significant, so there was still this old way of looking at things.”7 Even though EGC became totally immersed in these diverse living systems, we were also blind to the full scale of what God was doing at the time.

Gregg Detwiler, director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, calls this blindness “a learning disability,” and says that many Christian leaders missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston through sociological oversight. “By sociological oversight, I am pointing to the human tendency toward ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is a learning disability of evaluating reality from our own overly dominant ethnic or cultural perspective. We are all susceptible to this malady, which clouds our ability to see clearly. The reason many missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston was because they were not in relationship with where Kingdom growth was occurring in the city—namely, among the many and varied ethnic groups.”8

The pervasive mental model of what the Church in Boston looks like, at least from the perspective of white evangelicals, needs major revision. To open our arms wide to the people of God, to embrace the whole Body of Christ, whether we are white or people of color, we all must humble ourselves, continually repenting of our tendency toward prejudice, and we must learn to look for the places where God, through his Holy Spirit, is at work in our city today.

We not only suffer from sociological oversight, Gregg says, but we also suffer from theological oversight. “By theological oversight I mean not seeing the city and the city church in a positive biblical light,” he writes. “All too often the city is viewed only as a place of darkness and sin, rather than a strategic place where God does His redeeming work and exports it to the nations.” The majority culture, especially the suburban culture, found it hard to imagine God’s work was bursting at the seams in the inner city. Theological oversight may also suggest having a view of the Church that does not embrace the full counsel of God. If some Christians do not look like folks in my church, or they don’t worship in the same way, or they emphasize different portions of Scripture, are they still part of the Body of Christ? To effectively serve the Church in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center purposes to be careful about the ways we subconsciously set boundaries around the idea of church. We are learning to define “church” to include all those who love the Lord Jesus Christ, who have a high view of Scripture, and who wholeheartedly agree to the historic creeds.

If we can learn to see the whole Church with open eyes, maybe we can also learn to hear the Quiet Revival with open ears, though many living things are “quiet.” A flower garden makes little noise. You cannot hear a pumpkin grow. So, too, the Church in Boston has grown mightily and quietly at the same time. “Whoever has ears to hear,” our Lord said, “let them hear” (Mark. 4:9 NIV).

“Revival”

What is revival? A definition would certainly be helpful, but one is difficult to come by. There are perhaps as many definitions as there are denominations. All of them carry some emotional charge or some room for interpretation. Yet the word “revival” does not appear in the Bible. As we ask the question: “Is the Quiet Revival really a revival?” we need to find a way to reach agreement. What are we looking for? What are the characteristics of a true revival?

Tim Keller, founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, has written on the subject of revival and offers this simple definition: “Revival is an intensification of the ordinary operations of the work of the Holy Spirit.” Keller goes on to say it is “a time when the ordinary operations of the Holy Spirit—not signs and wonders, but the conviction of sin, conversion, assurance of salvation and a sense of the reality of Jesus Christ on the heart—are intensified, so that you see growth in the quality of the faith in the people in your church, and a great growth in numbers and conversions as well.”9 This idea of intensification of the ordinary is helpful. If church planting is ordinary, from an ecclesiological frame of reference, then robust church planting would be an intensification of the ordinary, and thus a work of God.

David Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland, states in Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts, that there are several types or “patterns” of revival. First, revival commonly means “an apparently spontaneous event in a congregation,” usually marked by repentance and conversions. Secondly, it means “a planned mission in a congregation or town.” This practice is called revivalism, he notes, “to distinguish it from the traditional style of unprompted awakenings.” Bebbington’s third pattern is “an episode, mainly spontaneous, affecting a larger area than a single congregation.” His fourth category he calls an awakening, which is “a development in a culture at large, usually being both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” In summary, “revivals have taken a variety of forms, spontaneous or planned, small-scale or vast.”10

These are helpful categories. Using Bebbington’s analysis, we would say the Quiet Revival definitely does not fit his first and second patterns, but rather fits into his third and fourth patterns. The Quiet Revival was mainly spontaneous. While we can assume there was planning involved in every individual church plant, the movement itself was too broad and diverse to be the result of any one person’s or one organization’s plan. The Quiet Revival seems to have emerged from the various immigrant communities across the city simultaneously, and has been, as Bebbington says, “both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” The Quiet Revival was and is vast, city-wide, regional, and not small-scale.

Since at least the 1970s, and maybe before that, many people have proclaimed that New England or Boston would be a center or catalyst for a world-wide revival, or possibly one final revival before Christ’s return. But even that prophecy, impossible to substantiate, is hard to define. What would that global revival actually look like? Scripture seems to affirm that the Church grows best under persecution. That is certainly true today. Missionary author and professor Nik Ripken11 has chronicled the stories of Christians living in countries where Christianity is outlawed and gives remarkable testimony to the ways the Church thrives under persecution. Yet it would seem that what people describe or hope for when they talk about revival in Boston has nothing to do with persecution or hardship.

Dr. Roberto Miranda, senior pastor of Congregación León de Judá in Boston, has revival on his mind. In addition to a recent blog on his church’s website reviewing a book about the Scottish and Welsh revivals, he spoke in 2007 on his vision for revival in New England.12 Despite the fact that few agree on what revival looks like and what we should expect, should God send even more revival to Boston, the subject is always close at hand.

Again, it is interesting that so many Christians would miss seeing the Quiet Revival when there were so many voices in the Church predicting a Boston revival during the same time frame. Many of them, no doubt, are still looking.

“unprecedented”

As mentioned earlier, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote in 1993, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.” What Rudy wrote in 1993 continues to be true today, as it appears the rate of church planting has not fallen off since then. Never before has Boston seen such a wave of new church development. God, indeed, has been good to Boston.

“sustained”

The EGC Applied Research team will be able to assess whether or not the Quiet Revival church planting movement is continuing once we complete our 2014 survey. It is remarkable that the Quiet Revival has continued for as long as it has. The next question to consider is “why?” What are the factors that have allowed this movement to continue for so long unabated? What gives it fuel? We may also want to know who are the church planters today, and are they in some way being energized by what has gone on during the previous five decades?

Rev. Ralph Kee, a veteran Boston church planter, and animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, wants to see new churches be “churches that plant churches that plant churches.” He says we need to put into the DNA of a new church this idea that multiplication is normal and expected. He has documented the genealogical tree of one Boston church planted in 1971 that has since given birth to hundreds of known daughter and granddaughter and great-granddaughter churches. Is the Quiet Revival sustained because Boston’s newest churches naturally multiply?

Another reason the Quiet Revival has continued for decades may be the introduction of a contextualized urban seminary into the city as the Quiet Revival was gaining momentum. EGC recently published an interview with Rev. Eldin Villafañe, Ph.D., the founding director of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), the Boston campus of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and a professor of Christian social ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Dr. Villafañe confirmed CUME was shaped by the Quiet Revival. But as both are interconnected living systems, CUME also shaped the revival, giving it depth and breadth.

“One of the problems with revivals anywhere,” Dr. Villafañe points out, “is oftentimes you have good strong evangelism that begins to grows a church, but the growth does not come with trained leadership, educated biblically and theologically. You can have all kinds of problems. Besides heresy, you can have recidivism, people going back to their old ways. The beautiful thing about the Quiet Revival is that just as it begins to flourish, CUME is coming aboard.”13

CUME was in place as a contextualized urban seminary to “backfill theology into the revival,” as Jeff Bass describes it, training thousands of local, urban leaders since 1976, with 300 students now attending each year.

“Christian growth”

We use the words “Christian growth” rather than “church growth” for a reason. We want to move our attention beyond the numbers of churches to begin to comprehend how these new churches may have influenced the city. Surely it is not only the number of churches that has grown. The number of people attending churches has also grown. One of the goals of the EGC Applied Research team is to document the number of people attending Boston’s churches today.14

But as we look beyond the number of churches and the number of people in those churches, we also want to see how these people have impacted the city. “Christians collectively make a difference in society,”15 says Dana Robert, director of the Center for Global Christianity and Mission at Boston University. Exploring and documenting the ways that Christians in Boston have made an impact on the city, showing ways the city has changed during the Quiet Revival, would be an important and valuable contribution to the ongoing study of Christianity in Boston.

“city of Boston”

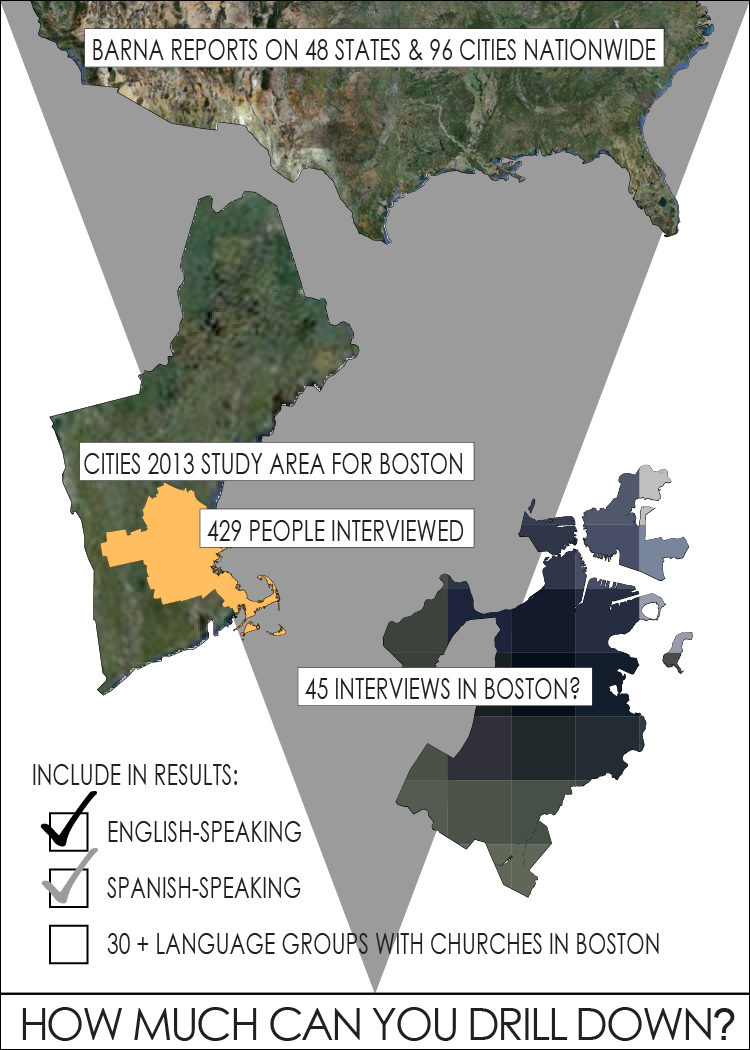

We mean something very specific when we say “the city of Boston.” As Rudy Mitchell pointed out in the April 2013 Issue of the Review, one needs to understand exactly what geographical boundaries a particular study has in mind. “Boston” may mean different things. “This could range from the named city’s official city limits, to its county, metropolitan statistical area, or even to a media area covering several surrounding states.” Regarding the Quiet Revival, we mean Boston’s official city limits which today include distinct neighborhoods such as Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, East Boston, etc., all part of the city itself.

Boston’s boundaries have not changed during the Quiet Revival, but when we have occasion to look further back into history and consider the churches active in Boston in previous generations, we need to adjust the figures according the where the city’s boundary lines fell at different points in history as communities were absorbed into Boston or as new land was claimed from the sea.

EGC’s data gathering and analysis is, for the most part, restricted to the city of Boston, as we have described it. However, the Center’s work through our various programs often extends beyond these boundaries through relational networks, and we see the same dynamics at work in other urban areas in Greater Boston and beyond. It would be interesting to compare the patterns of new church development among immigrant populations in these other cities with what we are learning in Boston. There is, for example, some very interesting work being done on New York City’s churches on a Web site called “A Journey Through NYC Religions” (http://www.nycreligion.info/).

“1965”

We chose 1965 as a start date for the Quiet Revival for two reasons. First, there seems to be a change in the rate of new church plants in Boston starting in 1965. Of the 575 churches active in Boston in 2010, 17 were founded throughout the 1950s, showing a rate of less than 2 per year. Seven more started between 1960 and 1963 while none were founded in 1964, still progressing at a rate of less than 2 per year. Then, over the next five years, from 1965 to 1969, 20 of today’s churches were planted (averaging 4 per year); about 40 more were launched in the 1970s (still 4 per year), 60 in the 1980s (averaging 6 per year), 70 in the 1990s (averaging 7 per year), and 60 in the 2000s (6 per year). Again, we are counting only the churches that remain until today. A large number of others were started and either closed or merged with other churches, so the actual number of new churches planted each year was higher.

Another reason for choosing 1965 as the start date was that the Immigration Act of 1965 opened the door to thousands of new immigrants moving into Boston. Our research shows that the majority of Boston’s new churches were started by Boston’s newest residents, and that that trend continued for years. For example, of the 100 churches planted between 2000 and 2005, about 15% were Hispanic, 10% were Haitian, and 6% were Brazilian. At least 5% were Asian and another 7% were African. Not more than 14 of the 100 churches planted during those years were primarily Anglo or Anglo/multiethnic. The remaining 40 to 45% of new churches were African American, Caribbean or of some other ethnic identity.

Throughout the first few decades of the Quiet Revival, most, but not all new church development occurred within the new immigrant communities. At the same time many immigrant communities experienced significant growth in Boston, the African American population was also growing, showing an increase of 40% between 1970 and 1990. Between 1965 and 1993, although 39 African American churches closed their doors, well over 100 new ones started, for a net increase of about 75 churches. Among today’s total of 140 congregations with an African American identity, 57 were planted during those early years of the Quiet Revival between 1965 and 1993. Many of these churches have grown under skilled leadership to be counted among the most influential congregations in Boston, and new Black churches continue to emerge.

The year 1965 was a year of much change. While we point to these two specific reasons for picking this start date for the Quiet Revival (the change in the rate of church planting in Boston and the Immigration Act of 1965), there were other movements at play. A charismatic renewal began to sweep across the country at that time starting in the Catholic and Episcopal communities on the West Coast. Close on its heels was the Jesus Movement. Vatican II, which was a multi-year conference, coincidentally closed in 1965, bringing sweeping changes to the Roman Catholic community. Socially, the civil rights movement was front and center during those years.

It seems obvious from the evidence of who was planting churches that one of the main influencing factors was the Pentecostal movement among the immigrant communities. It may also be helpful to explore some of the other cultural movements occurring simultaneously to see if other influences helped to fan the flames. We may discover that in addition to immigration factors, various other streams—whether cultural, Diaspora, theological, or social—were used by God to facilitate the growth of this movement.

Boston’s population

Some may wrongly assume that the growing number of new churches in Boston must relate to a growing population. This is certainly not true of Boston. The population of the city of Boston was 616,326 in 1965 and forty-five years later, in 2010, was very nearly the same at 617,594. During those years, however, the population actually declined by more than 50,000 to 562,994 in 1980. This shows that this remarkable increase in the number of churches is not the result of a much larger population.

While the population total was about the same in 2010 as it was in 1965, the makeup of that population has changed dramatically through immigration and migration, and this is a very significant factor in understanding the Quiet Revival.

One issue that still needs to be addressed is Boston’s church attendance in proportion to the population. Based on our current research and over 40 years’ experience studying Boston’s church systems, we estimate that this number has increased from about 3% to as much as perhaps 15% during this period. EGC is preparing to conduct additional comprehensive research to accurately assess the percentage of Bostonians who attend churches.

The other indicators

How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? What evidence is there that “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”?

The work required to clearly document and defend these statements is daunting. These issues are important to the Applied Research staff, and we welcome assistance from interested scholars and researchers to help us further develop these analyses. In a future edition of this journal, we may be able to start to bring together some evidences to support these assertions, but we do not have the time or space to do more than to give a few examples here.

We have compiled information relevant to each of these specific areas. For example, we have evidence of more expressions of unity among churches and church leaders, such as the Fellowship of Haitian Evangelical Pastors of New England. We continue to discover more collaborative networks, and more prayer movements, such as the annual Greater Boston Prayer Summit for pastors, which began in 2000. We can point to churches and church systems that have grown to maturity and are bearing much fruit in both the proclamation of the Gospel and in social ministries, such as the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. We are aware of several excellent organizations and schools where leaders may be trained and grow in their skills, in knowledge, and in collaborative ministry.16

For the staff of EGC, this is all far more than an academic exercise. We work in this city and many of us make it our home as well. It is a vibrant and exciting place to be, precisely because the Quiet Revival has changed this city on so many levels. Doug and Judy Hall, EGC’s president and assistant to the president, have been serving in Boston at EGC since 1964, and they have observed these changes. A number of others on our staff have also been working among these churches for decades, including Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell, who started studying churches and neighborhoods in 1976. Doug Hall says that in the 1960s, it was hard to recommend many good churches, ones for which you would have some confidence to suggest to a new believer or new arrival. Not so today. Today in Boston there are many, many healthy and vibrant churches to choose from all across the city. Our understanding of the Quiet Revival is not only a matter of statistics, it is our actual experience as our work puts us in a position to constantly interact with church leaders representing many different communities in the city.

It appears from this vantage point that the rate of church planting in Boston continues to be robust as we approach the 50-year mark for the Quiet Revival. We are looking forward with excitement to see what the new numbers are when the 2014 church survey is complete. It also appears from the many evidences gained through our relational networks across Boston that these additional indicators of the Quiet Revival also continue to grow stronger.

Notes

(If the resources below are not linked, it is because in 2016 we migrated from EGC’s old website to a new site, and not all documents and pages have been posted. As we are able, we will repost articles from the Emmanuel Research Review and link those that are mentioned below. If you have questions, please click the Take Action button below and Contact Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher.)

1We have written in previous issues about these surveys. See the following editions of the Emmanuel Research Review: No. 18, June 2006, Surveying Churches; No. 19, July/August 2006, Surveying Churches II: The Changing Church System in Boston; No. 21, October 2006, Surveying Churches III: Facts that Tell a Story.

2Daman, Steve. “1969-2005: Four Decades of Church Surveys.” Inside EGC 12, no. 5 (September-October, 2005): p. 4.

3Mitchell, Rudy. “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches.” in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-14.

4We estimate the number of churches in 1965 was 318, based on information derived from Polk’s Boston City Directory (https://archive.org/details/bostondirectoryi11965bost) for that year and adjusted to include only Christian churches. In 1965, many small, newer African American churches were thriving in low-cost storefronts and many of the smaller neighborhood mainline churches had not yet closed or moved out of the city (but many soon would). While there were not yet many new immigrant churches, the city's African American population was growing very significantly and also expanding into new neighborhoods where new congregations were needed.

5Hall, Douglas A., from the Foreword to the section entitled “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches” by Rudy Mitchell, in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-1.

6Daman, Steve. “EGC’s Research Uncovers the Quiet Revival.” Inside EGC 20, no. 4 (November-December 2013): p. 2.

7Ibid.

8Emmanuel Research Review, No. 60, November 2010, There’s Gold in the City.

9Keller, Tim. “Questions for Sleepy and Nominal Christians.” Worldview Church Digest, March 13, 2013. Web. Accessed January 27, 2014.

10Bebbington, D W. Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. p.3.

11Ripken, Nik. personal website. n.d. http://www.nikripken.com/

12Miranda, Roberto. “A vision for revival in New England.” April 7, 2006. Web.

13Daman, Steve. “The City Gives Birth to a Seminary.” Africanus Journal Vol. 8, No. 1, April 2016, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Center for Urban Ministerial Education. p. 33.

14We wrote about the difficulties national organizations have in coming up with that figure in a previous edition of the Review: No. 88, April 2013, “Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Greater Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical?”

15Dilley, Andrea Palpant. “The World the Missionaries Made.” Christianity Today 58, no. 1 (January/February 2014): p. 34. Web. Accessed: January 30, 2014. Dilley quotes Robert at the end of her article on the impact some 19th century missionaries had shaping culture in positive ways.

16A number of educational opportunities for church leaders are listed in the Review, No. 70, Sept 2011, “Urban Ministry Training Programs & Centers.”

TAKE ACTION

We have mentioned throughout this article that we would welcome scholars, researchers, and interns who could help contribute to our understanding of this movement in Boston.

Note: Some document links might connect to resources that are no longer active.

Serving Cambodian Pastors

On Friday, March 4, 2005, Pastor Reth Nhar said goodbye to his wife, climbed into a car with four Cambodian friends, and headed out into the evening rush hour for the 60-mile drive north out of Providence, through the heart of Boston, to Lynn, Massachusetts. There the five made their way up to the second floor of an office building at 140 Union Street, grabbed some tea, and at 6:45 p.m., they crammed into a meeting room at the new Cambodian Ministries Resource Center.

Serving Cambodian Pastors: Every Tribe & Tongue & People & Nation

Reaching out to the mission field in our neighborhoods

On Friday, March 4, 2005, Pastor Reth Nhar said goodbye to his wife, climbed into a car with four Cambodian friends, and headed out into the evening rush hour for the 60-mile drive north out of Providence, through the heart of Boston, to Lynn, Massachusetts. There the five made their way up to the second floor of an office building at 140 Union Street, grabbed some tea, and at 6:45 p.m., they crammed into a meeting room at the new Cambodian Ministries Resource Center.

Convening on the first weekends of February, March and April this year, the class, “Evangelism in the Local Church,” is part of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s urban extension program, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME). On Friday evenings, the 17 students from seven churches and their two instructors meet from 6:45 to 9:45. Then they are back on Saturdays from 9:00 to 4:00. The schedule is designed for busy bi-vocational pastors, like Reth, and church lay leaders who want to pursue a seminary education but need to fit it into their already busy lives.

This is the first class at CUME taught in Khmer.* Rev. PoSan Ung, a missionary with EGC, teaches in Khmer. Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Multicultural Ministries Coordinator with EGC, co-teaches in English. Asked in a survey if they would prefer to take the course in English or Khmer, some students said they were more comfortable in one language and some in the other. This, according to Gregg, “reflects the reality of a community in transition.” When a guest speaker presents in English, PoSan will translate key concepts into Khmer.

Rev. PoSan Ung established the Cambodian Ministries Resource Center last year to help support the growing ministry of Cambodian Christians in New England. There he offers Christian literature in Khmer, as well as meeting and office space. PoSan is also planting a church in Lynn, reaching out to young, second-generation Cambodians. Having lived through the Cambodian Holocaust and grown up as a refugee, PoSan is intimately in touch with the Cambodian experience. For the past ten years, he has served in various churches in New England as a youth pastor, as the English-ministry pastor for a Cambodian church, and as a church planter. Since 2000, PoSan has worked to develop a ministry that extends to church leaders in the Cambodian Christian community across New England and reaches all the way to Cambodia.

According to PoSan, “The Greater Boston area has the second largest Cambodian population outside Cambodia. However, there are merely a handful of Christians. Thus the Cambodian community is a mission field, in desperate need of enabled, equipped and supported workers.”

In 2000, this need among Cambodians was not in focus at EGC. But that was the year we teamed with Grace Chapel in Lexington to research unreached people groups within the I495 belt of Eastern Massachusetts, and to identify indigenous Christian work being carried on among them. As a result of that research, a joint Grace Chapel and EGC team began to help pastors and leaders gather together to form the Christian Cambodian American Fellowship (CCAF). The aim of the CCAF is to find avenues for training and equipping Cambodian leaders and for planning collaborative outreaches and activities that strengthen and encourage Kingdom growth among Cambodians.

Multicultural Ministries

That work also informed the development of EGC’s Multicultural Ministries program. While we have worked with ethnic churches since the ’60s, a vision was growing to do more to encourage ministry among the region’s immigrant populations who were settling not only in Boston, but in urban communities around Boston. To put flesh on this vision, Gregg Detwiler joined the EGC team.

Rev. Gregg Detwiler served as a church planting pastor in Boston for twelve years. He then served as the Missions-Diaspora Pastor at Mount Hope Christian Center in Burlington, where a ministry emerged to serve people from many nations. In 2001, he earned a Doctor of Ministry degree from Gordon-Conwell through CUME and started his multicultural training and consulting work with a dual missions appointment from EGC and the Southern New England District of the Assemblies of God.

In time, as Gregg pursued open doors of opportunity to serve ethnic communities in Greater Boston and to consult in multicultural ministry collaboration, four streams of service developed, the first being to support the CCAF.

1. Supporting CCAF

“My role in the fellowship is that of a supportive missionary who seeks to encourage and promote the indigenous development of the faith,” Gregg explains. The CUME class came out of listening to the Cambodians in the CCAF, and was a concrete response to the needs they expressed. “In the past year, we have seen participation in the CCAF broaden and deepen. By this I mean that we have come to a place where we are now dealing with some of the deeper issues hindering the Cambodian churches from expanding.” The CUME class is another major leap forward toward this broadening and deepening.

2. Multicultural Ministry Training and Consulting

Gregg lumps much of his daily work under this broad category. He provides training and consulting for churches and organizations that wish to learn how to better respond to and embrace cross-cultural and multicultural ministry. For example, in February, Gregg conducted a workshop at Vision New England’s Congress 2005 on “Multicultural Issues and Opportunities Facing the Church,” co-led by Rev. Torli Krua, a Liberian church leader and pastor. At times, Gregg is called upon to serve as a minister-at-large, responding in practical ways to needs and crises within ethnic Christian movements. He serves as a catalyst for collaborative strategic outreaches such as sponsoring an evangelistic drama outreach to the Indian community of Greater Boston. Gregg has worked to form racial and ethnic diversity teams at churches and for his denomination. He is also available for preaching, teaching, workshops, and organizational training for churches wanting to be more multicultural or more responsive to their multicultural neighbors.

3. Multicultural Leaders Council Development

On November 9, 2002, nearly 200 leaders from 16 people groups gathered at the Boston Missionary Baptist Church for an event called the Multicultural Leadership Consultation. Gregg, Doug and Judy Hall, and a diverse team worked for over nine months to plan the gathering. The event served to build relationships, heighten awareness, and launch the Multicultural Leaders Council (MLC).

The MLC is comprised of key ethnic leaders from a variety of ethnic groups, currently 15. The aim of the MLC is to find ways to strengthen Kingdom growth in each of the respective people groups, while at the same time seeking to identify with, learn from, and relate to the wider Body of Christ. Gregg explains, “In this unique context, Cambodian leaders can learn from Chinese leaders, Chinese leaders can learn from Haitian leaders, and Caucasian leaders can learn from them all—and vice versa! Also, resources can be shared that can benefit all of the ethnic movements.

“We meet once a quarter, averaging around 20 to 30 leaders. This year we are focusing most of our energies on two areas: corporate prayer and youth ministry development. In both of these, we are working with the infrastructure already in place in the city that wants to see that happen. The Boston Prayer Initiative is fostering corporate prayer. We believe that multicultural collaboration will not happen outside a climate of prayer. In the area of youth ministry development, we are working with Rev. Larry Brown and EGC’s Youth Ministry Development Project. Larry has come to meet with the MLC to let the people of the MLC influence what he is doing, while he influences the work going on among the youth in various ethnic communities by providing consulting, networking and leadership training for youth workers.”

4. Urban/Diaspora Leadership Training

In addition to his work with the Cambodian class, Gregg works closely with Doug and Judy Hall in teaching CUME core courses in inner-city ministry. “I am now considered a ‘teaching fellow.’ That is not quite a full-grown professor! I teach and grade half of the papers, I am responsible for half of the 46 students currently enrolled in Inner-City Ministry. This is a natural fit for me, as those students are African, Asian, Latin American, Jewish, Caucasian, African American—it’s a natural environment for a cross-cultural learning environment.”

A New Cultural Landscape

A flow of new immigrants into Boston and cities and towns of all sizes is altering social and spiritual realities, providing both blessings and challenges to the American church. One of these blessings is the importing of vital multicultural Christianity from around the world. This vitality has produced thousands of vibrant ethnic churches, and is increasingly touching the established American church.

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler embraces the new realities of our multicultural world and is working to find new ways to allow that diversity and cultural mix to influence our response to the Great Commission of Christ. Gregg says, “I am convinced that if churches in America effectively reach and partner with the nations at our doorstep, God will increase our effectiveness in reaching the nations of the world.” To Gregg, this hope is not merely a theoretical idea or a worthy goal, it is a reality he enjoys every working day.

[published in Inside EGC, March-April, 2005]

The Story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston

About 30% of all Brazilians living in the U.S., approximately 68,197, reside in New England and Portuguese is the third most spoken language after English and Spanish in the region. What are the strengths and opportunities of the predominant Brazilian-speaking churches in New England today? Kaye Cook and Sharon Ketcham offer a quick update on the status of New England’s Brazilian churches, their history, strengths and challenges.

The Story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston

by Kaye V. Cook, Ph.D. and Sharon Ketcham, Ph.D.

an updated analysis based on work done previously by Pr. Cairo Marques and Pr. Josimar Salum in New England’s Book of Acts, Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007

Brazilians in New England

About 30% of all Brazilians living in the U.S. reside in New England (approximately 68,197 Brazilians according to the Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2012), and Portuguese is the third most spoken language after English and Spanish in New England (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Brazilian churches in the Boston area are strikingly dynamic, and there is significant turnover in pastors as well as attendees, often because individuals go back and forth to Brazil.

What are the strengths and opportunities of the predominant Brazilian-speaking churches in Greater Boston today? Before we answer that question, we need to consider the roots of Boston’s Brazilian church community.

History and Contemporary Context

The history of Brazilian churches in Boston is very much shaped by the context of Brazil. Historically, the dominant religion in Brazil is Catholicism, which was the religion of the Portuguese settlers (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). However, fewer people in Brazil today report being Catholic than in previous generations. Whereas more than 90% of Brazilians reported being Catholic as recently as 1970, 65% reported being Catholic in the 2010 census (PEW, 2013).*

The largest Pentecostal church group in Brazil is the Assemblies of God (Assembleias de Deus) with more than 23 million members (Johnson & Zurlo, 2016). Spiritualist religions, which emphasize reincarnation and communication with the spirits of the dead, are also common. More recently, Protestantism―especially Pentecostalism―has had a major impact with 22% reporting being Protestant as of 2010 (Pew, 2013). The earlier Protestant influence was a result of missionary work and church planting, but most of the major Protestant denominations now have an indigenous presence in the country (Freston, 1999) and today’s Brazilian Protestant church is strikingly indigenous.

Pentecostals in Brazil resist typology because of their rapid growth and diversity. The historical Pentecostals (primarily those growing out of missionary endeavors such as those by the Foursquare Church) emphasize the Holy Spirit, the Spirit’s manifestations in gifts, separation from the world, and a high behavioral code. NeoPentecostals such as participants in the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, a denomination which was established in 1977, continue to emphasize the Holy Spirit, especially healing and exorcism, and make connections between Christianity, success, and happiness. NeoPentecostals may also move away from a separatist worldview and strict behavioral standards and toward increased cultural integration, and some emphasize prosperity rather than a central focus on Christ and the Bible (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). The movement toward greater cultural integration has opened doors for political activity (Freston, 1999). There is debate however about whether NeoPentecostalism can be reliably distinguished from Pentecostalism (Gedeon Alencar, personal communication, 3 October 2015). Some also suggest that PostPentecostalism is the preferred term for those who operate in a way that is similar to a business, emphasize cultural integration, and bypass the traditional elements of Pentecostalism such as the “central focus on Christ and the Bible,” focusing instead on a prosperity gospel (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012, p. 159).

Pentecostals (including NeoPentecostals) comprise 85% of the Protestants in Brazil (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). Five years following the 1906-1909 Azusa Street revivals, the rapid expansion of Pentecostalism reached Brazil through Swedish Baptist missionaries (Chesnut, 1997). Due to urbanization and the growth of the mass media (Freston, 1999), there was simultaneous growth among Pentecostals in the North (Belem) and Southeast (São Paulo) regions. Much of the recent growth in Brazil is accounted for by six denominations, three of which are of Brazilian origin: Brazil for Christ, God Is Love, and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (Freston, 1999).** The most rapid recent growth in Brazil among Pentecostals is due to growth in the Foursquare (or Quadrangular) Church, Brazil for Christ, and God Is Love (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012).

According to the IBGE Census, in 2010 there were almost 4 million Baptists in Brazil represented by the Brazilian Baptist Convention (affiliated with the U.S. Southern Baptist Convention) and the National Baptist Convention (Renewalist Baptists). In addition, Reformed churches were common such as the Presbyterian Church of Brazil, the Independent Presbyterian Church, and the Renewed Presbyterian Church. Adventists, Lutherans, and Wesleyans were also represented.

Baptists

According to Marques and Salum (2007), Pastor Joel Ferreira was the first Brazilian Minister to start a Portuguese-speaking church in New England. No interviewee knew of an earlier presence. Pastor Ferreira was a member of the National Baptist Church in Brazil and planted a Renewed Baptist Church in Fall River in the early 1980s that grew to about 500 members (Marques & Salum, 2007), also called the LusoAmerican Pentecostal Church. Pastor Joel returned to Brazil in 1991 and later returned to the U.S. where he recently died. Today there are several (perhaps 6-9) churches in Massachusetts that were born from this pioneer church.

Several renewal Baptist church groups exist in New England, including the Shalom Baptist International Community in Somerville led by Pr. Jay Moura and the Igreja Communidade Deus Vivo led by Pr. Aloisio Silva.

American Baptist Churches began a new church-planting movement in Boston in 1991 and planted primarily renewal churches (Marques & Salum, 2007). This movement gained force from 2001 to 2004 when about 20 new Brazilian Portuguese churches were planted in Massachusetts and Rhode Island under the New Church Planting Coordination led by Rev. Lilliana DaValle and Pr. Josimar Salum. This forward movement stalled due to issues of church doctrine. Another group of churches that were established with Baptist connections are the Vida Nova churches including Igreja Batista Vida Nova in Medford (Pr. Jose Faria Costa Jr) and Igreja Batista Vida Nova (Pr. Alexandre Silva).

The Southern Baptists also planted many churches since 1995. There are about 30 of these churches in New England, including the Portuguese Baptist Church in Inman Square, Cambridge (Pr. Silvio Santos), the Celebration Church in Saugus (which was in Malden and Charleston under the direction of church planter Pr. Joe Souza), and the First Brazilian Baptist Church of Greater Boston (also known as the Lovely Church) with Pr. Antonio Marques Ferreira.

Assemblies of God

The first Assembly of God churches in Boston were established by Ouriel de Jesus. He was invited by Pr. Alvacir Marcondes to Somerville in 1985, and under his supervision the Assemblies of God denomination in the U.S. experienced tremendous growth. After September of 2001, Pastor de Jesus said he received a message from God to lead a great revival and began holding revival meetings all over the country and world. Currently, he is the pastor of the World Revival Church in Everett, which now has over 70 congregations throughout the U.S. and in 17 other countries with a membership exceeding 15,000.

Despite Pr. Ouriel’s success at leading revivals and church growth movements, his ministry has been accompanied by a great deal of controversy. As a result, in 2002, the church was expelled from the Assemblies of God denomination in both the U.S. and Brazil. The mother church and those he planted are no longer allowed to call themselves Assemblies of God and instead have taken the name The World Revival Church, later adding “Boston Ministries” (Pinto-Maura & Johnson, 2008). These churches continue to exist under Ouriel’s leadership.

There are 36 Brazilian Assemblies of God churches in Massachusetts, including Igreja Vida Assemblies of God (Pr. Salmon Silva) and Mission Assembly of God (Pr. Joel Assis).

Presbyterians

Several Presbyterian churches are in the Boston area. Christ the King church in Cambridge was established in the early 1980s by Pr. Osni Ferreira, who had a multicultural vision. Several additional Brazilian Presbyterian churches have been planted by this church, including New Life Presbyterian (Framingham), Bethel (Marlboro), and Christ the King (East Boston).

Church of Christ

In 1984, the Church of Christ established the Hisportic Christian Mission (HCM) in East Providence, Rhode Island, led by Rev. Wayne Long with the vision to reach Portuguese-speaking people in New England (Hisportic stands for Portuguese as Hispanic stands for Spanish). In 1990/1991 Rev. Aristones Freitas and Josimar Salum planted the first Brazilian Church in Worcester, Mass. Today there are about 46 churches that have been established through the HCM, of which 26 are in Mass., an additional 10 are in other New England states, and three are in Brazil.

Independent churches. The Foursquare Gospel Church arrived in 1991 and now has several churches throughout New England. These include the Communidade Brazileiro of Framingham, PenteBaptist (Pr. Dimitri Grant) and Malden Portuguese Foursquare Church (Pr. Cairo Marques).

Strengths and Opportunities for the Brazilian Churches in Boston and New England

Strengths

The strengths of the Brazilian churches are many. Some churches have numerous young people, many pastors are committed to preaching the Gospel, and large numbers of lay people who fill these churches take seriously their responsibility to know the Bible and to serve Christ. Brazilians as a group are well-accepted in the community. We heard stories which indicate that this is not always true for individuals, particularly with regard to immigration, but we also saw newspaper articles extolling the benefits that Brazilian churches have brought to the community! Brazilian churches can and often do reach out to contribute to their larger communities.

Nevertheless, there are many challenges, including the language barrier, how immigrants can participate in the larger culture and retain their Brazilian culture, immigration issues, and high levels of turnover among church attendees, in part because of immigration. In a series of interviews conducted in 2015, virtually everyone mentioned the challenge of finding affordable meeting space. Many churches do not have their own buildings, and, if they do, they struggle to maintain them. Renting space is increasingly expensive, and there are often problems parking near urban churches. Difficulties surrounding meeting together, an essential aspect of being a church, results in significant stress in the community.

These churches have other struggles as well. Converting new people to Christ is often hard. There is a need to raise up new pastors, because many pastors have been in the U.S. for several decades. It can be difficult to recruit young people to such a challenging ministry and one focused specifically on the Brazilian community.

Some challenges come from outside the churches and others from within. Networking among Brazilian pastors is challenging even though there are some groups that meet regularly, including BMNET (Brazilian Ministers Network), Brazilian Prayer Network of Boston, and Pastors Fraternal Union in Fall River. When asked during an interview to name the single thing that would be most helpful to them, pastors frequently said that they would like better contact with other Brazilian pastors. Nevertheless, multiple factors can limit opportunities for networking:

- Journeyman pastors work a full-time job in addition to pastoring and lack time for networking.

- Instability in church membership as members return to Brazil contributes to pastor overload and burnout.

- Pastors may compete among themselves for church members.

- The needs of first, second, and third generation immigrants are difficult to navigate. For example, churches struggle with whether to have services in English or maintain evening services as in Brazil versus the American way of holding morning services.

Opportunities

The opportunities for growth and change are many. Among them are these:

The Brazilian population in Massachusetts is estimated by the 2005 census to be approximately 84,000 individuals, many of whom are not in church. There is great potential for church growth within (and outside) the Brazilian population.

Brazilian churches can get more involved with the local and global realities, e.g., by supporting other church efforts such as limiting human trafficking.

They can perhaps better educate their members about the problems with the prosperity gospel, and the financial abuses that are too often perpetrated against church members (including the Ponzi scheme called Telex Free in which some pastors participated).

They need to strategize for the future, as more and more of their members speak English and either ask for changes in Brazilian churches, or leave for English-speaking churches.

The Brazilian churches have much to teach the larger community. Church planting appears to be a primary focus for Brazilian Christians and virtually every church visited had either already engaged in church planting or hoped to at some point. Many churches also feel called to send out missionaries. Even though we were unable to get an estimate of the number of missionaries commissioned, anecdotal evidence suggests that there are surprisingly many missionaries from these churches. And finally, at least one of these churches feels called to minister not just in their local community but around the world. In a church community that was itself not financially flush, the church has supported orphanages in Brazil and dug a much needed well in a needy community without a church, while also supporting ministries in Africa. This level of commitment is remarkable and challenging to mainstream American churches.

In conclusion, the size, energy, number of young people, and commitment to church growth in Brazilian churches should inspire the Global Church. The needs are great, and the opportunities are many for serving those engaged in these impressive churches and for ministering together in the larger community.

Endnotes

*Johnson and Zurlo (2016) report approximately 76% Catholics and 28% Protestant. These numbers refer to the percentage of all Brazilians and demonstrate that some Brazilians claim dual affiliation or membership in more than one community of believers. By their estimate, the number of dually affiliated believers is 13% of Brazilians, many of whom claim to be both Protestant and Catholic. Their estimate is based on an effort to provide a more precise estimate than the 2010 census, in part by collecting information from additional sources than the census and in part by allowing individuals to report belonging to more than one religion.

**The remaining three churches are the Assemblies of God, the Four-Square Church, and the Christian Congregation (Freston, 1999).

References

Boston Redevelopment Authority. (2012). New Bostonians 2012. BRA Research Division Analysis.

Chesnut, R. A. (1997). Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom in Brazil: The Pentecostal Book and the Pathogens of Poverty. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Freston, Pl. (Jan-Mar, 1999). “Neo-Pentecostalism in Brazil: Problems of Definition and the Struggle for Hegemony.” Archives de sciences sociales des religions. 44E, No 105, p. 145-162.

IBGE (Institute Brazileiro de Geografia e Estatistica) (2010). Census. http://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/en/ censo-2010 Accessed 6.27.2015.

Johnson, T. M., & Zurlo, G. A. (Eds.) (2016) World Christian Database. Leiden/Boston: Brill. Accessed at worldchristiandatabase.org/wcd on 1 January 2016.

Juergensmeyer, M., & Roof, W. C. (Eds.) (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Marques, C., & Salum, J. (2007). The Church among Brazilians in New England. In R. Mitchell & B. Corcoran (Eds.), New England’s Book of Acts. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Pew Research Center (2013). Brazil’s Changing Religious Landscape. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/07/18/brazils-changing-religious-landscape/ Accessed 6.28.2015.

Pinto-Maura, R., & Johnson, R. (2008). Abused God. Maitland FL: Xulon Press.

U.S. Census (2009). ActivitiesUpdate_June09. Accessed on 8.2.2015 from http:// www.henrietta.org/index.php/doccenter/2010-us-census-documents/6-june-2009-census-2010-activities-update/file

This essay updates the story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston as told in New England’s Book of Acts (2007), originally published by the Emmanuel Gospel Center in preparation for the October 2007 Intercultural Leadership Consultation. The earlier version was written by Cairo Marques and Josimar Salum, and work on the current document began by talking with them as well as 45 other Brazilian pastors and lay people in the Greater Boston community. Their observations are integrated into the comments above. —Kaye Cook and Sharon Ketcham, February 24, 2016.

__________

See the original 2007 article on the origins of the Brazilian church movement in New England in New England’s Book of Acts.

Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

This summary of a larger study offers both story and statistics on life and culture in one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the area, the study offers data on racial trends, economy, housing, education and more.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 91 — July-August 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, managing editor

Neighborhood studies reveal dynamics and principles which reflect the unique shape—culturally, geographically, and socially, for example—of a given place. By highlighting neighborhood-specific histories, heroes, and innovations, we can add story to statistics, and help complement, interrelate, and animate data in ways that better inform and inspire the development of community responses to community challenges. The Emmanuel Gospel Center has produced various neighborhood studies to this end. In recent years, we have supported the Youth Violence Systems Project by conducting research on a half dozen neighborhoods that are known to have had a history of youth violence. These studies help provide a wider framework for viewing each neighborhood as they touch on many aspects of what makes that particular neighborhood unique.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition (2013) offers both story and statistics on many facets of life in this one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the immediate area, the study offers data on racial trends; facts about the current population including, for example, the breakdown of ages of the residents and how they compare with other areas; and facts about the economy, housing, and education. There are also updated, annotated directories of the neighborhood’s churches, schools, and agencies including those agencies particularly concerned with violence prevention and public safety. Fourteen tables, nine new graphs designed by Jonathan Parker, four maps, over a dozen images, and an extensive bibliography help tell the story.

In this issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, we offer excerpts from the Grove Hall study with bullet points and graphics. The complete report can be viewed or downloaded HERE as a pdf file.

Understanding the Grove Hall Neighborhood

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center

About the Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

Continuing in its commitment to foster stronger communication, agreement, and cooperation around a community-wide response to youth violence in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) has recently released an updated research study on Boston’s Grove Hall neighborhood.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition, copyright © 2013 Emmanuel Gospel Center, was written and researched by Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher at EGC, and produced by the Youth Violence Systems Project, a partnership between EGC and the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. A first edition was released in 2009 and titled Grove Hall Neighborhood Briefing Document. As the first edition was produced prior to the 2010 U.S. Census, much of the information was based on the 2000 Census. By returning to Grove Hall now, not only is EGC able to study the latest numbers, but changes over the past decade may indicate either new concerns or evidences of progress.

This neighborhood study is one of six Boston neighborhood studies. The others in this series are: Uphams Corner (2008), Bowdoin-Geneva (2009), South End & Lower Roxbury (2009), Greater Dudley (2010), and Morton-Norfolk (2010).

These studies were produced as part of the Youth Violence Systems Project. Two important results of the Project are a new framework for understanding youth violence and an innovative computer model. Both of these were designed in and for Boston to enable a higher quality of dialogue around understanding and evaluating the effectiveness of youth violence intervention strategies among a wide range of stakeholders, from neighborhood youth to policy makers.

Report Overview

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition, presents thoughtful information on many facets of life in this Roxbury neighborhood. Following a history of the immediate area, the study offers data on racial trends; facts about the current population including, for example, the breakdown of ages of the residents and how they compare with other areas; and facts about the economy, housing, and education. There are also updated, annotated directories of the neighborhood’s churches, schools, and agencies including those agencies particularly concerned with violence prevention and public safety. Fourteen tables, nine new graphs designed by Jonathan Parker, four maps, over a dozen images, and an extensive bibliography help tell the story.

Neighborhood History

The first 200 years of settlement (1650-1850) was characterized by farms, summer estates, and orchards, including, in 1832, the estate of horticulturalist Marshall P. Wilder who used the land to experiment with many varieties of fruit trees, plants and flowers. The name “Grove Hall” is derived from the name of another estate and mansion owned by Thomas Kilby Jones, a Boston merchant who developed the property around 1800. That estate dominated the Grove Hall crossroads for a century and later served the community for many years as a health center. The growth and decline of New England’s largest Jewish community centered in this neighborhood is documented as the most important facet of the neighborhood’s history between 1906 and 1966, and the Mothers for Adequate Welfare protests and subsequent riot of 1967 were pivotal events that had an enduring and significant impact on the neighborhood. Although, in recent years, the neighborhood has faced problems and violence, its history can generally be characterized by revitalization and economic development. This 13-page history is offered because it is valuable to understand the people and groups who built Grove Hall and helped shape its current identity.

Boundaries

The center of Grove Hall is commonly understood to be the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue with Washington Street and Warren Street. For the purposes of this study, Grove Hall is defined as the neighborhood which includes the area of the five U.S. Census tracts that surround that central crossroads. These five census tracts are 820, 821, 901, 902, and 903.

What follows is a list of the major topics covered in the study, with a few bullet points highlighting some of the facts uncovered.

Racial and Ethnic Trends

During the last decade, the number of Hispanics in this area increased from 3,414 to 5,171, an increase of over 50%, representing an increase from 20% to almost 30% of the entire population.

While the area has a Black or African American majority, the overall percentage of people in this area who are Black decreased from 73% to 64% since 2000.

Linguistic Isolation

Linguistic isolation refers to households where no one 14 and older speaks English very well, therefore facing social and economic challenges. Households in Grove Hall are more likely to be linguistically isolated than households across the nation and households across the state. Approximately 15.2% of households in Grove Hall are linguistically isolated.

Age Characteristics

Regarding age characteristics, the study shows that Grove Hall has a significantly higher percentage of young people than the city of Boston as a whole, as well as the state and nation. The area has 5,450 youth under the age of 18 years, who represent 30.6% of the total neighborhood population, compared with 16.8% in the city, 21.7% in the state, and 24% in the nation.

The number of youth between the ages of 12 and 18 in Grove Hall is 2,243 or 12.6% of the population, compared to only 7.5% in this age group for Boston overall.

Population Trends

After a steady decline in population from 1940 when the population was 30,307 to the year 2000 when there were 16,771 residents, the 2010 census shows an increase with a 6% climb over the past ten years to 17,823.

Family Structure

In Grove Hall, 71.9% of families with children under 18 are headed by single females and 7.2% are led by single men. Only about 21% of Grove Hall families with children under 18 have two parents present.

Single parent families with children under 18 in Grove Hall represent the majority of all families, 79%, compared with the national percentage of 34%, the state percentage of 32%, and the city of Boston percentage of 53%.

Economy and Poverty

The percent of people below the poverty level in Grove Hall is much higher than the city of Boston as a whole. The average of the percentages of people in poverty in each of the five census tracts is 37% compared to the city of Boston’s rate of 21%, the state’s rate of 10.5% and the national rate of 13.8%.

For youth and children under 18, 73.1% were under the poverty level in census tract 903 and 56.1% in census tract 902. This compares with 28.8% in the city of Boston overall and 13.2% for the state.

Public Assistance

There is a higher percentage of households receiving public assistance in Grove Hall than in the city, the state, and the nation. Since 2000, the number and percentage of households receiving public assistance has increased in four of the five census tracts. The Grove Hall census tract with the highest percentage of households receiving public assistance is census tract 903 with 21.7%.

Housing

Across the U.S., 65.1% of housing units are owner-occupied and 34.9% are renter-occupied. In Boston, 33.9% of all housing is owner-occupied, roughly half the national average. However, in Grove Hall, only 18.8% of the housing units are owner-occupied (1,274), while 81.2% are renter-occupied (5,495).

Education and Schools

Residents of Grove Hall have a lower level of educational attainment than the population of Boston, the state, or the nation. The percentage of people in Grove Hall with a bachelor’s degree or higher is only about 1/3 the percentage of the city or the state, and about 1/2 the national percentage.

More than one quarter of the residents of Grove Hall have not graduated from high school, whereas statewide, only 11% are not high school graduates. In census tract 901, over 32% of the population has not graduated from high school.

The Burke High School had only a 43.4% four-year graduation rate, one of the lowest in the city. This falls far below the overall Boston Public School four-year graduation rate of 64.4%. The Burke High School also had a very high dropout rate of 33.7% compared to 15.1% for Boston (in 2011).

To learn more about Grove Hall, read a Harvard University report here: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/content/download/68818/1248082/version/1/file/hotc_finalreport.pdf.

To view or download the complete Grove Hill Neighborhood Study, from which this article is derived, click HERE.

Bibliography

Barnicle, Mike. “A Street Forgotten.” Boston Globe, 1 April 1987, 17.

Billson, Janet Mancini. Pathways to Manhood: Young Black Males Struggle for Identity. Expanded 2nd edition. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1996. Billson studies five young boys who grew up in Roxbury in the late 60s and early 70s.

“Blue Hill Avenue: Progress, 1993-2003.” City of Boston, Dept. of Neighborhood Development. www. cityofboston.gov/dnd/pdfs/BHA_Map_3FLAT.pdf (accessed 15 June 2009).

Boston Globe, June 2-June 6, 1967. Various articles on the Blue Hill Avenue Riots.

The Boston Plan: Revitalization of a Distressed Area: Blue Hill Avenue. Boston: City of Boston, 1987.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. The Blue Hill Avenue Corridor: A Progress Report and Guidelines for the Future. Boston: B.R.A., 1979.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. City of Boston Zip Code Area Series, Roxbury/Grove Hall, 02121, 1990 Population and Housing Tables, U.S. Census. Boston: B.R.A., 1994.

Boston Redevelopment Authority. Roxbury Strategic Master Plan. Boston: B.R.A., 2004 ( January 15). While not specifically on Grove Hall, the Master Plan is important for its overall vision and impact, which will affect Grove Hall. See www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org.

Cooper, Kenneth J. “Blue Hill Avenue: A Dream Gathers Dust; 4 Years Later, Business, Housing and Transit Plans Haven’t Happened.” Boston Globe, 22 October 1981, 1.

Cullen, Kevin, and Tom Coakley. “A Month of Fear and Bullets.” Boston Globe, 5 November 1989, 1.

Cullis, Charles. History of the Consumptives’ Home and Other Institutions Connected with a Work of Faith. Boston: A. Williams, 1869. About the Cullis Consumptives’ Home at Grove Hall.

D.A.R. Roxbury Chapter. Glimpses of Early Roxbury. Boston: Merrymount Press, 1905.

Drake, Francis Samuel. The Town of Roxbury. Boston: Municipal Print Office, 1908.

Fields, Michael. “Blacks in a Changing America; Wrights of Roxbury: A Family Making It.” Boston Globe, 28 June 1982, 1.

“Freedom House: A Legacy Preserved,” Northeastern University Library Archives, www.lib.neu.edu/archives/freedom_house/team.htm (accessed 1 June 2009).

French, Desiree. “Revitalization Gets Serious at Grove Hall: A $7.8 Million Program Formed to Aid Roxbury Business District.” Boston Globe, 26 March 1988, 41.

Gamm, Gerald. Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. This book has maps showing trends and changes in Jewish and African American settlement, median rent trends, and locations of institutions.

Gordon, Edward W. Boston Landmarks Survey of Dorchester: Grove Hall, 1995. www.dorchesteratheneum.org/page.php?id=622 (accessed 18 May 2009).

“Grove Hall,” Heart of the City, Harvard University (original page missing, but see: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/content/download/68818/1248082/version/1/file/hotc_finalreport.pdf for what appears to be a similar report at the Kennedy School of Government. Search document for “Grove Hall.” Includes information on conditions, context, history, social issues, planning, processes, testimonies, organizations and specific places.

Hayden, Robert C. Faith, Culture and Leadership: A History of the Black Church in Boston. Boston: Boston Branch NAACP, 1983.

Hentoff, Nat. Boston Boy: Growing Up With Jazz and Other Rebellious Passions. Philadelphia: Paul Dry books, 2001 (originally published 1986). Henthoff was born in the Grove Hall neighborhood in 1925, and in this memoir gives a vivid account of growing up in the Jewish community of the 1930s and 1940s.

Levine, Hillel, and Lawrence Harmon. The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions, pb. edition. New York: The Free Press, 1993. While Levine and Harmon’s book gives many insights and details about life, religion, and politics in the Jewish community in the area, its analysis of the causes of its decline has been challenged and shown to be inadequate by Gerald Gamm in Urban Exodus.

Pasquale, Ron. “Grove Hall’s Renaissance; New Development Caps Hub Area’s Revival as a Commercial Mecca.” Boston Globe, 10 February 2007, E-23.

Project RIGHT, Boston Ten Point Coalition, Health Resources in Action, and the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center. Connecting the Disconnected: A Survey of Youth and Young Adults in Grove Hall. Boston: City of Boston, 2010. A survey and report on out-of-work and out-of-school young adults ages 16-24 in Grove Hall.