BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Inner Life Of A Leader [Resource List]

Resources On The Inner Life Of A Leader

Inner Life Of A Leader [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Barton, Ruth Haley. Strengthening the Soul of Your Leadership: Seeking God in the Crucible of Ministry. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2008.

Blanchard, Ken, and Phil Hodges. Lead Like Jesus: Lessons from the Greatest Leadership Role Model of All Time. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson, 2005.

Clinton, J. Robert. The Making of a Leader: Recognizing the Lessons and Stages of Leadership Development. Revised and updated Edition. Colorado Springs, Col.: NavPress, 2012.

Detrick, Jodi. The Jesus-Hearted Woman: 10 Leadership Qualities for Enduring and Endearing Influence. Springfield, Missouri: Salubris Resources, 2015.

Fryling, Robert A. The Leadership Ellipse: Shaping How We Lead by Who We Are, Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2010.

Harney, Kevin G. Leadership from the Inside Out: Examining the Inner Life of a Healthy Church Leader. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2007.

Howell, Don N., Jr. Servants of the Servant: A Biblical Theology of Leadership. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2003.

Malphurs, Aubrey. Being Leaders: The Nature of Authentic Christian Leadership. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2003.

Maxwell, John C. Developing the Leader Within You. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson, 2000. Maxwell has also written many other books on leadership.

Sanders, J. Oswald. Spiritual Leadership: A Commitment to Excellence for Every Believer. Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2007.

Scazzero, Peter. The Emotionally Healthy Leader: How Transforming Your Inner Life Will Deeply Transform Your Church, Team, and the World. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2015.

Stowell, Joseph M. Redefining Leadership: Character-Driven Habits of Effective Leaders. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2014.

You May Also Like

Intercultural Leadership [Resource List]

Resources On Intercultural Leadership

Intercultural Leadership [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Branson, Mark Lau, and Juan F. Martinez. Churches, Cultures and Leadership: A Practical Theology of Congregations and Ethnicities. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011.

DeYmaz, Mark, and Harry Li. Leading a Healthy Multi-Ethnic Church: Seven Common Challenges and How to Overcome Them. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2013.

Plueddemann, Jim. Leading Across Cultures: Effective Ministry and Mission in the Global Church. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2009.

You May Also Like

Modern Classics on Leadership [Resource List]

Resources On Leadership - Modern Classics

Modern Classics on Leadership [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Leadership strategies can shift with culture. But some modern texts have withstood the test of time, and are still relevant a generation later. Below are some leadership books from before the year 2000 that I believe are worth a fresh look.

Damazio, Frank. The Making of a Leader. Portland, Ore.: City Christian Publishing, 1988.

Ford, Leighton. Transforming Leadership: Jesus' Way of Creating Vision, Shaping Values & Empowering Change. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1991.

Nouwen, Henri J. M. In the Name of Jesus: Reflections on Christian Leadership. Chestnut Ridge, New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1989.

Peterson, Eugene. Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1992.

Peterson, Eugene. Working the Angles: The Shape of Pastoral Integrity. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1987.

Peterson, Eugene. Under the Unpredictable Plant: An Exploration in Vocational Holiness. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1992.

Peterson, Eugene. The Contemplative Pastor: Returning to the Art of Spiritual Direction. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1993.

White, John. Excellence in Leadership: Reaching Goals with Prayer, Courage and Determination. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1986.

You May Also Like

Women In Christian Leadership [Resource List]

Resources On Pastoral Leadership

Women In Christian Leadership [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Detrick, Jodi. The Jesus-Hearted Woman: 10 Leadership Qualities for Enduring and Endearing Influence. Springfield, Missouri: Salubris Resources, 2015.

Scott, Haylee Gray. Dare Mighty Things: Mapping the Challenges of Leadership for Christian Women. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2014.

Surratt, Sherry, and Jenni Catron. Just Lead!: A No Whining, No Complaining, No Nonsense Practical Guide for Women Leaders in the Church. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013.

Pastoral Leadership [Resource List]

Resources On Pastoral Leadership

Pastoral Leadership [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Barton, Ruth Haley. Strengthening the Soul of Your Leadership: Seeking God in the Crucible of Ministry. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2008.

Beeley, Christopher A. Leading God’s People: Wisdom from the Early Church for Today. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2012.

Blackaby, Henry, and Richard Blackaby. Spiritual Leadership: Moving People on to God's Agenda. Revised and Expanded edition. Nashville, Tenn.: B&H Books, 2011.

DeYmaz, Mark, and Harry Li. Leading a Healthy Multi-Ethnic Church: Seven Common Challenges and How to Overcome Them. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2013.

Harney, Kevin G. Leadership from the Inside Out: Examining the Inner Life of a Healthy Church Leader. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2007.

Hybels, Bill. Courageous Leadership: Field-Tested Strategy for the 360° Leader. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2002.

Malphurs, Aubrey, and Will Mancini. Building Leaders: Blueprints for Developing Leadership at Every Level of Your Church. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2004.

Plueddemann, Jim. Leading Across Cultures: Effective Ministry and Mission in the Global Church. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2009.

Scazzero, Peter. The Emotionally Healthy Leader: How Transforming Your Inner Life Will Deeply Transform Your Church, Team, and the World. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2015.

Surratt, Sherry, and Jenni Catron. Just Lead!: A No Whining, No Complaining, No Nonsense Practical Guide for Women Leaders in the Church. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013.

You May Also Like

Leadership Strategies & Models [Resource List]

Resources On Leadership Strategies & Models

Leadership Strategies & Models [Resource List]

by Rudy Mitchell

Banks, Robert J., Bernice M. Ledbetter, and David C. Greenhalgh. Reviewing Leadership: A Christian Evaluation of Current Approaches. 2nd edition. Engaging Culture Series. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books Academic, 2016.

Beeley, Christopher A. Leading God’s People: Wisdom from the Early Church for Today. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2012.

Hybels, Bill. Courageous Leadership: Field-Tested Strategy for the 360° Leader. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2002.

Malphurs, Aubrey, and Will Mancini. Building Leaders: Blueprints for Developing Leadership at Every Level of Your Church. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2004.

Scott, Haylee Gray. Dare Mighty Things: Mapping the Challenges of Leadership for Christian Women. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2014.

Stott, John. Basic Christian Leadership: Biblical Models of Church, Gospel and Ministry. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2002.

You May Also Like

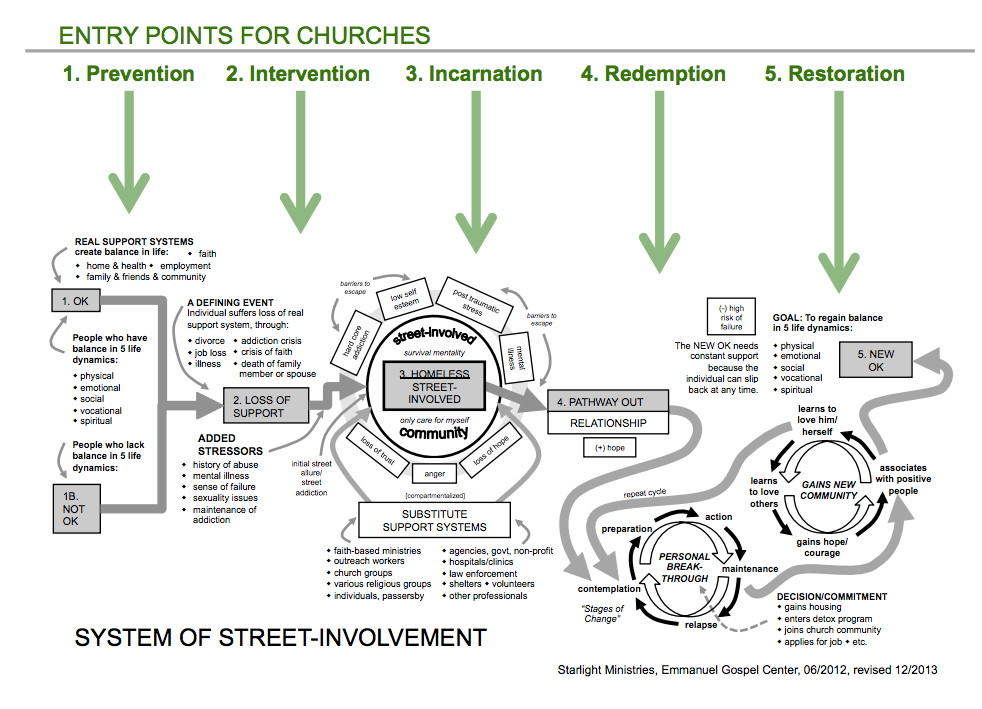

5 Entry Points for Churches to Address Homelessness

Addressing homelessness effectively can surprise our intuition. Learn about entry points from those who study homelessness as a system.

5 Entry Points for Churches to Address Homelessness

by EGC Starlight Ministries

Since 1990, Starlight Ministries has equipped individuals to build life-changing relationships with people affected by homelessness. Starlight trains individuals and groups in classroom settings as well as hands-on ministry venues. These opportunities provide the Church and those struggling with homelessness with effective tools for building communities where all can experience personal transformation through Jesus Christ.

Street Involvement As A System [infographic]

Homelessness is a complex system. Learn about this system and how the church can engage.

Choosing to Listen

EGC Executive Director Jeff Bass reflects on the greatest lesson from the recent meeting of the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization at the Boston Islamic Center, attended by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Mayor Marty Walsh.

Last night I attended a community meeting at the Boston Islamic Center in Roxbury Crossing. Over 2,600 people came together in my neighborhood to hear Mayor Walsh, Senator Warren, and assorted leaders and citizens from the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization challenge us to stand together against bigotry and for community.

“It would be arrogant and naïve for me to continue to ignore my own arrogance and naïveté as I process this. So what do I do now?”

Like many in Boston’s blue bubble, I was shocked and deeply disappointed by the results of the November election, and I’ve spent the last few weeks trying to get a handle on our new and emerging reality. I have been asking myself, “What was I missing?” It would be arrogant and naïve for me to continue to ignore my own arrogance and naïveté as I process this. So what do I do now?

As I heard speaker after speaker affirm last night, my first responsibility is to listen. As a White Evangelical male organizational leader, growing in listening is especially important for me.

I know many people who are angry, and many who are fearful—not just about the divisiveness in our country, but about the impact the election will have (and is having) on their families and neighborhoods. One friend wrote that she feels like someone is pointing a gun at her children saying, “Don’t worry, I won’t pull the trigger.” Even though the gun is not pointed at me in the same way, can I appreciate the danger that she and so many others are experiencing? Can I begin to understand the pain and betrayal they feel?

At the same time, I know people who are hopeful—even excited—about a change in leadership and the opportunity for the country to move in what they see as a new direction. They had a different set of “deal-breakers” in the election (change, the economy, the Supreme Court perhaps). Can I understand their views, and appreciate their decisions? Can I empathize with the pain they’ve felt these last eight years that would lead them to choose Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton? It’s unfathomable to me, yet look at what happened.

“Even though the gun is not pointed at me in the same way, can I appreciate the danger that she and so many others are experiencing? Can I begin to understand the pain and betrayal they feel?”

So I have a lot to learn, and I’m going to start by doubling down on listening. Well. And a lot. This means taking the time for more conversations, more reading, and more pressing into new relationships. And when I do, I want to seek first to understand, feel, relate as best I can, before I say or do anything else.

“I want to first seek to understand, feel, relate as best I can, before I say or do anything else.”

As we create space at EGC staff members to speak up with our perspectives on what we are learning and seeing in the church in Greater Boston, and as we weigh in on issues that affect us, I hope that we can stay grounded in listening.

If you’d like to talk about any of this, please let me know. I’d love to listen.

Jeff Bass and his wife Ellen live in Roxbury Crossing, about a mile from the Islamic Center.

Dominance in Leadership: What I'm Learning

Dominance in leadership is common in America today. But is it healthy for Christian leaders? Jess Mason shares personal experience and reflections on biblical perspectives of dominance in leadership.

Dominance in Leadership: What I'm Learning

by Jessica Mason

“I’m just not cut out to be a leader.”

My pastor at the time grinned with a twinkle in his eye and asked, “Why do you say that?”

I argued, “Because I’m not good at cutting people off at the knees to stay the center of attention.” He tried to tell me, That dubious “skill” is not what godly leadership is about. I’ve tried to believe him.

As part of our series on conflicting cultural ideals, I'm investigating what the Bible has to say about common ideals that society imposes on leaders and on women. In this post I spotlight the often unspoken cultural ideal that effective leaders are dominant.

My search begins with a well-known passage where Jesus coaches his disciples that, while Gentile rulers “lord it over” others, it should not be so with them. Following the trail of the Greek word for “lord it over” (katakurieuw and kurieuw) around the Bible, I discovered the first mention of “lording over” at the fall of Adam and Eve. A relationship of dominance is apparently part of the Curse—a consequence of sin—not part of God’s beautiful design.

Accordingly, Jesus, Paul, and Peter each taught against leading through dominance. Whenever the Bible mentions humans taking it upon themselves to lord over other humans, the context is never positive.

“I’ve been conflicted about my occasional ability to dominate—it feels wrong when it happens, but when I can’t make it happen I see it as evidence that I am not cut out to lead.”

Recently I encountered a rather narcissistic individual. Narcissists have a pathological need for constant positive attention and adulation. I became increasingly agitated with this individual’s persistence in dominating the conversation and keeping themselves and their accomplishments in focus, to the detriment of meaningful action or decision making.

Reflecting on the experience, I flashed back to leadership roles in my past and came to a startling revelation—in many of my leadership experiences, I managed to center the situation around my thoughts or initiative, hold people in thrall, or get away with doing 75% of the talking. I'd confused leadership with narcissistic behaviors!

I’ve been conflicted about my occasional ability to dominate—it feels wrong when it happens, but when I can’t make it happen I see it as evidence that I'm not cut out to lead. I've repeatedly been disappointed with how my leadership eventually ends up feeling like The Jess Mason Show.

I’m waking up to the realization that, if godly leadership has nothing to do with the ability to dominate, apparently I've failed to understand in my bones what leading others well truly looks like. In my observation, dominance can co-occur with real leadership. Furthermore, people can mistake dominance for leadership and will follow dominators—even to their own detriment—in the absence of a true leader. But I now believe that a dominant personality is actually irrelevant to healthy leadership.

I’m not in a leadership role at the moment. That buys me some time to learn. How can I hope to discern whether I’m called to lead others again until I understand what leadership is? I’d like to share with you what I’m learning, from the Bible and from living example.

“People can mistake dominance for leadership and will follow dominators—even to their own detriment—in the absence of a true leader.”

I’d like to return to the starting point of my search—Jesus and his disciples. This humble master clarifies that leaders should think of themselves as the servant of those they lead.

I take this to mean that while we usually think of leaders as “having” followers, Jesus turns this on its head. Instead he says that leaders should devote themselves to a vigilance for the good of those they lead, the way servants attend to their master’s good.

“Leaders should devote themselves to a vigilance for the good of those they lead.”

When Paul rejects dominance in leadership, he advocates that leaders instead should “work alongside others for their joy.” In contrast to the narcissist’s goal of using followers to supply them with positive attention, the true leader’s goal is to prompt others to deeper joy in God as a result of the leader’s partnership with them.

Peter also wrote to church leaders that instead of dominating their flocks, they should lead by example. This implies that an effective leader prioritizes personal obedience and discipleship over reprimand and force. In other words, she puts the lion’s share of her fervor into practicing what she preaches.

What strikes me about these biblical qualities for leadership is that they’re not inherently competitive. There can be more than one person in a group that exhibits these qualities. Not so with dominance, where There Can Be Only One. Biblical leadership includes. It collaborates.

“In contrast to the narcissist’s goal of using followers to supply them with positive attention, the true leader’s goal is to prompt others to deeper joy in God as a result of the leader’s partnership with them.”

I would like to give a shout-out to my supervisor, Stacie Mickelson, for the ways she models godly leadership to me. As my supervisor, she regularly and concretely protects the interests of my healthy functioning on the Woven team. She listens well and dislodges obstacles. She balances my commitments and attends to my professional development. She also follows through on details like making sure my office chair isn’t hurting my back.

In the team setting, Stacie leads meetings as though she’s working with friends and partners, not enemies to conquer or schlubs to drag along. In meetings she leads, even if she brings a clear agenda, I don’t get the sense she's forcing or dominating. Instead I find each of us heard and valued, as she shepherds the conversation towards healthy action.

RESPOND

Meet Your Obstacles

In your leadership context today, identify what if any obstacles you would have to overcome to (a) think of yourself as a servant, (b) lead by example, or (c) throw your lot in as a fellow worker with those you lead.

Share your obstacles with a fellow leader. What is the Holy Spirit saying to you through your conversation, the Scriptures, or your prayer? What step of faith is the Holy Spirit inviting you to take next?

Encourage a Woman Leader

Think of a Christian woman leader that you know who leads by (a) positive example, (b) a servant’s heart, or (c) working alongside others for their joy.

Tell her today in person, in a note, or in a text, what you appreciate about her example of Christian leadership. If you have the platform, with her permission, share publicly what you appreciate about her leadership that others might learn from. Pray for her continued effectiveness as a leader in her setting.

Pray for Our Leaders

Think of a leader—either someone you know or a public figure—who seems to lead primarily by dominance.

First, see that person as a human being, created in the image of God. Pray that the Holy Spirit would work in her/his heart to create in them a desire to serve others and work alongside them for the good of all.

Jessica Mason is a licensed minister, spiritual director, and research associate in Applied Research & Consulting at EGC. Her passion is to see God’s goodness revealed to and through Christian leaders and pillars in the Boston area.

The Awkward Dance: Christian Women Leaders Find Footing Amid Conflicts of Ideals

When you think good Christian woman, to what extent do you think effective leader? In this post we explore six conflicts-of-ideals reported by participants at the Woven Consultation on Christian women in leadership in March 2016.

The Awkward Dance: Christian Women Leaders Find Footing Amid Conflicts of Ideals

by Jess Mason

When you think, “good Christian woman,” to what extent do you think, “effective leader?”

According to our research, Christian women leaders face conflicting ideals for women and for leaders in their communities, such that traits of effective leaders can contradict traits of admirable Christian women.

I believe that if these cultural ideals go unexamined, capable women may falsely doubt their fitness for leadership. They may also betray their leadership strengths—as well as their authentic selves—in order to conform to their culture’s image of a skilled leader.

In this post we explore six conflicts-of-ideals reported by participants at the Woven Consultation on Christian women in leadership in March 2016. In a series of follow-up posts in the coming months, we’ll look at these conflicts and consider: Where are these cultural ideals challenged by Scripture? Where do biblical examples shift—or broaden—the picture of what healthy leadership and/or healthy womanhood can look like?

THE LEADER-WOMAN DANCE

Conflicting ideals for leaders and women seem to begin in many cases with masculinized norms for leadership. One woman shared this challenge in terms of available role models: “Being shaped by male dominated fields, I don’t know [how] to lead being [a] woman.” Another woman reported, “In ministry, I’ve experienced that I had to be or act different than my true self as a woman because I had to act as a man.”

The Bible challenges the assumption that effective leaders must be men. Women in formal leadership roles include Deborah the judge, Junia the apostle, and Phoebe the deacon, among others. Women of extraordinary influence without official leadership roles include Esther, who planned and made an appeal to prevent an Israelite genocide, and Abigail, who confronted a battalion to lead David back to God’s word and will, setting the tone (and providing the land base) for David’s unparalleled reign over Israel.

To lead wholeheartedly, women leaders need to be set free from contradictory standards. As one Woven participant put it, “We need to be able to lead as women, not be shoehorned into leading like men.” Here are the cultural contradictions women leaders report navigating in their leadership settings.

SIX CONFLICTING IDEALS FOR LEADERS VS. WOMEN

1. Should I be dominant/aggressive or accommodating?

American culture can prize dominance in male leaders, sometimes to a blinding degree. One woman mentioned a “dominating male” ideal for leadership. Another observed, “Women need to be more aggressive…to compete with their male counterparts in business.”

But leaders must change their tune to be considered admirable women: “Being an alpha female is…too manly.” One woman shared that, “Women can’t be aggressive in advocating for themselves.” Multiple leaders reported that the more common expectation on women is that they “be available” and “meet everyone’s expectations.”

2. Should I be direct/assertive or agreeable?

One minister shared that over her years in leadership she has had to force herself to be more “direct” than she feels comfortable being as a woman. Others affirmed this tension: “Women aren’t assertive.” “It is hard to confront people.” “It's not feminine to disagree.”

3. Should I be confident or self-effacing?

Many women reported feeling that leaders are supposed to appear strong and put-together at all times, and not show weakness or vulnerability. The expected appearance of strength led one leader to lament, a “leader must be always confident. I’m not always confident.” In fact, the very opposite of confidence may be expected of women: “I must present myself as ‘less-than’ to be liked.”

4. Should I be hard or nice?

Like the 19th century children’s nursery rhyme—sugar and spice and everything nice, that’s what little girls are made of—women are expected to be “always happy and positive all the time.” Bottom line: “Women should be nice.”

But one woman shared the expectation that as a leader, “it’s better to be hard than vulnerable.” Another shared that she felt the need to come across as “hard” to be effective in her leadership context, even though “that’s not my true self.”

5. Should I be decisive or consensus-building?

While women agreed there are different types of leadership, some felt forced to choose between false opposites. One wrote that leadership tends to be narrowly defined by those already in power, with principles like, “good leaders are decisive, not consensus building.”

One leader felt she had to decide between being a “good decision-maker” and being a “follower, as expected [of women] from a cultural and social perspective.”

6. Should I be unemotional or emotional?

A common tension for women in leadership is the scope and extent to which emotions and emotional expression have a role in effective leadership. One woman shared that she hears the message that women are supposed to be “giving and emotional.” Another wrote, “women are the weaker/emotional/vulnerable gender.” But, as previously stated, leaders are expected not to show vulnerability.

Without the acknowledgement of emotions as a potential source of insight, the expected emotionality in women would appear to do nothing more than cripple effective leadership.

RESPOND

Tell Us What You Think

We hope this article fosters discussion, reflection, and greater awareness of your leadership choices in your various work and life settings. Please join the Facebook discussion to add your thoughts and experiences.

Share Your Story

Have you experienced any part of this awkward dance in your community? Or does your community have some wisdom you’d like to share? If you have a fuller story to share, contact Jess Mason at jmason [at] egc.org about contributing a personal reflection blog post.

What Else Should WOVEN Be Discussing?

Is there a part of the leader-woman dance that was not mentioned that you would like to bring to our attention? Contact Jess Mason at jmason [at] egc.org to share your insights.

Jess Mason is a licensed minister, spiritual director, and research associate in ARC@EGC. Her passion is to see God’s goodness revealed to and through Christian leaders and pillars in the Boston area.

About the Melnea Cass Network

MCN believes that youth can thrive and overcome the systemic problems of their environment if they have a network of social support that addresses physical, vocational, social and spiritual needs. The MCN is working to convene local leaders for shared learning and collaborative action towards that common purpose. MCN's mission is "ending youth poverty and violence one neighborhood at a time."

Melnea Cass Network—Committed to ending youth poverty and violence one neighborhood at a time.

The Melnea Cass Network is named in loving memory of the tireless South End/Lower Roxbury community and civil rights activist Melnea Cass (1896-1978).

MCN believes that youth can thrive and overcome the systemic problems of their environment if they have a network of social support that addresses physical, vocational, social and spiritual needs. The MCN is working to convene local leaders for shared learning and collaborative action towards that common purpose. MCN's mission is "ending youth poverty and violence one neighborhood at a time."

MCN is a growing collaboration between Emmanuel Gospel Center, Strategy Matters, Black Ministerial Alliance, Boston youth minister-at-large Rev. Mark Scott, and Vibrant Boston.

As a founding member of MCN, EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting team will continue to provide convening and infrastructure support.

Urban Youth Mentoring

he presence of a caring adult in the life of a youth is one of the key factors in influencing a child’s behavior. In addition to parenting, mentoring youth in an urban context provides a highly strategic social-spiritual opportunity to shape future generations and address broader societal issues, including youth violence. In this issue from 2008, EGC Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell summarizes his research on mentoring youth in an urban context. See also the concluding list of links and resources.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 41 — September/October 2008

Urban Youth Mentoring

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

The importance of mentoring youth has been identified in numerous studies which collectively establish the fact that the presence of a caring adult in the life of a youth is one of the key factors in influencing a child’s behavior. Therefore, in addition to parenting, mentoring youth in an urban context provides a highly strategic social-spiritual opportunity to shape future generations and address broader societal issues, including youth violence.

In this issue, reprinted from 2008, Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, summarizes his research findings regarding various practical aspects on mentoring youth in an urban context. Rudy’s research draws from both secular and faith-based sources regarding preparation, planning, recruiting, screening, training, matching, support, monitoring, closure, and evaluation of youth mentoring programs. Also included is a selected resource list that provides additional information and examples.

Urban Youth Mentoring

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, EGC

Mentoring, in combination with other prevention and intervention strategies, can make a significant contribution to reducing youth violence and delinquency. Research has shown that “the presence of a positive adult role model to supervise and guide a child’s behavior is a key protective factor against violence.”[1]

With careful planning; screening, training, and monitoring of volunteers; and sustained, long-term relationships by the mentors, the lives of at-risk youth can be changed. Christians can be involved by developing faith-based mentoring programs and by serving as mentors in existing programs. In either role they should make good use of the research and resources available in the general field of mentoring.

Preparation and Planning for a New Program

Starting a new mentoring program, even within an established organization, requires careful planning and design. It is important to have the support and active involvement of a board, either existing or newly created.

If you are working in an organization with an existing board, it is still valuable to have a separate advisory committee for the mentoring program.[2] These advisory groups can give guidance on how the initiative will fit in with other programs in the organization and community.

Another early planning step is to assess the needs of youth, survey the services of existing programs, and research the assets of the community. From this research, you can define what type of mentoring services to offer, what specific groups to focus on, and what outcomes may be most needed. One planning tool that can be helpful in defining outcomes is the Logic Model approach.[3]

Other aspects of planning are preparing training materials, developing policies, budgeting/fundraising, and planning record keeping. One must anticipate the need for adequate staffing in addition to recruiting the mentors.

It is important not to underestimate how much support, supervision, and counseling that staff may need to provide. Additional support and resources can be leveraged through collaborative partnerships with other community organizations, with schools, and with businesses.

Recruiting and Screening

When recruiting mentors, it is critical to find individuals who are willing and able to make long-term commitments and who will be dependable and consistent in meeting regularly with the mentee. Research has shown that when relationships break off after a short time, the result may be negative, not just neutral.[4]

During recruitment it is important to clearly present the expected time commitment and frequency of meetings with the mentees, as well as the overall expected duration of the mentoring relationship. Typically mentors are expected to meet with mentees at least four hours a month for one year (or one school year at school-based sites).[5] While the commitments need to be made clear when recruiting participants, the benefits also need to be highlighted.

Mentors should enjoy being with youth, be enthusiastic about life, and be good role models who can inspire youth. Good mentors also should be honest, caring, outgoing, resilient, and empathetic. Mentors will need to be open minded, non-judgmental, and good listeners, not seeking to always direct the agenda and activities.

Of course, mentors need to be carefully screened to be aware of past substance abuse problems, child abuse or molestation problems, criminal convictions, and mental problems. The essential parts of the screening process include a written application, an interview, several references (personal, employer), and criminal background checks (including sex offender and child abuse registries).[6] Some offenses would automatically disqualify a potential mentor, while other past events may raise red flags, but call for good judgment and general guidelines.

For programs not meeting at a fixed site, a home visit is recommended. In the screening process, it is valuable to learn about the motivations of potential mentors to make sure they are not just trying to fill their own unmet needs.

Potential mentors who are long-term members of a congregation and well known by the program staff can move through the approval process somewhat faster, although they still should be evaluated carefully and objectively using the essential and standard process.[7]

Training Mentors

Orientation of mentors can include a presentation of the programs goals, history, and policies. Benefits and hoped for outcomes can be described in ways that don’t generate unrealistic expectations. Orientation can also cover the general nature of the mentoring process.

It is valuable to have good printed literature on the program available at this time. Orientation is often used to recruit and introduce people to a mentoring program before they get involved.

Effective mentoring programs have good mentor training prior to establishing matches and have ongoing training or support. Training can cover communication skills, the stages of a mentoring relationship and how to relate to the mentee’s family. In the first stage of starting a match, the pair may need help in strategies for building trust and rapport, or suggestions for helpful activities.

Young people go through developmental stages which mentors need to be familiar with. Mentoring and other supportive services can be seen as valuable contributors to the overall youth development process. The training can also help mentors with cross-cultural and inter-generational understanding and communication.

Various types of problem situations and needs in the mentee’s life and in the mentoring relationship can be covered in preliminary and ongoing training. Mentors can also become knowledgeable of the social services which are available to help with potential problems.

Training can include ways to guide youth in setting goals, discovering their talents, and making decisions. Growing in these and other life skills, can build self-esteem, especially when appreciated and commended by mentors. It is important for mentors to understand current youth culture and the issues facing youth in the local community.

Some youth may experience emotional problems, and therefore, mentors may need some training in basic counseling skills and knowing when to make suggested referrals. During the training sessions, program policies and responsibilities should be reviewed, including regular reporting and child abuse reporting requirements. Programs with an academic focus may want to include a session on effective tutoring methods.

It is important to have a separate training session for the mentees as well. This will help them understand mentoring, what to expect of their mentor, and give practical suggestions on communication and activities.

Making Matches

The mentoring program needs to develop a weighted list of criteria for matching youth with mentors, criteria that correspond to the program’s priorities. While various criteria can be important, often the general quality of being an understanding listener turns out to make the most difference in developing a relationship.[8]

Basic criteria that can be critical include compatible time schedules and geographic proximity. If the mentoring involves social activities, it can be helpful to have common interests, hobbies, or recreational activities.

In more specialized programs, it may be necessary to match a youth who has certain career interests or academic needs with a mentor from that career field or academic skill set. Other criteria often considered in making matches are gender, language, race, cultural background, and life experiences.

It is also valuable to consider personality and temperament in making a match. Some complex personal qualities may be best sensed by intuition. Depending on the goals and values of the program, some criteria should be weighted more heavily than others.

The parents of the youth are generally given a voice in the process of choosing and approving a mentor. In any case written parental permission for general participation is necessary. Programs can also consider input and preferences from mentees and mentors.

Once the match is decided, the program should arrange a formal meeting for introduction at the organizational site. This meeting can include some icebreakers or activities, and can include a group of newly matched pairs.

Typically the best initial foundation of a good relationship is trust and friendship rather than achieving goals and tasks. “Research has found that mentoring relationships that focus on trying to change the young person too quickly are less appealing to youth and less effective. Relationships focused on developing trust and friendship are almost always more beneficial.”[9] Thus the initial activities and focus should seek to foster communication, trust, and rapport, rather than just accomplish tasks.

Ongoing Support, Training, and Monitoring

Ongoing support is one of the most important elements in a successful mentoring program. Mentors should be contacted within two weeks of the beginning of the relationship.[10] Program staff should then continue to maintain regular, personal communication weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly with the mentors.

In order to give adequate support it is recommended that a 20 to 1 ratio be maintained between mentors and support staff.[11] These personal contacts can help intervene to clear up misunderstandings, provide insights regarding cultural differences, and give encouragement.

In addition to good communication, the program can arrange regular meetings of mentors for discussion of problems, sharing ideas, and giving recognition and appreciation. Some of these mentor meetings can include additional training on issues facing a number of the mentors or youth.

Experienced mentors can help in training newer mentors. Online support groups could also be used to share ideas, ask questions, and discuss issues. Support staff may occasionally need to work out a new match, if the original match has been given plenty of time and effort, but is just not working out.

Closure and Evaluation

The mentoring program needs to have flexible procedures and support services to handle the closure of a match. A mentoring relationship may end naturally as a school year ends, or when one of the pair moves away. However, it may also end because of problems, incompatibility, disinterest, or violation of rules.

Because of the variety of reasons relationships end, the program needs to tailor its approaches to giving closure and support to the youth, mentor, and the family. It is just as important for the match to have a good closure as to have a good beginning.

Exit interviews are often used in closing a relationship. These may involve the mentor and mentee together or separately. Generally there should be a meeting with the family as well. These meetings can be a constructive learning experience, as reasons for the termination are clarified and discussed in a positive way. The youth should be encouraged to share feelings about what went well and what could have been improved.

It is helpful for the mentor and mentee to share what they enjoyed most in the relationship. When the match ends because the mentor is no longer able to continue, it is especially important to reassure the youth that the ending is not due to anything he or she did. Where appropriate, the staff can discuss possible future matches in the current program, or elsewhere (if one participant is moving).

Exit interviews can also play a valuable role in evaluation. Program evaluation can be done by your own staff, using or adapting the many survey tools available,[12] or by an outside evaluator (possibly drawing on an university department or a grad student intern).

One can evaluate the effectiveness of various processes of implementing the overall program, but it is even more important to evaluate the goals and outcomes you have established for and with the youth. These outcomes can guide the choice of measures and data needed for evaluation.

Typically, a baseline of information should be gathered when youth begin, and then progress can be measured after the matches have been going at least six months to a year.[13] If possible, try to also get information on a comparable group which was not mentored. Data sources may include the youth, mentors, family, school records, teachers, and police.

Don’t assume your program was the only cause of any improvement. However, as you follow the guidelines for effective practices and work collaboratively with the youths’ families, other organizations serving youth, and the schools, you can expect to see a positive difference in the lives of young people.

Footnotes

1 Timothy N. Thornton., Carole A. Craf, Linda L. Dahlberg, Barbara S. Lynch, and Katie Baer, Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action (New York: Novinka Books, 2006), 150.

2 Michael Garringer and Pattti McRae, editors. Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring, rev. ed. (Washington, D. C.: Hamilton Fish Institute and the National Mentoring Center, 2007), 8.

3 W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Logic Model Development Guide, http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub3669.pdf (14 Nov. 2008).

4 D.L. DuBois, B.E. Holloway, J.C. Valentine, and H. Cooper. “Effectiveness of Mentoring Programs for Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30, no. 2 (April 2002):157-197.

5 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice (Alexandria, Vir.: National Mentoring Partnership, 2005), 10.

6 Garringer and McRae, 29.

7 Shawn Bauldry, and Tracey A. Hartmann, The Promise and Challenge of Mentoring High-Risk Youth: Findings from the National Faith-Based Initiative (Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, n.d.), 14-15.

8 Maureen A. Buckley and Sandra Hundley Zimmermann, Mentoring Children and Adolescents: A Guide to the Issues (Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003), 43.

9 Bauldry, and Hartmann, The Promise and Challenge of Mentoring High-Risk Youth, 20.

10 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice, 105.

11 Timothy N. Thornton., et al, Youth Violence Prevention, 171.

12 National Mentoring Partnership, How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice, 171-172. 13 Garringer and McRae, 58.

Resources and Links

Buckley, Maureen A., and Sandra Hundley Zimmerman. Mentoring Children and Adolescents: A Guide to the Issues. Contemporary Youth Issues. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

This is a practical and comprehensive handbook which includes sample mentor and mentee applications, a full sample grant proposal/program design, and detailed quality standards for effective programs. The authors provide an annotated list of print and non-print resources, as well as detailed information on state and national organizations and key people. Several chapters give an overview of practical aspects of formal mentoring programs and summarize facts and research studies.

Dortch, Thomas W., Jr., and The 100 Black Men of America, Inc. The Miracles of Mentoring: How to Encourage and Lead Future Generations. New York: Broadway Books, 2001.

Drury, K.W., editor. Successful Youth Mentoring: Twenty-four Practical Sessions to Impact Kid’s Lives. Loveland, Calif.: Group Publishing, 1998.

DuBois, D.L., B.E. Holloway, J.C. Valentine, and H. Cooper. “Effectiveness of Mentoring Programs for Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Journal of Community Psychology 30, no. 2 (April 2002):157-197.

The authors reviewed 55 research evaluations of mentoring programs. They found that disadvantaged and at-risk youth benefit most from mentoring. Significant positive effects depend on the use of best practices and developing strong relationships. Poorly implemented programs can have a negative effect on youth; therefore, it is important for programs to use effective methods of planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Dubois, David L., and Michael J. Karcher, editors. Handbook of Youth Mentoring. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2005.

This is one of the most comprehensive recent works on the theory, research, and practice of mentoring youth. Under the section on theory and frameworks, Jean Rhodes presents a theoretical model of mentoring where relationships of mutuality, trust, and empathy promote social-emotional, cognitive, and identity development. For formal mentoring programs, the handbook gives useful material on developing and evaluating a program, and on recruiting and sustaining volunteers. In addition to covering various types of mentoring (natural, cross-age, intergenerational, e- mentoring), the book also considers mentoring in various contexts (schools, work, after-school, faith-based organizations, and international settings), and with specific groups (at-risk students, juvenile offenders, gifted youth, pregnant/parenting adolescents, abused youth, and youth with disabilities).

Freedman, Marc. The Kindness of Strangers: Adult Mentors, Urban Youth, and the New Voluntarism. Revised ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Over three hundred interviews were conducted to produce this important work on urban youth mentoring. It distills guidelines and principles for effective mentoring programs and gives overviews of some mentoring efforts around the country. While realistically looking at pitfalls and problems, the book offers a hopeful perspective on mentoring as one important part of the solution to youth violence and other problems.

Hall, Horace R. Mentoring Young Men of Color: Meeting the Needs of African American and Latino Students. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2006.

Hall advocates mentoring and other strategies to channel care and concern for young men to enable them to reach their potential despite the challenges they face.

National Mentoring Center—http://www.nwrel.org/mentoring/index.php

The National Mentoring Center (NMC) has been serving youth mentoring programs of all types since 1999. Originally created by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), the National Mentoring Center offers training, resources, and online information services to the entire mentoring field. The NMC now houses the LEARNS project, which provides training and technical assistance to mentoring projects supported by the Corporation for National and Community Service. The NMC also works in partnership with EMT Associates to manage the Mentoring Resource Center.

Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring is the Center’s cornerstone resource for developing all types of youth mentoring programs across a variety of settings. It is a useful resource for start-up efforts and established programs alike. This 114 page guidebook is available free from the website, and covers all aspects of developing a mentoring program, with included charts and sample forms.

National Mentoring Partnership/MENTOR—www.mentoring.org

An advocate and resource for the expansion of quality mentoring initiatives nationwide. This networking organization builds and supports state mentoring partnerships, sponsors the National Mentoring Institute, develops resources like the Elements of Effective Practice, and encourages research and support for mentoring. The website makes available many great resources including:

Elements of Effective Practice, guidelines and detailed action steps developed by leading national authorities on mentoring. They were recently revised, taking into account solid research to help mentoring programs plan effective organizations that will nurture quality, enduring mentoring relationships. Available free at: http://www.mentoring.org/downloads/mentoring_411.pdf.

How to Build a Successful Mentoring Program Using the Elements of Effective Practice. While the previous resource provides a detailed outline, this handbook discusses in detail the considerations and methods of carrying out the steps needed to develop a quality mentoring program. It covers design and planning, managing, implementing, and evaluating the program. Many specific forms, handouts, lists, and guidelines are included, esp. on the CD. This 188 page “toolkit” handbook can be downloaded free at www.mentoring.org/eeptoolkit or purchased in print and CD format.

The Mass Mentoring Partnership (Mass Mentoring)—www.massmentors.org is the state partner of the National Mentoring partnership.

Rhodes, Jean. E. Stand By Me: The Risks and Rewards of Mentoring Today’s Youth. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Rhodes draws on her own research and also an analysis of research by Public Private Ventures to inform her well-written study. Well trained mentors who develop good, long-term mentoring relationships can make a difference in the lives of at-risk youth by improving their social skills, develop their thinking and academic skills through dialog, and by serving as advocates and role models. She also provides cautions about the risks of ineffective and damaging mentoring relationships.

Sipe, Cynthia L. Mentoring: A Synthesis of P/PV’s Research, 1988-1995. Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, 1996. Available as a free download at: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org.

In addition to reviewing the major findings of Public/Private Ventures’ mentoring research, this synthesis summarizes ten different research reports of the period.

Thornton, T. N., C.A. Craf, L. L. Dahlberg, B.S. Lynch, and K. Baer. Youth Violence Prevention: A Sourcebook for Community Action. New York: Novinka Books, 2006. See pages 149-192.

One of the four major strategies to prevent youth violence covered in this sourcebook is mentoring. The material here is especially helpful because it reviews and summarizes a wide range of research and resources. It surveys community-based and site-based mentoring with reviews of research on Big Brothers/Big Sisters and the Norwalk Mentor Program. It deals with staff and mentor recruiting and training principles and resources, goal setting, activities, and evaluation. The guide to books, research, training materials, and organizations offers many useful resources.

Find more youth mentoring resources at Culture and Youth Studies: http://cultureandyouth.org/mentoring/

Take Action

RESEARCHING YOUR CITY FOR MINISTRY IMPACT

Resource List used by Nika Elugardo for Movement Day 2016.

Resources for Research

PRESENTER’S WEB CONNECTIONS

· Berlin – Gemeinsam für Berlin (Together for Berlin) http://www.gfberlin.de/startseite

· Boston – Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) – http://www.egc.org/

· South Africa –

o Jewels of Hope http://jewelsofhope.org/

o Johannesburg Housing Company – http://www.jhc.co.za/

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH FROM EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER (EGC)

Note: EGC is engaged in a website makeover. We are working to migrate files from our old site to the new one as quickly as we can. Some of these resources may not be available right away.

· New England’s Book of Acts. Stories of how God is growing the churches among many people groups and ethnic groups in Greater Boston. https://www.egc.org/blog-2/new-englands-book-of-acts.

· What is the Quiet Revival? an overview:

What is the Quiet Revival? Fifty years ago, a church planting movement quietly took root in Boston. Since then, the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled.

http://www.egc.org/blog/2016/10/13/understanding-bostons-quiet-revival

· Youth Violence System Project (YVSP) – http://www.gettingtotheroots.org/

o YVSP Neighborhood Studies — http://www.gettingtotheroots.org/community

o YVSP overview — Khary Bridgewater, et al, “A Community-Based Systems Learning Approach to Understanding Youth Violence in Boston,” Progress in Community Health Partnership: Research, Education, and Action) http://www.gettingtotheroots.org/aes/sites/default/files/yvsp_sprev_article1.pdf

· Boston Church Directory — print editions 1989 to 2001; online condensed edition at http://egcboston.force.com/bcd

Other EGC studies (some available in print, all will be available online in the near future at egc.org)

· The Unsolved Leadership Challenge (2014; church planting and women in leadership)

· Christianity in Boston (1993; discovery of Quiet Revival)

· Educating Urban Christians in the 21st Century (1998; needs assessment study)

· Youth Ministry in Boston (1995; needs assessment survey)

· Studying Urban Communities (1994, and updates; questionnaire and study guide)

SOME EXCELLENT CITY RESEARCH TOOLS & ORGANIZATIONS

Center for the Study of Global Christianity: (Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary) does research to maintain the World Christian Database, which has data on over 5,000 cities. It also is the repository for research collected by the World Evangelisation Research Center in Nairobi, Kenya. Other resources include the World Christian Encyclopedia and the Atlas of Global Christianity. Director Todd Johnson. http://www.gordonconwell.edu/ockenga/research/index.cfm

Community Tool Box: a major, free online set of resources for anyone seeking to improve communities or foster social change. Among the 46 areas covered in English, Spanish and Arabic are several related to research: “Assessing Community Needs and Resources” (Ch. 3), Evaluation Research (Chs. 36-39), and “Analyzing Community Problems and Solutions” (Ch. 17). Associated with the Univ. of Kansas. http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents

Global Research, International Mission Board (IMB) & Global Research Information Center http://public.imb.org/globalresearch/Pages/default.aspx

Lausanne International Researchers Network https://www.facebook.com/LausanneInternationalResearchersNetwork/

Minneapolis - St. Paul City View Reports: by John A. Mayer; religious demographics of the twin cities. http://cityvisiontc.org/?page_id=535

Movement of African National Initiatives (MANI): Continental Coordinator, Reuben Ezemadu; research focused on discovering unreached groups. http://maniafrica.com/research/

OC Research (Department of One Challenge International) http://www.ocresearch.info

Operation World, Patrick Johnstone; prayer oriented research on all countries (7th ed.) http://www.operationworld.org/

BOOKS & ARTICLES ON URBAN CHURCH & COMMUNITY RESEARCH

Conn, Harvie M., and Manuel Ortiz. Urban Ministry: The Kingdom, The City, and the People of God. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2001. See also Section 1 in Planting and Growing Urban Churches: From Dream to Reality, edited by Harvie M. Conn. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1997.

Conn, Harvie M. Urban Church Research: Methods and Models: Collected Readings. Philadelphia: Westminster Theological Seminary, 1985.

Dudley, Carl S. Community Ministry: New Challenges, Proven Steps to Faith Based Initiatives. Herndon, Virginia: Alban Institute, 2002. See especially part I.

Eisland, Nancy L. and R. Stephen Warner. “Ecology: Seeing the Congregation in Context.” In Studying Congregations: A New Handbook, edited by Nancy T. Ammerman, Jackson W. Carroll, Carl S. Dudley, and William McKinney. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1998.

Hadaway, C. Kirk. “Learning from Urban Church Research.” Urban Mission, January 1985, 33-44.

Lingenfelter, Judith. “Getting to Know Your New City.” In Discipling the City: A Comprehensive Approach to Urban Mission, 2nd edition, edited by Roger S. Greenway. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1992.

Monsma, Timothy M. “Research: Matching Goals and Methods to Advance the Gospel.” In Discipling the City: A Comprehensive Approach to Urban Mission, 2nd edition, edited by Roger S. Greenway. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1992.

Nussbaum, Stan. Breakthrough: Prayerful, Productive Field Research in Your Place of Ministry. 2nd edition. Colorado Springs, Colorado: GMI Research Services, 2011. Website for GMI Research - http://www.gmi.org/about-us/

Sider, Ronald J., Philip N. Olson, and Heidi Rolland Unruh. Churches That Make a Difference: Reaching Your Community with Good News and Good Works. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 2002. See chapter 12.

Taylor, Dick. “Discovering Your Neighborhood’s Needs.” Sojourners, June 1979, 22-24.

BOOKS & ARTICLES ON GENERAL RESEARCH METHODS

Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13, no. 1 (January 2012): Article 30. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1801/3334 Special issue on participatory qualitative research and action research.

Beukes, Anni. “Know Your City: Community: Profiling of Informal Settlements.” IIED Briefing: Policy and Planning, June 2014, http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/17244IIED.pdf. Importance and methods of gathering data on informal urban communities to work for community improvements.

Chevalier, Jacques, and Daniel J. Buckles. Handbook for Participatory Action Research, Planning and Evaluation. Ottawa, Canada: SAS2 Dialogue, 2013. Accessed 7 Oct. 2016. http://www.sas2.net/sites/default/files/sites/all/files/manager/Toolkit_En_March7_2013-S.pdf

Creswell, John W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3nd edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2013. A practical book covering narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study approaches.

Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Social Research Projects. 5th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill / Open University Press, 2014. Contains helpful checklists, summaries, and text boxes highlighting the essentials of basic research methods.

Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2011. A standard text on the subject containing contributions from many leading international scholars.

DeWalt, Kathleen M., and Billie R. DeWalt. Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. 2nd edition. Lanham, Maryland: AltaMira Press, 2010.

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. Very specific and well-illustrated guidance on collecting and writing up ethnographic field observations.

Krueger, Richard R., and Mary Anne Casey. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2015.

Leedy, Paul D., and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod. Practical Research: Planning and Design. 11th edition. Upper Saddle River, N. J.: Pearson, 2015. This book has gone through many editions and is useful in many subject areas of research.

Mack, Natasha, Cynthia Woodsong, Kathleen M. MacQueen, Greg Guest, and Emily Namey. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: Family Health International, 2005. Available free online at: https://www.fhi360.org/resource/qualitative-research-methods-data-collectors-field-guide. This resource is designed for use in international settings and developing countries.

Morgan, David L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1996. See also Morgan and R.A. Krueger, The Focus Group Kit (6 volumes also published by Sage).

Saldana, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2016. Coding is an important process in analyzing qualitative research data, and this book gives detailed examples and a great variety of methods used in coding.

Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie L. DeVault. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. 4th edition. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2016. Contains extensive material on participant observation, in-depth interviewing, and working with qualitative data.

Weiss, Robert S. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: The Free Press, 1994. Includes examples and excerpts from interview transcripts with comments.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5th edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2014. A standard work on case study research.

Keeping Work in its Place

Happy Fall from the EGC Woven crew! I want to share a tidbit of wisdom from one of the table groups at the May Woven Consultation to help us stay balanced this fall...

Keeping Work in its Place

By WOVEN SEPTEMBER 30TH, 2016

Happy Fall from the EGC Woven crew! I want to share a tidbit of wisdom from one of the table groups at the May Woven Consultation to help us stay balanced this fall:

Don’t let your work be an idol—

Seek healing for the holes in ourselves.

Be whole in God

Be rooted in Christ.

As we know, letting something be an idol means looking to something other than God to make our lives worthwhile—to make life worth living or give us personal worth. Idols cause anxiety and imbalance because they can never be as secure or enduring as our relationship with God.

Over the years I’ve contended with the idol of achievement. I’ve mis-measured my life‘s worth based on how much I was accomplishing. When I give in to that idol, I overtax my body, cut corners on my spiritual life, and rationalize emotional chaos as the cost of doing business.

Others may be tempted to make idols of their work in other ways—maybe they lean too hard on their work to give them respect, purpose, or power to provide, not ultimately trusting God for those needs.

How can we avoid making work an idol? I find these prayerful reminders helpful:

1. God, my life’s worth (or dignity, or provision) comes from You. My work is just what I do for now.

2. Lord, help me make today be less about working for You, and more about walking with You.

3. Holy Spirit, help me to draw work boundaries in places that are pleasing to You.

I’ll leave you with the wisdom of one Woven participant—“We see success as fulfilling our mission in life, but God sees our obedience as success.”

Want to write (or video?) a personal reflection for the Woven community on what helps you stay balanced? Let us know! Email Jess at jmason [at] egc.org.

Jess Mason is a licensed minister, spiritual director, and research associate in ARC@EGC. Her passion is to see God’s goodness revealed to and through Christian leaders and pillars in the Boston area.

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge

![Inner Life Of A Leader [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1503082360379-C5ZBYKU7T85I40JH5WMS/pexels-inner-life-airballoon.jpg)

![Intercultural Leadership [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1503082407845-5YCT4DLA93VIGHBSAN1R/pexels-intercultural.jpeg)

![Hidden Treasures: Celebrating Refugee Stories [photojournal]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1512579164575-AKNVCYX4Q5DW8IN2CNYP/P1070998.jpg)

![Modern Classics on Leadership [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1503082448262-DU5B4OH1ZP625DKJRZHH/pexels-modernclassics.jpeg)

![Women In Christian Leadership [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1503082489913-T7DT6XUHEQE5DLCQ91UP/pexels-womanleader.jpeg)

![Hard Steps Toward the Light: Meet Bonnie Gatchell [Interview]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1524836375191-XIDDMMVWWA04WYY5D1L6/3+a.+Route+One-+Bonnie+Tedx.png)

![2016 WOVEN CONSULTATION [Photojournal]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1476666331174-5QUVROVZFAWEBDXCU15P/Screen+Shot+2016-10-16+at+6.05.15+PM.png)

![Pastoral Leadership [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1505489535138-EG2UJ0K00MI0BXPQTNZ5/pexels-pastor.jpg)

![Leadership Strategies & Models [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1505489580322-W3YPVU5W1AKQXXNOLFUM/pexels-strategyleadership.jpeg)

![Homelessness & Collaboration: Starlight Ministry [VIDEO]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1523389821793-ZWG4LOT4ZTF83A6JKKS1/Cynthia+Starlight+Video+HiDef.png)

![Street Involvement As A System [infographic]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1506610840159-GYRRV17PMQVSKQWTKDX8/street+involved.jpeg)

What do Christian women leaders report hearing or believing that they "shouldn't" want or need if they were a good leader? What kinds of life-giving connections to Christian women leaders want more of?