BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

EGC’s (Inaugural) Shalom-Seekers Book List

Which books help you pursue the shalom of the city and the glory of God? Here are some titles that have contributed meaningfully to our shalom-seeking in Boston.

EGC’s (Inaugural) Shalom-Seekers Book List

Liza Cagua-McAllister for EGC staff

The Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) exists to catalyze kingdom-centered, systemic change for the shalom of the city and the glory of God. If you are also on this amazing mission, our staff recently put together a list of books that have influenced and helped us along this challenging journey!

We asked our team: What books from diverse authors have you read that have contributed meaningfully to your shalom-seeking in the urban context? Why were these books significant to you?

Submissions ranged from systems thinking primers to books on racial healing, from urban ministry classics to challenging new works less than a year old. From the 28 books mentioned by our team, we selected about a dozen to display in our EGC breakroom. Here are a few of those noteworthy titles, with staff comments.

“I find this book important for shalom-seeking in the urban context because... ”

A Multitude of All Peoples

A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity's Global Identity by Vince L. Bantu (2020)

In order to know where we are headed, we need to know where we’ve been. Dr. Bantu — a former EGC staff member — brilliantly challenges Western mental models and makes the case for how the Church’s very foundation is multicultural.

Buried Seeds

Buried Seeds: Learning from the Vibrant Resilience of Marginalized Christian Communities by Alexia Salvatierra and Brandon Wrencher (2022)

Rev. Dr. Salvatierra and Rev. Wrencher glean powerful learnings from faith communities facing brutal challenges and evidencing tremendous power and imagination! From these historic movements, they offer present-day applications to different audiences, which is very helpful given urban shalom-seekers’ diverse experiences and social locations.

The Color of Compromise

The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism by Jemar Tisby (2020)

Dr. Tisby offers an eye-opening and thoughtful account of how the Church has been complicit in creating and maintaining the unjust structures of systemic racism in America. This is an important book for understanding one of the key issues of our times.

Ecosystems of Jubilee

Ecosystems of Jubilee: Economic Ethics for the Neighborhood by Adam Gustine and José Humphreys III (2023)

The authors richly engage Scripture to address the relationship between justice and economics, which is so central to making things right in our world. We can’t really live out the gospel without having it reshape our economic ethics, and this is a great beginning!

Seek the Peace of the City

Seek the Peace of the City: Reflections on Urban Ministry by Dr. Eldin Villafañe (1995)

Dr. Villafañe applies the “Jeremiah paradigm” for ministry in the city, laying the biblical and theological groundwork for engaging issues such as violence and reconciliation in the city with the wisdom and truth of God’s word.

Thinking in Systems

Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella H. Meadows (2008)

We work in a complex web of interrelated living systems. Understanding systems is fundamental to our work, and this is the classic primer on what systems are and why they matter. It’s a great starting point or great refresher for your systems journey.

Other titles you can find in the EGC breakroom:

Beholding Beauty: Worshiping God through the Arts by Jason McConnell (2022)

Beyond Welcome: Centering Immigrants in our Christian Approach to Immigration by Karen González (2022)

First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament trans. by Terry M. Wildman with consultant editor First Nations Version Translation Council (2021)

Healing Racial Trauma: The Road to Resilience Paperback by Sheila Wise Rowe (2020)

I Bring the Voices of My People: A Womanist Vision for Racial Reconciliation by Chanequa Walker-Barnes (2019)

The Alternative: Most of What You Believe About Poverty is Wrong by Mauricio Miller (2017)

The Anatomy of Peace: Resolving the Heart of Conflict by The Arbinger Institute (2006)

Come by EGC to borrow one of these copies, check them out at your local library, or purchase them at your local, independent bookstore through bookshop.org!

These books help us pursue the shalom of the city for the glory of God. How about you?

Do you know where you’re standing?

Why EGC’s new “Fact Friday” series explores the church’s history and legacy in Boston one short video at a time.

Updated Feb. 21, 2024

Do you know where you’re standing?

Why EGC’s new “Fact Friday” series explores the church’s history and legacy in Boston one short video at a time.

by Hanno van der Bijl, Managing Editor, Applied Research & Consulting

Did you know that the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill was co-founded by Cato Gardner, a formerly enslaved man born in Africa?

Or that Twelfth Baptist Church was the spiritual home of Wilhelmina Crosson, a pioneering Black school teacher in Boston, who also was instrumental in launching the precursor to Black History Month?

How about this gem: Boston’s oldest church congregation is not downtown — it’s in Dorchester. On June 6, 1630, the First Parish Church in Dorchester was the first congregation to meet in what is present-day Boston. The First Church of Boston did not organize until about two months later.

These are just some insights from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s new “Fact Friday” video series on Instagram.

“The city’s churches have a rich history,” said Caleb McCoy, marketing manager at EGC. “I think those legacies impact how we view the church today, so it’s important to share that information with as many as possible.”

The Fact Friday team includes Jaronzie Harris, program manager for the Boston Black Church Vitality Project, and Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher at EGC. Since February, this dynamic duo has been creating videos exploring the church’s long history in Boston, leaving EGC’s Instagram followers hungry for more.

“People who live in Boston may walk by church buildings but they may not know, one, what has gone on there in the past and, two, what’s going on here in the present,” Mitchell said.

Bridging that gap between the past and present is one of the project’s key motivators.

“It’s been fun for me to share but also to learn,” Harris said. “Doing this project is engaging me in research. I have to go and find out about these things, which I enjoy doing.”

Harris said learning about St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church’s rich history, for example, led her to discover some surprises about the church’s ministry today as she listened to a recent sermon.

“It was interesting to hear this minister preaching Black theology from a different tradition about a festival I didn’t know about,” Harris said. “I haven’t heard that type of militant preaching in Boston before.”

Caleb McCoy (right) films a recent Fact Friday video with Rudy Mitchell (left) and Jaronzie Harris (center).

The city’s Black churches have a rich legacy of gospel ministry and social action.

“Almost every time you look at one of the Black churches in the 1800s, you see they were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement and advocating for the rights of enslaved peoples,” Mitchell said. “A lot of rich history inspired continued activism in more recent times.”

The team believes the Black church’s spiritual legacy continues to buoy the community as it faces its own headwinds today.

“We are in a time that’s very racially charged right now,” McCoy said, “but it’s important to know that Black Christianity and the Black church has a legacy that’s gone before us and has a rich history in the fight for equality and justice in our own city.”

The team also enjoys parsing out curiosities such as why a church on Warren Street in Roxbury is called “The Historic Charles Street AME Church.”

In addition to digging around the past, the project has a forward-looking orientation. Boston, for example, was home to the first YMCA in the United States. What would such an innovative approach to ministry look like today?

“The Bible often tells us to remember how God was at work in the past, and we certainly can learn from history,” Mitchell said. “Even though the form and methods may change, we can be inspired to be used by God in our own time for similar purposes.”

For decades, EGC has been channeling its research and learning into specific programming and events. The Boston Church Directory, for example, demonstrates how its use of applied research is a dynamic process, bringing people in along the way.

But learning is ongoing, and it’s important to share that process, Harris said.

“I’m learning these things for Fact Friday, sure, but I’m also learning these things to better support my churches, to better understand the Boston landscape,” she said.

EGC also tries to provide a larger perspective on Christianity in Boston not just across different denominations and cultural groups but also over time. At times that research has uncovered illuminating insights.

“Historically, we saw that, between 1970 and 2010, more new churches started in Boston than in any other comparable period in Boston’s history,” Mitchell said.

Many of those churches have important stories to tell, known only by a few. Through various research projects, EGC tries to get those stories out in the open.

“We have all this historical information,” Harris said. “So how can we tell a story that is digestible for a broader audience?”

Here are some of the churches, institutions, sites, and individuals the team has covered so far:

TAKE ACTION

Follow EGC on Instagram @egcboston and watch for new reels and videos on Fridays.

What would you like to know about the history of the church in Boston? Let us know by filling out the feedback form below.

Additional Resources

Curious to learn more about the story of the church in Boston? Give these resources below a try.

Daman, Steve. “Understanding Boston’s Quiet Revival.” Emmanuel Research Review. December 2013/January 2014. Accessed January 22, 2015.

Hartley, Benjamin L. Evangelicals at a Crossroads: Revivalism and Social Reform in Boston, 1860-1910. Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2011.

Hayden, Robert C. Faith, Culture and Leadership: A History of the Black Church in Boston. Boston: Boston Branch NAACP, 1983.

Horton, James Oliver, and Lois E. Horton. Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, rev. ed. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 2000. See chapter 4: “Community and the Church.”

Johnson, Marilynn S. "The Quiet Revival: New Immigrants and the Transformation of Christianity in Greater Boston." Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation V 24, No. 2 (Summer 2014): 231-248.

Mitchell, Rudy. The History of Revivalism in Boston. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007.

Mitchell, Rudy, Brian Corcoran, and Steve Daman, editors. New England’s Book of Acts. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007. The New England Book of Acts has studies of the recent history of ethnic and immigrant groups and their churches and a summary of the history of the African-American church in Boston.

History of Revivalism in Boston

Journey with EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell through Boston’s key evangelistic revivals from the First Great Awakening in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign of 1950. History comes alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through gifted evangelists, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

History of Revivalism in Boston

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 24 — January/February 2007

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Read the full version online here.

Executive Summary

“Revivalism,” according to the Dictionary of Christianity in America, “is the movement that promotes periodic spiritual intensity in church life, during which the unconverted come to Christ and the converted are shaken out of their spiritual lethargy.” David W. Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland and a distinguished visiting professor of history at Baylor University, describes revivalism as a strand of evangelicalism, a form of activism (which he identifies as one of evangelicalism’s four key characteristics), where a movement produces conversions “not in ones and twos but en masse.”

Dwight L. Moody revival meeting in Boston

In this 2007 study, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell traces Boston’s key evangelistic revival movements from the First Great Awakening in Boston in 1740–1741 through the Billy Graham campaign in Boston, starting on New Year’s Eve in 1949. With 23,000 attending services on the Boston Common in 1740 to hear Whitefield (without the benefit of electronic amplification) to an estimated 75,000 gathered at the same spot in 1950 to hear the same Gospel preached by Rev. Billy Graham, the story of revivalism in Boston gives color and texture to the waves of revival.

Rudy introduces us to a few of the key players, remarkable crowds, recorded outcomes, while weaving in familiar faces and places, from Charles Finney, Dwight L. Moody and Billy Sunday to Harvard Yard, Park Street Church and the Boston Garden. We sense history coming alive as we read how God moved in remarkable ways through his gifted evangelists and preachers, and we gain a deeper appreciation for Boston’s vibrant Christian history.

“History of Revivalism in Boston” was first printed in the January/February 2007 issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, Issue 24. It was subsequently published in New England’s Book of Acts, a collection of reports on how God is growing the churches among many people groups and ethnic groups in Greater Boston and beyond.

Table of Contents (with key themes and names added)

First Great Awakening in Boston

Learn More

Read the full version of “History of Revivalism in Boston”

Contact Rudy Mitchell with questions, or to request a printed copy.

Examples of Collaboration in the Greater Boston Church Community

There has been a rich history of ministry collaboration in the Greater Boston Christian community. This document gives a brief description of some of the significant ministry initiatives in urban Boston that involved a broad coalition of ministry partners, and/or involved significant partnering across sectors. Much more could be said about each of the ones listed, and many more initiatives, projects and ministries could be added to this list.

Compiled by the Emmanuel Gospel Center for Greater Things for Greater Boston Retreat October 8 – 10, 2017

There has been a rich history of ministry collaboration in the Greater Boston Christian community. This document gives a brief description of some of the significant ministry initiatives in urban Boston that involved a broad coalition of ministry partners, and/or involved significant partnering across sectors. Much more could be said about each of the ones listed, and many more initiatives, projects and ministries could be added to this list. Please send additions or other feedback to Jeff Bass (jbass@egc.org).

The 1857-1858 Prayer Revival spread to Boston when the Boston "Businessmen's Noon Prayer Meeting" started on March 8, 1858, at Old South Church (downtown). There was considerable doubt about whether it would succeed, but so many turned out that a great number could not get in. The daily prayer meetings were expanded to a number of other churches in Boston and other area cities. Wherever a prayer meeting was opened, the church would be full, even if it was as large as Park Street Church. While the revival was noted for drawing together businessmen, it also involved large numbers of women. For example, the prayer meetings of women at Park Street Church were full to overflowing with women standing everywhere they could to hear.

When Dwight L. Moody came to Boston in 1877, he led a cooperative evangelism effort among many churches. This three-month effort drew up to 7,000 people at a time to the South End auditorium for three services a day, five days a week. Moody encouraged a well-organized, interdenominational effort by 90 churches to do house-to-house religious visitation, especially among people who were poor. Two thousand people were spending a large part of their time in visitation, covering 65,000 of Boston’s 70,000 families. The home visitations served the practical needs of mothers and children as well as their spiritual needs. The Moody outreach also related to workers in their workplaces. Meetings were established for men in the dry-goods business, for men in the furniture trade, for men in the market, for men in the fish trade, for newspaper men, for all classes in the city.[1]

[1] These first two are from History of Revivalism in Boston by Rudy Mitchell; 50 pages of fascinating and inspiring reading. Use hyperlink or search at egc.org/blog.

One of the most important organizations in Boston for the healthy growth of the church has been Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston Campus, commonly known as CUME (the Center for Urban Ministerial Education). A short version of its interesting history is that it came about because of the joint hard work of leaders in the city (particularly Eldin Villafañe and Doug Hall) and leaders at the Seminary (particularly Trustee Michael Haynes, pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury). CUME officially opened with 30 students in September 1976 at Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury. CUME currently serves more than 500 students representing 39 denominations, 21 distinct nationalities, and 170 churches in Greater Boston. Classes are taught in English, Spanish, French Creole and Portuguese, with occasional classes in American Sign Language. (from GCTS website).

The Boston TenPoint Coalition was formed in 1992 when a diverse group of urban pastors was galvanized into action by violence erupting at a funeral for a murdered teen at Morning Star Baptist Church. Reaching beyond their differences, these clergy talked with youth, listened to them and learned about the social, economic, moral and ethical dilemmas trapping them and thousands of other high-risk youth in a cycle of violence and self-destructive behavior. In the process of listening and learning, the Ten-Point Plan was developed and the Boston TenPoint Coalition was born.

The “Boston Miracle” was a period in the late 1990s when Boston saw an unprecedented decline in youth violence, including a period of more than two years where there were zero teenage homicide victims in the city. Much has been written about The Boston Miracle (and a movie starring Matt Damon is in the works), but there are competing narratives about what caused the violence to decline. Certainly the work of Boston police, the Boston TenPoint Coalition, Operation Ceasefire, and supporting prayer all played major roles.

In response to the first Bush administration’s faith-based initiative in the early 1990s, a group of funders (led by the Barr and Hyams foundations) brought together leaders from the Black Ministerial Alliance (BMA), Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC), Boston TenPoint Coalition, and the United Way to respond to a Federal request for proposals. Out of this conversation, the Boston Capacity Tank was formed, and we were able to successfully secure a Federal grant ($2 million per year for three years, then funding from federal, state, local, private sources afterwards). The Tank was led with input from the founding partners, and built the capacity of more than 350 youth serving organizations over 10 years.

Victory Generation Out-of-School Time Program (VG) was created by the Black Ministerial Alliance in 1992 in response to the educational disparities documented between youth of color and their suburban counterparts. The BMA partnered with 10 churches to provide academic enrichment to students in the Boston Public Schools in order to improve their grades and test scores. Ninety-four percent (94%) of students consistently participating in VG were found to increase one full letter grade in achievement and, for those not at grade level, achieve grade level. Most remarkable is that although this is a church-centered program, upwards of 80% of the students attending VG are not members of any church.

In the 1990s, Vision New England hosted three-day prayer summits for male pastors that was attended by as many as 90 leaders. The goal was to focus purely on seeking God through prayer, worship and reading Scriptures with no speakers, only facilitators keeping things on track. They were not only well attended but powerful times that were blessed by the Holy Spirit. In 2000, leaders in Boston met to discuss holding a similar prayer summit that also would include female leaders in the Boston area. Thus began the Greater Boston Prayer Summit, which ran two-day prayer retreats for up to 75 pastors and ministry leaders in the spring, with a smaller one-day prayer gathering in the fall. The Summits were effective in connecting leaders around Greater Boston, and promoting unity in the church across various church streams. Energy for the Summit faded in recent years, and the planning team disbanded in 2016.

In the mid-1990s, there was a group of pastors and business leaders who met several times to talk about issues in the city and potential partnering. The business leaders challenged the city leaders to agree on an issue to address. “If the city leaders agree, resources will flow!” Partly in response to this challenge, EGC worked with a broad coalition of churches and youth leaders to start the Youth Ministry Development Project (YMDP). The goal, set by the coalition, was to see the Boston churches grow from only one full-time church-based youth worker to twenty over ten years, and to provide much better support for church-based youth work. Funding was provided primarily by secular foundations, and the YMDP project was well-funded and met its 10-year goals.

Boston Capacity Tank’s Oversight Committee (including funders and faith leaders) challenged itself to look at the systemic issues of youth violence in Boston. The Committee asked EGC to take the lead in forming the Youth Violence Systems Project (YVSP) that partnered with Barr, youth leaders in several key Boston neighborhoods, local organizations such as the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), the Boston TenPoint Coalition (to interview gang members), and a nationally known Systems Dynamics expert (Steve Peterson). The work influenced many leaders to take a more systemic view of their activities, and the project approach was published in a peer review journal.

In 1997, United Way of Massachusetts Bay (UWMB) collaborated with local faith leaders to initiate the Faith and Action (FAA) Initiative. UWMB had traditionally only worked with secular organizations. The Faith and Action Initiative was envisioned as funding faith-based programs for youth precisely because of their spiritual impact on participants. Churches—especially Black churches—in some hard-to-reach Boston neighborhoods were serving youth in a way that more traditional agencies were not. FAA would direct small grants to these religious organizations on a trial basis. No grant recipient would be allowed to proselytize. But each would be required to include spiritual transformation in its program as a condition of winning a grant (from Duke case study on FAA).

The Greater Boston Interfaith Organization (GBIO) is an organization of 50 religious congregations and other local institutions that joined together in 1998 in order to more powerfully pursue justice in Massachusetts. Since its founding, GBIO has played a critical role in securing Massachusetts health care reform; helping to roll over $300 million into the construction of affordable housing in the state; and supporting local leadership in efforts to attain worker protections, school renovations, adequate access to school textbooks, as well as other major victories (from GBIO.org).

The Institute for Pastoral Excellence (IEP) was planned and implemented in 2002 as an initiative of the Fellowship of Hispanic Pastors of New England (COPAHNI). COPAHNI is a regional fellowship of Hispanic churches and ministries. The purpose of IEP was to help Hispanic pastors and lay leaders in New England build their foundation for effective and resilient ministry. IEP was funded with two multi-year grants from the Lilly Endowment ($660,000 and $330,000, respectively). IEP maintained strong partnerships with Emmanuel Gospel Center (fiscal agent, consulting, and administrative support) and the Center for Urban Ministerial Education and Vision New England (consulting, speakers, and materials).

In 2004, a group of suburban leaders met with urban leaders to see if we could provide resources so connecting would be easier. “The answer can’t be that you have to talk with Ray Hammond to get connected.” Out of those conversations, CityServe was born. The goal was to create online resources for connecting, coupled with staff support for the process. Harry Howell, president of Leadership Foundations, offered to donate a couple days a week to get this off the ground, and EGC raised some funds and hired a staff person to get things started. Harry, however, had a heart attack and was not able to follow through on his commitment, the project never found its footing in the community or with donors, and the experiment ended in 2007.

In 2004 and 2005 there was a growing sense among many believers that God was about to move powerfully in the New England region. Covenant for New England was formed to promote the functional unity, spiritual vitality, and corporate mindset that would prepare the way for a fresh movement of God’s Spirit. In 2006, Roberto Miranda, Jeff Marks, and others involved inCovenant for New England met with British prayer leader Brian Mills to discuss how to broaden the Covenant network to include all of New England. In February of 2007, the New England Alliance was formed consisting of representatives from all 6 New England states. This group began meeting monthly in various places around the region. One unique aspect of Alliance gatherings was they always began with an hour or two of prayer before any other business was brought up for discussion.

From 2008 to 2010, a multi-ethnic group of urban and suburban church leaders worked together to plan and prepare for the national Ethnic America Network Summit, “A City Without Walls.” The conference was jointly hosted in April 2010 by Jubilee Christian Church International and Morning Star Baptist Church. The Summit featured local speakers (including Dr. Alvin Padilla of CUME and Pastor Jeanette Yep of Grace Chapel) and national speakers with deep Boston roots (including Rev. Dr. Soong-Chan Rah). The Summit brought together many diverse partners and established relationships that last today.

In 2010, Boston Public Schools Superintendent Dr. Carol Johnson created a community liaison position to foster more school partnerships with faith-based and community-based organizations. The opportunity for church/school partnerships led to some significant urban/suburban church partnerships, such as Peoples Baptist/North River, and Global Ministries/Grace Chapel. EGC’s Boston Education Collaborative currently supports about 40 church/school partnerships in Boston.

Greater Things for Greater Boston grew out of the initial desire of several key urban and suburban pastors to see broader connections between pastors and churches in Greater Boston. Central to developing the vision were biennial “Conversations on the Work of God in New England” which highlighted local and national pastors and networks joining with God to do innovative work to reach their city. The first conversation was held in May 2010. Topics have included “Why Cities Matter?”, church/school partnerships, community trauma, and much more. The identity and mission of GTGB is: “We are a diverse network of missional leaders stubbornly committed to one another and to accelerating Christ’s work in Greater Boston.”

There were at least two precursors to Greater Things for Greater Boston. The Boston Vision Group formed in 2001 “to see in the next 5 – 10 years, Boston will be a place where there is infectious Christian Community wherever you turn.” The Greater Boston Social Justice Network, formed in 2004, was “committed to eradicating social injustices that impede the advancement of God’s kingdom on earth.” Both groups included a variety of urban and suburban leaders, and both were active over several years.

In January 2017, EGC and the BMA worked with Jamie Bush and Drake Richey to convene a group of mostly professional under-40s, in the financial district, to consider what God has been doing in Boston over the last 30 years. This led to another meeting of the same group in March to hear from Pastors Ray Hammond and Bryan Wilkerson about what the Bible says about engaging your talents and the needs of society, with small-group discussion, pizza and wine. In May, the group met again at the Dorchester Brewing Company for a discussion of seeking God's purpose for your life and prayer. Again with food (and, of course, beer). Next steps, including hopefully meeting for prayer, are being considered.

New England's Book of Acts

New England’s Book of Acts is a 2007 publication of the Emmanuel Gospel Center that captures the stories of how God has been growing his Church among many people groups and ethnic groups in New England.

WHAT IS IT?

New England’s Book of Acts is a publication of the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) that captures the stories of how God has been growing his Church among many people groups and ethnic groups in New England.

WHERE IS IT?

An online version of the book is available here.

HOW AND WHY WAS IT WRITTEN?

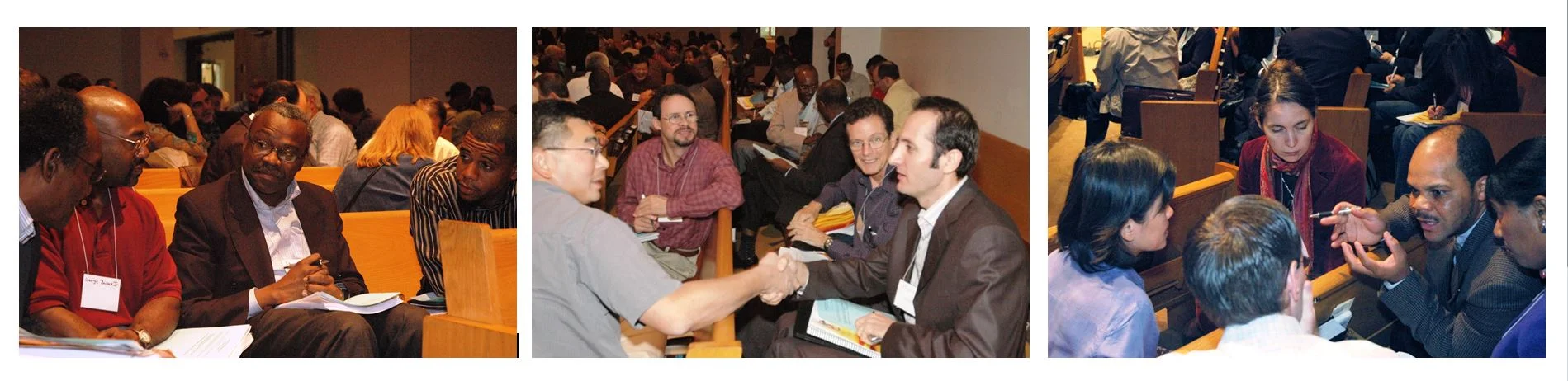

Intercultural Leadership Consultation 2007

Between 2000 and 2007, EGC collaborated with various church groups and leaders to compile stories, articles, and resources that help tell the story of what God is doing in New England. Then on October 20, 2007, EGC convened the Intercultural Leadership Consultation, a one-day conference to share the stories captured in New England’s Book of Acts. Four hundred leaders from over 45 ethnic and people groups around New England gathered to learn and celebrate. These included Christian leaders who were Puerto Rican, Colombian, Haitian, Brazilian, Czech, Egyptian, Malawian, Ugandan, Ghanaian, Liberian, Indian, Bengali, Indonesian, Filipino, Cambodian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Mashpee Wampanoag, and Massachusett Natick Indian. Each participant was given a copy of the book.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Updates. In the ten years since publication, there has been some limited updating and editing to the material, and yet, as time goes by, these organic church systems continue to grow and change, so there are many more stories to be told. As these stories are updated, they will be made available here.

We are currently working on these updates, which will be posted soon. When they are posted, we will add the links:

WHAT’S IN THE ORIGINAL BOOK?

Section One

Section One provides an overview of some of the ways God has worked among people who came to Boston and New England and offers a framework to guide our thinking. Research on past revivals and the current Quiet Revival help us gain perspective and look forward to what God will continue to do here. Hopefully, these articles will expand our vision of the Kingdom of God here in New England.

Some of the topics covered in Section One are:

Seeing the Church with Kingdom Eyes

What is the Quiet Revival?

History of Revivalism in New England

Five Stages of Sustained Revival

Additional helpful resources along this line are:

The Quiet Revival: New Immigrants and the Transformation of Christianity in Greater Boston (2014). Basing much of her research on New England’s Book of Acts, Marilynn Johnson, professor of history at Boston College, has written a 28-page paper on the Quiet Revival which was published in Religion and American Culture, Summer 2014, Vol. 24, No. 2. To read it online, click here.

Section Two

Section Two gives examples of how God is at work among the churches of New England. Many of these 24 reports were written by leaders from within the various groups. Others were produced by the Applied Research staff at EGC. This section also includes reports on multicultural churches, international student ministry, and more. Of course not every church or ministry group has been mentioned in this publication. However, there is enough information for users to connect with many various streams, and inspiration to develop stories on those that are not mentioned here. We would love to hear from you if you pursue research on another group among New England’s church streams.

Section Three

Section Three offers a rich selection of articles on topics like leadership development, evangelism, church planting, youth and second generation ministry, diaspora ministry, and social ministries. Some of these selections describe models of ministry in these areas, while others give nuggets of wisdom from experienced leaders. We hope those who also face similar challenges in developing leadership, reaching youth, and meeting other needs, can use these ideas and models.

TAKE ACTION

Questions? If you have questions about New England’s Book of Acts, don’t hesitate to be in touch. Or if you would like to help us continue telling the story of God’s work through the various people streams in New England, we would love to hear from you.

Understanding Boston's Quiet Revival

What is the Quiet Revival? Fifty years ago, a church planting movement quietly took root in Boston. Since then, the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled. How did this happen? Is it really a revival? Why is it called "quiet?" EGC's senior writer, Steve Daman, gives us an overview of the Quiet Revival, suggests a definition, and points to areas for further study.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 94 — December 2013 - January 2014

Introduced by Brian Corcoran

Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

Boston’s Quiet Revival started nearly 50 years ago, bringing an unprecedented and sustained period of new church planting across the city. In 1993, when the Applied Research team at the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began to analyze our latest church survey statistics and realized how extensive church planting had been during the previous 25 years, resulting in a 50% net increase in the number of churches, Doug Hall, president, coined the term, “Quiet Revival.” This movement, he later wrote, is “a highly interrelated social/spiritual system” that does not function “in a way that lends itself to a mechanistic form of analysis.” That is why, he theorized, we could not see it for years.* Perhaps because it was so hard to see, it also has been hard to understand all that is meant by the term.

One of the most obvious evidences of the Quiet Revival is that the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled since 1965. Starting with that one piece of evidence, Steve Daman, EGC’s senior writer, has been working on a descriptive definition of the Quiet Revival. It is our hope that launching out from this discussion and the questions Steve raises, more people can grow toward shared understanding and enter into meaningful dialog about this amazing work of God. We also hope that more can participate in fruitful ministries that are better aligned with what God has done and is continuing to do in Boston today. And thirdly, we want to inspire thoughtful scholars who will identify intriguing puzzles which will prompt additional study.

*Hall, Douglas A. and Judy Hall. “Two Secrets of the Quiet Revival.” New England’s Book of Acts. Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007. Accessed 01/24/14.

What is the Quiet Revival?

by Steve Daman, Senior Writer, Emmanuel Gospel Center

What is the Quiet Revival? Here is a working definition:

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

What questions come to mind when you read this description? To start, why did we choose the words: “unprecedented”, “sustained”, “Christian growth”, and “1965”? Can we defend or define these terms? Or what about the terms “revival” and “quiet”? What do we mean? And what might happen to our definition if the revival, if it is a revival, “persists” for more than “five decades”? How will we know if it ends?

These are great questions. But before we try to answer a few of them, let’s add more flesh to the bones by describing some of the outcomes that those who recognize the Quiet Revival attribute to this movement. These outcomes help us to ponder both the scope and nature of the movement:

The number of churches in Boston has nearly doubled since 1965, though the city’s population is about the same now as then.

Today, Boston’s Christian church community is characterized by a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership.

The spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe.

From these we can infer more questions, but the overarching one is this: “How do we know?” Surely we can verify the numbers and defend the first statement regarding the number of churches, but the following assertions are harder to verify. How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? The implication is that these characteristics are valid evidences for a revival and that they have appeared or grown since the start of the Quiet Revival. Further, has “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival… spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”? What evidence is there? If these assertions are true, then indeed we have seen an amazing work of God in Boston, and we would do well to carefully consider how that reality shapes what we think about Boston, what we think about the Church in Boston, and how we go about our work in this particular field.

Numbers tell the story

The chief indicator of the Quiet Revival is the growth in the number of new churches planted in Boston since 1965. The Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) began counting churches in 1969 when we identified 300 Christian churches within Boston city limits. The Center conducted additional surveys in 1975, 1989, and 1993.1 When we completed our 1993 survey, our statistics showed that during the 24 years from 1969 to 1993, the total number of churches in the city had increased by 50%, even after it overcame a 23% loss of mainline Protestant churches and some decline among Roman Catholic churches.

That data point got our attention. At a time when people were asking us, “Why is the Church in Boston dying?” the numbers told a very different story.

Just four years before the discovery, when we published the first Boston Church Directory in 1989, we saw the numbers rising. EGC President Doug Hall recalls, “As we completed the 1989 directory and began to compile the figures, we were amazed to discover that something very significant was occurring. But it wasn’t until our next update in 1993 that we knew conclusively that the number of churches had grown—and not by just 30 percent as we had first thought, but by 50 percent! We had been part of a revival and did not know it.”2 It was then Doug Hall coined the term, the Quiet Revival.

Fifty-five new churches had been planted in the four years since the previous survey, bringing the 1993 total to 459. EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote at the time, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.”3

In the 20 years since then, church planting has continued at a robust rate. EGC’s count for 2010 was 575, showing a net gain since the start of the Quiet Revival of 257 new churches. The Applied Research staff at the Center is now in the beginning stages of a new city-wide church survey. Already we have added more than 50 new churches to our list (planted between 2008 and 2014) while at the same time we see that a number of churches have closed, moved, or merged. It seems likely from these early indicators that the number of churches in Boston has continued to increase, and the total for 2014 will be larger than the 575 we counted in 2010, getting us even closer to that seductive “doubling” of the number since 1965, when there were 318 churches.4

Regardless of where we go with our definition, what terms we use, and what else we may discover about the churches in Boston, this one fact is enough to tell us that God has done something significant in this city. We have seen a church-planting movement that has crossed culture, language, race, neighborhood, denomination, economic levels, and educational qualifications, something that no organization, program, or human institution could ever accomplish in its own strength.

Defining terms

Let’s return to our working definition and consider its parts.

The Quiet Revival is an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting for nearly five decades so far.

“Quiet”

The term “quiet” works well here because of its obvious opposite. We can envision “noisy” revivals, very emotional and exciting local events where participants may experience the presence of the Holy Spirit in powerful ways. If something like that is our mental model of revival, then to classify any revival as “quiet” immediately gets our attention and tempts us to think that maybe something different is going on here. How or why could a revival be quiet?

In this case, the term “quiet” points to the initially invisible nature of this revival. Doug Hall used the term “invisible Church” in 1993, writing that researchers tend “to document the highly visible information that is pertinent to Boston. We also want to go beyond the obvious developments to discover a Christianity that is hidden, and that is characteristically urban. By looking past the obvious, we have discovered the ‘invisible Church.’”5

An uncomfortable but important question to ask is, “From whom was it hidden?” If we are talking about a church movement starting in 1965, we can assume that the majority of people who may have had an interest in counting all the churches in the city—people like missiological researchers, denominational leaders, or seminary professors—were probably predominantly mainline or evangelical white people. This church-planting movement was hidden, EGC’s Executive Director Jeff Bass says, because “the growth was happening in non-mainline systems, non-English speaking systems, denominations you have never heard of, churches that meet in storefronts, churches that meet on Sunday afternoons.”6

Jeff points out that EGC had been working among immigrant churches since the 1960s, recognizing that God was at work in those communities. “We felt the vitality of the Church in the non-English speaking immigrant communities,” he says. Through close relationships with leaders from different communities, beginning in the 1980s, EGC was asked to help provide a platform for ministers-at-large who would serve broadly among the Brazilian, the Haitian, and the Latino churches. “These were growing communities, but even then,” Jeff says, “these communities weren’t seen by the whole Church as significant, so there was still this old way of looking at things.”7 Even though EGC became totally immersed in these diverse living systems, we were also blind to the full scale of what God was doing at the time.

Gregg Detwiler, director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, calls this blindness “a learning disability,” and says that many Christian leaders missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston through sociological oversight. “By sociological oversight, I am pointing to the human tendency toward ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism is a learning disability of evaluating reality from our own overly dominant ethnic or cultural perspective. We are all susceptible to this malady, which clouds our ability to see clearly. The reason many missed seeing the Quiet Revival in Boston was because they were not in relationship with where Kingdom growth was occurring in the city—namely, among the many and varied ethnic groups.”8

The pervasive mental model of what the Church in Boston looks like, at least from the perspective of white evangelicals, needs major revision. To open our arms wide to the people of God, to embrace the whole Body of Christ, whether we are white or people of color, we all must humble ourselves, continually repenting of our tendency toward prejudice, and we must learn to look for the places where God, through his Holy Spirit, is at work in our city today.

We not only suffer from sociological oversight, Gregg says, but we also suffer from theological oversight. “By theological oversight I mean not seeing the city and the city church in a positive biblical light,” he writes. “All too often the city is viewed only as a place of darkness and sin, rather than a strategic place where God does His redeeming work and exports it to the nations.” The majority culture, especially the suburban culture, found it hard to imagine God’s work was bursting at the seams in the inner city. Theological oversight may also suggest having a view of the Church that does not embrace the full counsel of God. If some Christians do not look like folks in my church, or they don’t worship in the same way, or they emphasize different portions of Scripture, are they still part of the Body of Christ? To effectively serve the Church in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center purposes to be careful about the ways we subconsciously set boundaries around the idea of church. We are learning to define “church” to include all those who love the Lord Jesus Christ, who have a high view of Scripture, and who wholeheartedly agree to the historic creeds.

If we can learn to see the whole Church with open eyes, maybe we can also learn to hear the Quiet Revival with open ears, though many living things are “quiet.” A flower garden makes little noise. You cannot hear a pumpkin grow. So, too, the Church in Boston has grown mightily and quietly at the same time. “Whoever has ears to hear,” our Lord said, “let them hear” (Mark. 4:9 NIV).

“Revival”

What is revival? A definition would certainly be helpful, but one is difficult to come by. There are perhaps as many definitions as there are denominations. All of them carry some emotional charge or some room for interpretation. Yet the word “revival” does not appear in the Bible. As we ask the question: “Is the Quiet Revival really a revival?” we need to find a way to reach agreement. What are we looking for? What are the characteristics of a true revival?

Tim Keller, founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City, has written on the subject of revival and offers this simple definition: “Revival is an intensification of the ordinary operations of the work of the Holy Spirit.” Keller goes on to say it is “a time when the ordinary operations of the Holy Spirit—not signs and wonders, but the conviction of sin, conversion, assurance of salvation and a sense of the reality of Jesus Christ on the heart—are intensified, so that you see growth in the quality of the faith in the people in your church, and a great growth in numbers and conversions as well.”9 This idea of intensification of the ordinary is helpful. If church planting is ordinary, from an ecclesiological frame of reference, then robust church planting would be an intensification of the ordinary, and thus a work of God.

David Bebbington, professor of history at the University of Stirling in Scotland, states in Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts, that there are several types or “patterns” of revival. First, revival commonly means “an apparently spontaneous event in a congregation,” usually marked by repentance and conversions. Secondly, it means “a planned mission in a congregation or town.” This practice is called revivalism, he notes, “to distinguish it from the traditional style of unprompted awakenings.” Bebbington’s third pattern is “an episode, mainly spontaneous, affecting a larger area than a single congregation.” His fourth category he calls an awakening, which is “a development in a culture at large, usually being both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” In summary, “revivals have taken a variety of forms, spontaneous or planned, small-scale or vast.”10

These are helpful categories. Using Bebbington’s analysis, we would say the Quiet Revival definitely does not fit his first and second patterns, but rather fits into his third and fourth patterns. The Quiet Revival was mainly spontaneous. While we can assume there was planning involved in every individual church plant, the movement itself was too broad and diverse to be the result of any one person’s or one organization’s plan. The Quiet Revival seems to have emerged from the various immigrant communities across the city simultaneously, and has been, as Bebbington says, “both wider and longer than other episodes of this kind.” The Quiet Revival was and is vast, city-wide, regional, and not small-scale.

Since at least the 1970s, and maybe before that, many people have proclaimed that New England or Boston would be a center or catalyst for a world-wide revival, or possibly one final revival before Christ’s return. But even that prophecy, impossible to substantiate, is hard to define. What would that global revival actually look like? Scripture seems to affirm that the Church grows best under persecution. That is certainly true today. Missionary author and professor Nik Ripken11 has chronicled the stories of Christians living in countries where Christianity is outlawed and gives remarkable testimony to the ways the Church thrives under persecution. Yet it would seem that what people describe or hope for when they talk about revival in Boston has nothing to do with persecution or hardship.

Dr. Roberto Miranda, senior pastor of Congregación León de Judá in Boston, has revival on his mind. In addition to a recent blog on his church’s website reviewing a book about the Scottish and Welsh revivals, he spoke in 2007 on his vision for revival in New England.12 Despite the fact that few agree on what revival looks like and what we should expect, should God send even more revival to Boston, the subject is always close at hand.

Again, it is interesting that so many Christians would miss seeing the Quiet Revival when there were so many voices in the Church predicting a Boston revival during the same time frame. Many of them, no doubt, are still looking.

“unprecedented”

As mentioned earlier, EGC’s Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell wrote in 1993, “Since 1968 at least 207 new churches have started in Boston. This is undoubtedly more new church starts than in any other 25-year period in Boston’s history.” What Rudy wrote in 1993 continues to be true today, as it appears the rate of church planting has not fallen off since then. Never before has Boston seen such a wave of new church development. God, indeed, has been good to Boston.

“sustained”

The EGC Applied Research team will be able to assess whether or not the Quiet Revival church planting movement is continuing once we complete our 2014 survey. It is remarkable that the Quiet Revival has continued for as long as it has. The next question to consider is “why?” What are the factors that have allowed this movement to continue for so long unabated? What gives it fuel? We may also want to know who are the church planters today, and are they in some way being energized by what has gone on during the previous five decades?

Rev. Ralph Kee, a veteran Boston church planter, and animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, wants to see new churches be “churches that plant churches that plant churches.” He says we need to put into the DNA of a new church this idea that multiplication is normal and expected. He has documented the genealogical tree of one Boston church planted in 1971 that has since given birth to hundreds of known daughter and granddaughter and great-granddaughter churches. Is the Quiet Revival sustained because Boston’s newest churches naturally multiply?

Another reason the Quiet Revival has continued for decades may be the introduction of a contextualized urban seminary into the city as the Quiet Revival was gaining momentum. EGC recently published an interview with Rev. Eldin Villafañe, Ph.D., the founding director of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), the Boston campus of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and a professor of Christian social ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Dr. Villafañe confirmed CUME was shaped by the Quiet Revival. But as both are interconnected living systems, CUME also shaped the revival, giving it depth and breadth.

“One of the problems with revivals anywhere,” Dr. Villafañe points out, “is oftentimes you have good strong evangelism that begins to grows a church, but the growth does not come with trained leadership, educated biblically and theologically. You can have all kinds of problems. Besides heresy, you can have recidivism, people going back to their old ways. The beautiful thing about the Quiet Revival is that just as it begins to flourish, CUME is coming aboard.”13

CUME was in place as a contextualized urban seminary to “backfill theology into the revival,” as Jeff Bass describes it, training thousands of local, urban leaders since 1976, with 300 students now attending each year.

“Christian growth”

We use the words “Christian growth” rather than “church growth” for a reason. We want to move our attention beyond the numbers of churches to begin to comprehend how these new churches may have influenced the city. Surely it is not only the number of churches that has grown. The number of people attending churches has also grown. One of the goals of the EGC Applied Research team is to document the number of people attending Boston’s churches today.14

But as we look beyond the number of churches and the number of people in those churches, we also want to see how these people have impacted the city. “Christians collectively make a difference in society,”15 says Dana Robert, director of the Center for Global Christianity and Mission at Boston University. Exploring and documenting the ways that Christians in Boston have made an impact on the city, showing ways the city has changed during the Quiet Revival, would be an important and valuable contribution to the ongoing study of Christianity in Boston.

“city of Boston”

We mean something very specific when we say “the city of Boston.” As Rudy Mitchell pointed out in the April 2013 Issue of the Review, one needs to understand exactly what geographical boundaries a particular study has in mind. “Boston” may mean different things. “This could range from the named city’s official city limits, to its county, metropolitan statistical area, or even to a media area covering several surrounding states.” Regarding the Quiet Revival, we mean Boston’s official city limits which today include distinct neighborhoods such as Roxbury, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, East Boston, etc., all part of the city itself.

Boston’s boundaries have not changed during the Quiet Revival, but when we have occasion to look further back into history and consider the churches active in Boston in previous generations, we need to adjust the figures according the where the city’s boundary lines fell at different points in history as communities were absorbed into Boston or as new land was claimed from the sea.

EGC’s data gathering and analysis is, for the most part, restricted to the city of Boston, as we have described it. However, the Center’s work through our various programs often extends beyond these boundaries through relational networks, and we see the same dynamics at work in other urban areas in Greater Boston and beyond. It would be interesting to compare the patterns of new church development among immigrant populations in these other cities with what we are learning in Boston. There is, for example, some very interesting work being done on New York City’s churches on a Web site called “A Journey Through NYC Religions” (http://www.nycreligion.info/).

“1965”

We chose 1965 as a start date for the Quiet Revival for two reasons. First, there seems to be a change in the rate of new church plants in Boston starting in 1965. Of the 575 churches active in Boston in 2010, 17 were founded throughout the 1950s, showing a rate of less than 2 per year. Seven more started between 1960 and 1963 while none were founded in 1964, still progressing at a rate of less than 2 per year. Then, over the next five years, from 1965 to 1969, 20 of today’s churches were planted (averaging 4 per year); about 40 more were launched in the 1970s (still 4 per year), 60 in the 1980s (averaging 6 per year), 70 in the 1990s (averaging 7 per year), and 60 in the 2000s (6 per year). Again, we are counting only the churches that remain until today. A large number of others were started and either closed or merged with other churches, so the actual number of new churches planted each year was higher.

Another reason for choosing 1965 as the start date was that the Immigration Act of 1965 opened the door to thousands of new immigrants moving into Boston. Our research shows that the majority of Boston’s new churches were started by Boston’s newest residents, and that that trend continued for years. For example, of the 100 churches planted between 2000 and 2005, about 15% were Hispanic, 10% were Haitian, and 6% were Brazilian. At least 5% were Asian and another 7% were African. Not more than 14 of the 100 churches planted during those years were primarily Anglo or Anglo/multiethnic. The remaining 40 to 45% of new churches were African American, Caribbean or of some other ethnic identity.

Throughout the first few decades of the Quiet Revival, most, but not all new church development occurred within the new immigrant communities. At the same time many immigrant communities experienced significant growth in Boston, the African American population was also growing, showing an increase of 40% between 1970 and 1990. Between 1965 and 1993, although 39 African American churches closed their doors, well over 100 new ones started, for a net increase of about 75 churches. Among today’s total of 140 congregations with an African American identity, 57 were planted during those early years of the Quiet Revival between 1965 and 1993. Many of these churches have grown under skilled leadership to be counted among the most influential congregations in Boston, and new Black churches continue to emerge.

The year 1965 was a year of much change. While we point to these two specific reasons for picking this start date for the Quiet Revival (the change in the rate of church planting in Boston and the Immigration Act of 1965), there were other movements at play. A charismatic renewal began to sweep across the country at that time starting in the Catholic and Episcopal communities on the West Coast. Close on its heels was the Jesus Movement. Vatican II, which was a multi-year conference, coincidentally closed in 1965, bringing sweeping changes to the Roman Catholic community. Socially, the civil rights movement was front and center during those years.

It seems obvious from the evidence of who was planting churches that one of the main influencing factors was the Pentecostal movement among the immigrant communities. It may also be helpful to explore some of the other cultural movements occurring simultaneously to see if other influences helped to fan the flames. We may discover that in addition to immigration factors, various other streams—whether cultural, Diaspora, theological, or social—were used by God to facilitate the growth of this movement.

Boston’s population

Some may wrongly assume that the growing number of new churches in Boston must relate to a growing population. This is certainly not true of Boston. The population of the city of Boston was 616,326 in 1965 and forty-five years later, in 2010, was very nearly the same at 617,594. During those years, however, the population actually declined by more than 50,000 to 562,994 in 1980. This shows that this remarkable increase in the number of churches is not the result of a much larger population.

While the population total was about the same in 2010 as it was in 1965, the makeup of that population has changed dramatically through immigration and migration, and this is a very significant factor in understanding the Quiet Revival.

One issue that still needs to be addressed is Boston’s church attendance in proportion to the population. Based on our current research and over 40 years’ experience studying Boston’s church systems, we estimate that this number has increased from about 3% to as much as perhaps 15% during this period. EGC is preparing to conduct additional comprehensive research to accurately assess the percentage of Bostonians who attend churches.

The other indicators

How do we know there is “a growing unity, increased prayer, maturing church systems, and a strong and trained leadership”? What evidence is there that “the spiritual vitality of churches birthed during the Quiet Revival has spread, igniting additional church development and social ministries in the region and across the globe”?

The work required to clearly document and defend these statements is daunting. These issues are important to the Applied Research staff, and we welcome assistance from interested scholars and researchers to help us further develop these analyses. In a future edition of this journal, we may be able to start to bring together some evidences to support these assertions, but we do not have the time or space to do more than to give a few examples here.

We have compiled information relevant to each of these specific areas. For example, we have evidence of more expressions of unity among churches and church leaders, such as the Fellowship of Haitian Evangelical Pastors of New England. We continue to discover more collaborative networks, and more prayer movements, such as the annual Greater Boston Prayer Summit for pastors, which began in 2000. We can point to churches and church systems that have grown to maturity and are bearing much fruit in both the proclamation of the Gospel and in social ministries, such as the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. We are aware of several excellent organizations and schools where leaders may be trained and grow in their skills, in knowledge, and in collaborative ministry.16

For the staff of EGC, this is all far more than an academic exercise. We work in this city and many of us make it our home as well. It is a vibrant and exciting place to be, precisely because the Quiet Revival has changed this city on so many levels. Doug and Judy Hall, EGC’s president and assistant to the president, have been serving in Boston at EGC since 1964, and they have observed these changes. A number of others on our staff have also been working among these churches for decades, including Senior Researcher Rudy Mitchell, who started studying churches and neighborhoods in 1976. Doug Hall says that in the 1960s, it was hard to recommend many good churches, ones for which you would have some confidence to suggest to a new believer or new arrival. Not so today. Today in Boston there are many, many healthy and vibrant churches to choose from all across the city. Our understanding of the Quiet Revival is not only a matter of statistics, it is our actual experience as our work puts us in a position to constantly interact with church leaders representing many different communities in the city.

It appears from this vantage point that the rate of church planting in Boston continues to be robust as we approach the 50-year mark for the Quiet Revival. We are looking forward with excitement to see what the new numbers are when the 2014 church survey is complete. It also appears from the many evidences gained through our relational networks across Boston that these additional indicators of the Quiet Revival also continue to grow stronger.

Notes

(If the resources below are not linked, it is because in 2016 we migrated from EGC’s old website to a new site, and not all documents and pages have been posted. As we are able, we will repost articles from the Emmanuel Research Review and link those that are mentioned below. If you have questions, please click the Take Action button below and Contact Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher.)

1We have written in previous issues about these surveys. See the following editions of the Emmanuel Research Review: No. 18, June 2006, Surveying Churches; No. 19, July/August 2006, Surveying Churches II: The Changing Church System in Boston; No. 21, October 2006, Surveying Churches III: Facts that Tell a Story.

2Daman, Steve. “1969-2005: Four Decades of Church Surveys.” Inside EGC 12, no. 5 (September-October, 2005): p. 4.

3Mitchell, Rudy. “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches.” in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-14.

4We estimate the number of churches in 1965 was 318, based on information derived from Polk’s Boston City Directory (https://archive.org/details/bostondirectoryi11965bost) for that year and adjusted to include only Christian churches. In 1965, many small, newer African American churches were thriving in low-cost storefronts and many of the smaller neighborhood mainline churches had not yet closed or moved out of the city (but many soon would). While there were not yet many new immigrant churches, the city's African American population was growing very significantly and also expanding into new neighborhoods where new congregations were needed.

5Hall, Douglas A., from the Foreword to the section entitled “A Portrait of Boston’s Churches” by Rudy Mitchell, in Hall, Douglas, Rudy Mitchell, and Jeffrey Bass. Christianity in Boston: A Series of Monographs & Case Studies on the Vitality of the Church in Boston. Boston, MA, U.S.A: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 1993. p. B-1.

6Daman, Steve. “EGC’s Research Uncovers the Quiet Revival.” Inside EGC 20, no. 4 (November-December 2013): p. 2.

7Ibid.

8Emmanuel Research Review, No. 60, November 2010, There’s Gold in the City.

9Keller, Tim. “Questions for Sleepy and Nominal Christians.” Worldview Church Digest, March 13, 2013. Web. Accessed January 27, 2014.

10Bebbington, D W. Victorian Religious Revivals: Culture and Piety in Local and Global Contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. p.3.

11Ripken, Nik. personal website. n.d. http://www.nikripken.com/

12Miranda, Roberto. “A vision for revival in New England.” April 7, 2006. Web.

13Daman, Steve. “The City Gives Birth to a Seminary.” Africanus Journal Vol. 8, No. 1, April 2016, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, Center for Urban Ministerial Education. p. 33.

14We wrote about the difficulties national organizations have in coming up with that figure in a previous edition of the Review: No. 88, April 2013, “Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Greater Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical?”

15Dilley, Andrea Palpant. “The World the Missionaries Made.” Christianity Today 58, no. 1 (January/February 2014): p. 34. Web. Accessed: January 30, 2014. Dilley quotes Robert at the end of her article on the impact some 19th century missionaries had shaping culture in positive ways.

16A number of educational opportunities for church leaders are listed in the Review, No. 70, Sept 2011, “Urban Ministry Training Programs & Centers.”

TAKE ACTION

We have mentioned throughout this article that we would welcome scholars, researchers, and interns who could help contribute to our understanding of this movement in Boston.

Note: Some document links might connect to resources that are no longer active.

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge

![Hidden Treasures: Celebrating Refugee Stories [photojournal]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1512579164575-AKNVCYX4Q5DW8IN2CNYP/P1070998.jpg)

![Connecting Multi-Site Church Leaders [PhotoJournal]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1513116581077-WOWU94O437SJAKKAMZMA/DSC_0438-for-header.jpg)

![Ethiopian Churches in Greater Boston [map]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1506113852983-TSLLC1FENTJJGZYIO7MM/orthodox+cross+church.jpeg)

![Beyond Church Walls: What Christian Leaders Can Learn from Movement Chaplains [Interview]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1550010291251-EVMN3KQ15A70OBTAD4JQ/movement-chaplaincy_outdoorcitygroup.jpg)

What is the Quiet Revival? Fifty years ago, a church planting movement quietly took root in Boston. Since then, the number of churches within the city limits of Boston has nearly doubled. How did this happen? Is it really a revival? Why is it called "quiet?" EGC's senior writer, Steve Daman, gives us an overview of the Quiet Revival, suggests a definition, and points to areas for further study.