BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

The Journey for Justice: How Lament Powers Repair

Liza Cagua-Koo shares her perspective on pursuing God's ways of dealing with pain through lament as the strong foundation from which we can engage productively and perseveringly in the work of repair.

The Journey for Justice: How Lament Powers Repair

We are a world in tremendous pain, and as we convulse with it in our inner being, Jesus is standing at the door knocking. His spirit is knocking urgently at the door of the church, his Body. He's here, looking for the sick and those who welcome resurrection. We are each individually and through our local expressions of church now making decisions to answer that knock, or not.

Pursuing God's ways of dealing with pain through lament are the strong foundation from which we can engage productively and perseveringly in the work of justice and healing. Unless we figure out what to do with pain in an ongoing way, we won't last in the cross-bearing partnership Jesus is calling us into.

Unless we figure out what to do with pain in an ongoing way, we won't last in the cross-bearing partnership Jesus is calling us into.

In this 3-part series I will share what I’m learning about running a marathon against injustice, and the interrelated centrality of pain, lament and repair. This first reflection attempts to bring some texture to the pain I am seeing in others and in myself.

We Are in Pain

We are in pain. I bear witness to it here, in my limited way, and pour out my anguished cry out before God now and in the presence of those who might have an ear to hear.

Selah.

There is a pain that no human can really hold consciously in its fullness: the depth of the suffering of even one person who faces chronic systemic dehumanization from white supremacy culture and systems. Only God can fully bear the parental soul pain of having "the talk", the bone-deep exhaustion of the black tax, the mental trauma of being continuously gaslit when you've tried to name the systemic pattern throughout your life, and for generations.

This is the pain of fighting to honor your imago dei when your experience at school, at the doctor's office, with the loan officer, or with the police, screams otherwise. And now, in this unexpected moment opened up by the straw-break of one horrifying video, there is the jolting pain of seeing the world you've been living in suddenly perceived by those on the outside.

And as this other world outside your door seems to be waking, as white strangers kneel along a funeral route honoring George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, as targeting systemic injustice becomes a thing, there is the pain of daring to hope that this will lead to something. And another kind of suffering manifests: the pain of figuring out a new way to be and to lead, in the face of eager white folks wanting to make it all better but not ready to face the cost to them of what repair might entail.

Selah.

There is another kind of pain: the pain of having your understanding of the world blown up into cinders. The pain of deconstructing a comforting world that has rested on the myth of meritocracy, on the myth of American exceptionalism, and the misguided understanding that there are good and bad people in the world and all rests on individual choices, untethered from systems and their behavior. The pain of betrayal of where you put your trust (your parents, your schooling, your history), and worse: the pain of sensing some level of responsibility now that you know something is deeply wrong.

And when, finally, you come to terms with this new world, and decide to step forth into the struggle against systemic injustice, there is the pain of not knowing what to do, of making mistakes, of having your good intentions mean very little in the face of the impact of your actual choices. Here too is the pain of not knowing where to take your pain, because the world that has been oppressed does not have room for it.

Selah.

And there's the kind of pain I know best: the pain of being part of a group dehumanized by white supremacy while at the same time cooperating with white supremacy in order to survive it.

This is a diverse nexus with many kinds of pain and expressions. The pain of white-presenting Latinos who've gone along with being "white" and have let go of their roots. The pain of non-white-presenting Latinos who've gone along with being tokens. The pain of black-presenting Latinos marginalized within their own community because of colorism and anti-blackness in it. The pain of seeing other people of color (POC) weaponized against our efforts for justice. The pain of seeing POC standing on the sidelines of those efforts, like when recent immigrants are quick to separate ourselves from historically disenfranchised groups here and distance ourselves from their cause.

I well remember my first cries at school in Boston of "I'm Colombian! I'm not Puerto Rican!" when my 8-year-old mind subconsciously tuned into that demonic wavelength broadcasting that Puerto Ricans were less than, as I witnessed my white teachers routinely chastising them and expecting little from them. So much pain that the disease of white supremacy has caused the non-white immigrant communities as it has dehumanized and divided. And as if that was not hard enough, there's the pain of coming to terms with the fact that we were also carriers, that the infection of racial/ethnic hierarchy was spread by us too.

Selah.

There is great pain amongst POC when we've left each other behind. The pain is not just between white and black, it's amongst us all.

The pain of indigenous people: decimated, blamed for their community's uphill battles—and mostly forgotten by other POC and whites alike as we fight for resources on their ancestral lands. There is the pain of Southeast Asian immigrant communities left behind, invisibly falling short of the ridiculous "model minority myth," their youth in battle with other kids of color in the fight for street cred, looking for respect where it can be found. There is much pain in the realization that we are often just fighting each other for crumbs in the heirarchy of the white supremacy table.

Selah.

What can be done with all this pain—these "tips" and the icebergs that they represent? So many of us have trained ourselves to not look at such horrors, to ignore them, to overcome by focusing on what we think we can do and control. But regardless of whether any of these different streams resonate with you or not, whatever your story is with injustice, I believe we MUST look at the pain and suffering, that the Spirit beseeches us to stand in its presence and see the extent of the desolation, the valley of dry bones before us corporately.

I believe we MUST look at the pain and suffering, that the Spirit beseeches us to stand its presence and see the extent of the desolation, the valley of dry bones before us corporately.

Only by walking with God's spirit amongst these bones can God begin to transform us into a people who can be cross-bearers in Jesus, into a Body who can prophesy over dry bones, that they—that we—might all come alive and live.

While Ezekiel prophesied with words, I believe we must prophesy with action. Today’s dry bones need the flesh of repair-- actions that have the chance to rehumanize what has been dehumanized, to bring to thriving what has been chronically attacked by the systems we live in. I am convinced that biblical lament is an essential fuel for our prophetic action, what will give us the courage to do what needs to be done. Part II will speak to why that is.

Liza Cagua-Koo

Assistant Director

Liza Cagua-Koo pursues racial justice & healing at home in a Latino-Asian family, at Emmanuel Gospel Center with a multiethnic team of urban ministry practitioners, and in life with her BFFs and church community in Dorchester, MA. She is on the long journey of decolonizing her mind and longs for the day when the church is best known for being an agent of justice in our racialized society. Or the day Jesus comes back and delivers us all. She'll take either.

Learn More

EGC is issuing a series of 1st person reflections in response to the killing of Mr. George Floyd, in the hope that each unique voice might be heard, that we might each speak to the part of the Body that we are nearest to, and that together as a team we might disrupt the sin-cancer of white supremacy and our beloved church’s addiction to simple answers.

5 Mind-Blowing Realities About Race (That White People May Not Know)

Many White people may be surprised by some of the most basic realities of racism in America today. Don’t be one of them—get informed in this article from EGC’s Race & Christian Community initiative REWE, Race Education for White Evangelicals.

5 Mind-Blowing Realities About Race (That White People May Not Know)

by Megan Lietz

Megan Lietz, MDiv, STM, directs Racism Education for White Evangelicals (ReWe), a program of EGC’s Race & Christian Community Initiative. The intended audience of ReWe ministry and writing is White Evangelicals (find out why).

Race is a complicated subject. We’re all at various points of understanding race issues and their impact. I want to share five realities White people may not know that I believe can transform our perspectives about race.

Reality #1. Society—not biology—defines race.

Differences in skin color have existed throughout history. But the meaning we in the U.S. ascribe to skin color is an artificial social construction that emerged in the 17th century—and has changed over time.

No genes are shared by all members of a given race that determine qualities by racial classification. Our experience as racialized beings isn’t defined by our biology, but by our society.

Racial classifications have shifted over time based on the interests and influence of people in power. In the 20th century, Irish, Italian, Greek, Jewish, and Eastern European people were all considered “non-White,” and they experienced discrimination because they were not considered a part of the dominant racial group.

These groups gained privilege only when those in power expanded the definition of Whiteness to include their nationality. Similarly, people of color who petitioned for “White” status were denied it, based on changing—and, at times, contradictory—legal interpretations that allowed White people to define racial classification.

To learn more about how the concept of race is rooted in society, not biology explore this interactive website or this article from National Geographic.

To learn more about how the social construct of race developed over time, click here.

Because society has ascribed meaning to race, inequality is both created and dismantled by working towards societal change.

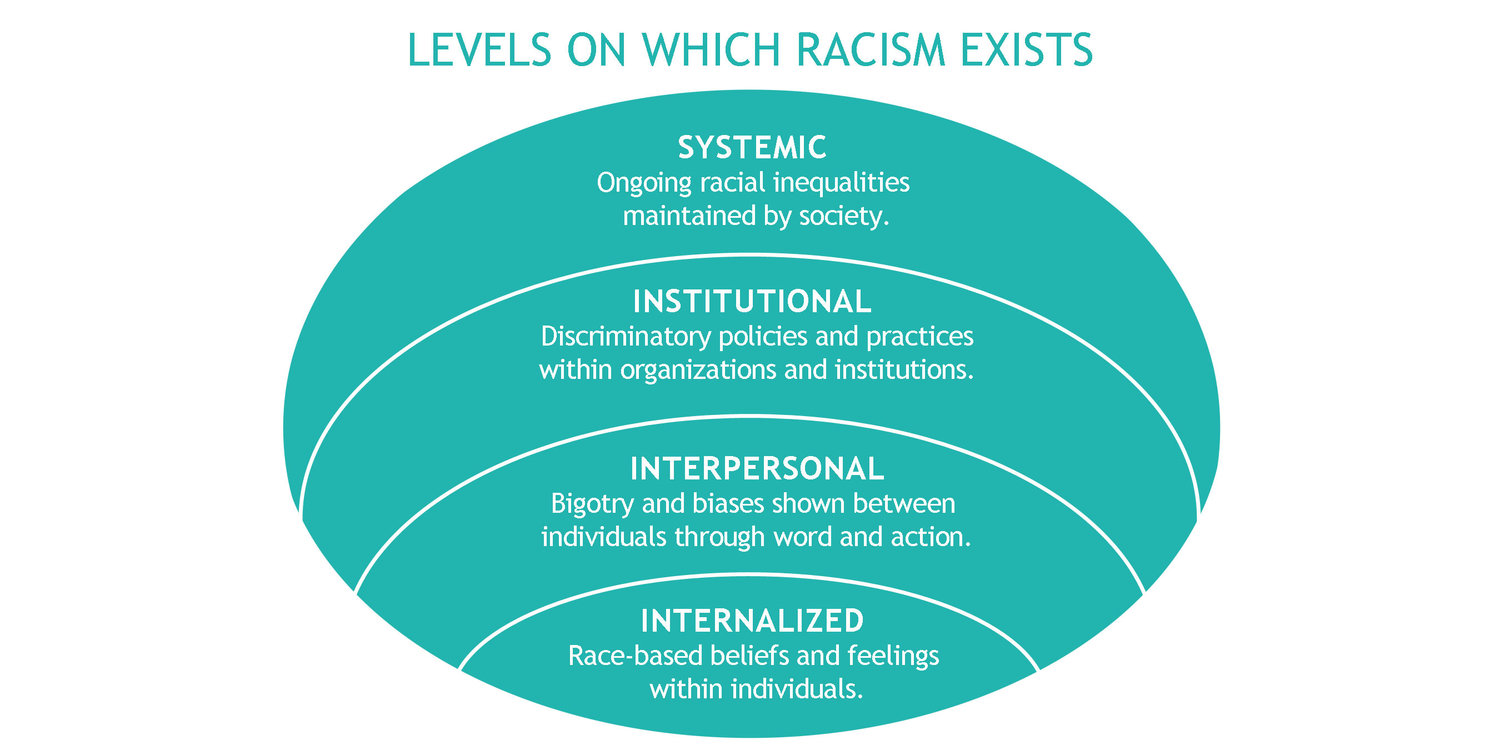

Reality #2. Racism Goes Beyond Interpersonal Interactions

What first comes to mind when you hear the word “racism”? You may picture personal biases or racist interactions between people. While this is one form of racism, organizations and social systems can also take actions that uphold the reality of racism.

Internalized

Race-based beliefs and feelings within individuals.

E.g., consistently believing that your way of doing things is better than that of your colleagues of color.

Interpersonal

Bigotry and biases shown between individuals through word and action.

E.g., leaders exclude people of color from a team because they “just aren’t a good fit with the team dynamic.”

Institutional

Discriminatory policies and practices within organizations and institutions.

E.g., resumes that have Black-sounding names are 50% less likely to get called for an interview compared to people with White-sounding names.

Systemic

Ongoing racial inequalities maintained by society.

E.g., in 2015, the median net worth for White families in the Boston area ($247,500) towered over that of Hispanic ($3,020 for Puerto Ricans, $2,700 for other Hispanics) and Black families ($12,000 for “Caribbean Blacks” and $8 for “U.S. Blacks”). Additionally, in 2014, Asian American individuals in Boston were more than two times as likely to find themselves in poverty compared to their White counterparts.

Total Assets and Net Worth By Race in the Boston Area

Because racism exists on many levels, racism can be at work in dynamics that don’t seem obviously racist. So we can contribute to racism without awareness or intention to do so.

Reality #3. Individuals can have an unintentional racist impact.

There’s false binary thinking in many people’s minds about racism that sounds like this: “Good people aren’t racist, racist people are bad people.” But well-intentioned people can have a racist impact without knowing it. Below are some realities that contribute to unintentional racist impacts.

Systemic racism

As larger social systems perpetuate racism (see Reality #2), people don’t have to be ill-intentioned, or even aware that they are helping these systems to do so. By supporting organizations and systems that contribute to racial injustice, we are complicit in their racist impacts.

Implicit biases

Unconscious personal biases and stereotypes shape how we see and respond to situations. We all have biases that don’t match our explicit beliefs. We may believe God created all people in his image and we should show no favoritism. But our unconscious reactions may not uphold this belief.

For example, we may think that we don’t see Black men any differently than anyone else. But when we’re walking down the street at night, if we find ourselves holding on to our belongings a little tighter when we pass by a Black man, that’s a flag for us that we’re conditioned to see Black men as more dangerous than others.

This test that can help reveal some of your own implicit biases.

Intent vs. Impact

What we say or do can have a different impact than what we mean. Even if we act with the best of intentions, by the time our action is translated through a history of overt discrimination, we may hurt another person in ways we didn’t anticipate.

Example

A Christian leader who lives in a largely White area of the suburbs is motivated to partner with city leaders for broader ministry impact. She enters a gathering with urban leaders who are mostly people of color and proceeds to “school” the city leaders about the importance of collaboration. She is assuming God wasn’t already working in the city in those ways, reinforcing historically degrading narratives about leadership capacity and the gifts of God among people of color. Such assumptions can be offensive to urban leaders of color and have a counterproductive impact, in race relations and beyond.

We are broken people in a broken world. Because we contribute to the problem, we bear a measure of responsibility in helping make things right.

Reality #4. Racism is a daily stressor to people of color.

Racism doesn’t just exist when people of color experience occasional, blatant, intentional racism. Racism profoundly impacts people’s daily experiences, both in everyday interactions and in ongoing disparities.

Subtle Racist Jabs are Commonplace, Accepted

People of color endure slights, indignities, and insults on a regular basis. These may come from people who don’t mean harm, but who don’t have the cultural awareness to know that what they are saying or doing may be hurtful. These incidents are called microaggressions.

For example, asking a person of Asian descent, “Where are you from?” may seem innocent. But remember that they get asked this question—sometimes in hostility—more often than you. The question implies that they aren’t American born. If they are American, it can make them feel like they don’t belong in their homeland, or aren’t welcome. While each incident may seem minor, repeated experiences add up to a demoralizing impact over time. “Did you grow up around here?” is a less presumptuous way to ask the same question.

See this chart of a broad list of microaggressions, what they can subtly communicate, and why they are problematic.

Disparities in Daily Life

People of color endure systemic racial inequalities in their everyday life. For example, a national study reveals that a majority of those in Black communities feel that racism has a negative impact on their daily experiences of neighborhood safety (80%), access to quality public schools (73%), access to financially viable jobs (78%) and access to quality, affordable healthcare (74%).

Take a look at this infographic for more examples and consider the way these realities might impact your life.

Microaggressions and systemic disparities have a demonstrated negative impact on the mental and physical well being of people of color. The stressors created by regular experiences of discrimination have been correlated with and are thought to cause both a measurable psychological burden and long-term adverse health outcomes.

While White people can choose how often to engage with issues related to race, racism is part of the daily experiences and stressors of people of color.

Reality #5. Racism Harms All of Us

Racism is one of the sins the enemy uses to separate people from God and one another.

God created humanity in right relationship with himself and each other. But when sin entered the scene, our relationships became broken, divorced from God’s design. Racism in America idolizes White physical features and White values as supreme over those of others, denying that all people are equally image bearers of God.

The negative impact of racism on White people doesn’t compare to its effects on people of color. But everyone is degraded by a culture sick with sin. Living in a society that elevates White values as supreme over others diminishes White people in the following ways.

As people of a dominant culture, White people may be more likely to do the following:

Be unreflective and unquestioning about our cultural values and assumptions.

Have a diminished capacity to persevere in the face of obstacles or discomfort.

Experience fear, anxiety, guilt, or shame around issues of race, and react in broken ways as a result.

Feel barriers to authentic and intimate relationships with people of color, as well as with White people who have different opinions on race.

Hold an incomplete view of God, as our theology and faith traditions are shaped mostly (or exclusively) by a Euro-American perspective.

Contribute to racial tension, hatred, and violence in our homes, communities, and world.

Have more limited imagination and creativity due to complacency in the status quo.

Have more limited exposure to the enriching cultures, perspectives, and assets of people of color.

Struggle to work across racial lines in addressing shared concerns and contributing to an improved society.

Reflection Question

How have you been diminished by a society that assumes the supremacy of White values?

Conclusion

Racism is one more reminder that we live in a fallen and hurting world—a world where the enemy comes to steal, kill, and destroy in ways we can and can’t see. But with God, there’s hope of redemption. God continues to call humanity back to himself, working to restore the right relationships God intended in creation.

We have much work yet to do. God, through Jesus’ death and resurrection, has redeemed and is redeeming us in our brokenness. God can heal us and make us agents of healing as we invite him to do transformative work in our lives.

Pray with me

Lord, help me to see where I’m blind.

Help me to reflect on what you are showing me, even when it makes me uncomfortable.

Help me to open myself up to your work in me so that I can experience freedom, healing, and wholeness.

Help me to be a part of the restorative work you’re doing in the world. Amen.

Take Action

Racism is complex and multi-layered. If simple answers were enough, racism would not persist as it does today. We believe that growing as an agent of racial healing happens best in a learning community. RCCI cohorts are White evangelicals learning together about race.

Barriers to Mental Health Care for Boston-Area Black Residents [Report]

Does Boston-area mental health care adequately serve Black residents? Community Health Network Area 17 (CHNA 17) invited EGC to partner in addressing this question for six cities near Boston.

Barriers to Mental Health Care for Boston-Area Black Residents [Report]

by the ARC Team

Does Boston-area mental health care adequately serve Black residents? Community Health Network Area 17 (CHNA 17) invited EGC to partner in addressing this question for six cities near Boston.

CHNA 17’s 2018 report cites seven major barriers to American-born Blacks receiving mental health care as needed. Barriers include:

a double-stigma associated with mental health issues in the current social climate

a dearth of Black mental health providers

CAMBRIDGE, MA - Focus group for Cambridge mental health service providers, facilitated by EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting.

SOMERVILLE, MA - Nika Elugardo (left) and Stacie Mickelson (right), former and current Directors, respectively, of EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting co-facilitating a mental health care focus group with Somerville residents.

TAKE ACTION

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge

![Barriers to Mental Health Care for Boston-Area Black Residents [Report]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1518458267039-7WI3NJUWYJQKOQCYDWTK/pexels-photo-561654.jpeg)