BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

5 Mind-Blowing Realities About Race (That White People May Not Know)

Many White people may be surprised by some of the most basic realities of racism in America today. Don’t be one of them—get informed in this article from EGC’s Race & Christian Community initiative REWE, Race Education for White Evangelicals.

5 Mind-Blowing Realities About Race (That White People May Not Know)

by Megan Lietz

Megan Lietz, MDiv, STM, directs Racism Education for White Evangelicals (ReWe), a program of EGC’s Race & Christian Community Initiative. The intended audience of ReWe ministry and writing is White Evangelicals (find out why).

Race is a complicated subject. We’re all at various points of understanding race issues and their impact. I want to share five realities White people may not know that I believe can transform our perspectives about race.

Reality #1. Society—not biology—defines race.

Differences in skin color have existed throughout history. But the meaning we in the U.S. ascribe to skin color is an artificial social construction that emerged in the 17th century—and has changed over time.

No genes are shared by all members of a given race that determine qualities by racial classification. Our experience as racialized beings isn’t defined by our biology, but by our society.

Racial classifications have shifted over time based on the interests and influence of people in power. In the 20th century, Irish, Italian, Greek, Jewish, and Eastern European people were all considered “non-White,” and they experienced discrimination because they were not considered a part of the dominant racial group.

These groups gained privilege only when those in power expanded the definition of Whiteness to include their nationality. Similarly, people of color who petitioned for “White” status were denied it, based on changing—and, at times, contradictory—legal interpretations that allowed White people to define racial classification.

To learn more about how the concept of race is rooted in society, not biology explore this interactive website or this article from National Geographic.

To learn more about how the social construct of race developed over time, click here.

Because society has ascribed meaning to race, inequality is both created and dismantled by working towards societal change.

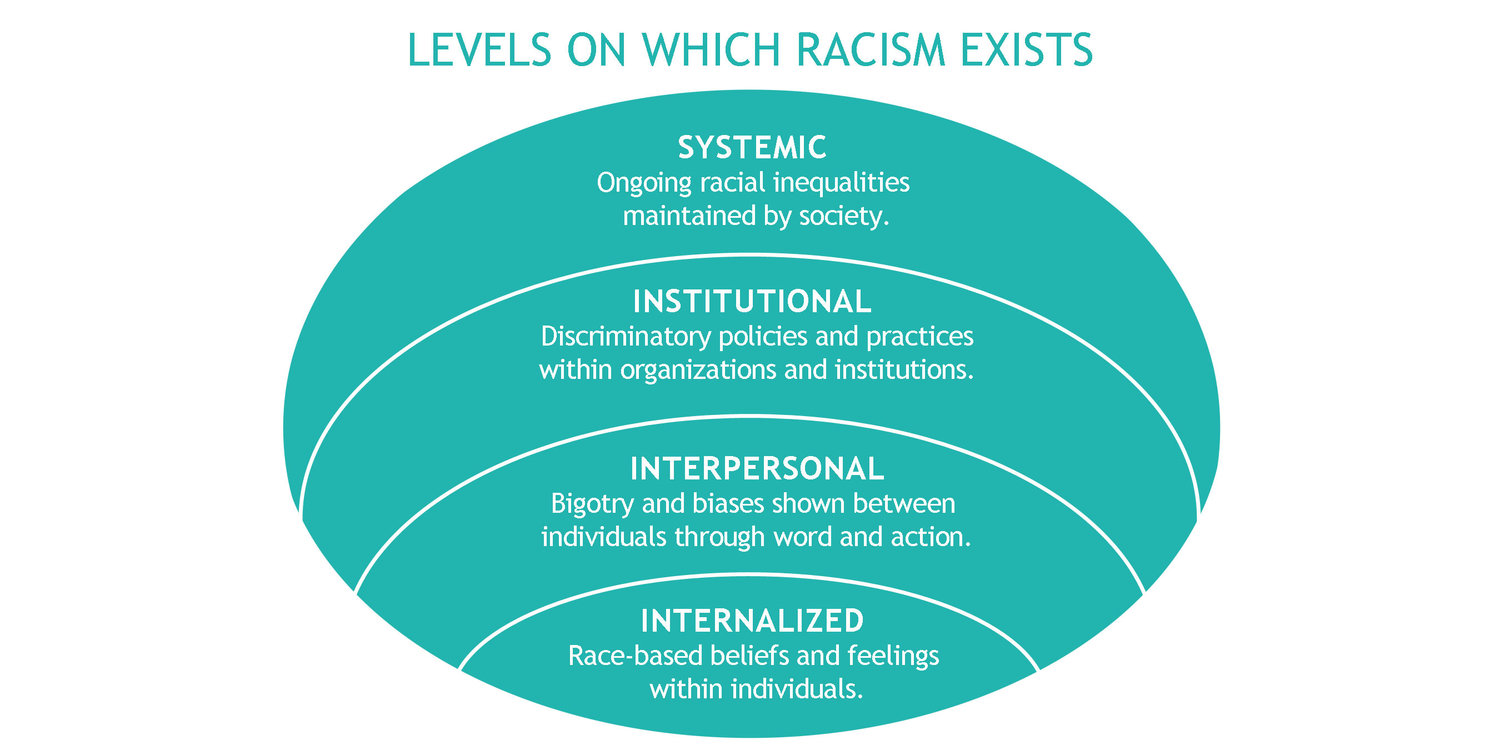

Reality #2. Racism Goes Beyond Interpersonal Interactions

What first comes to mind when you hear the word “racism”? You may picture personal biases or racist interactions between people. While this is one form of racism, organizations and social systems can also take actions that uphold the reality of racism.

Internalized

Race-based beliefs and feelings within individuals.

E.g., consistently believing that your way of doing things is better than that of your colleagues of color.

Interpersonal

Bigotry and biases shown between individuals through word and action.

E.g., leaders exclude people of color from a team because they “just aren’t a good fit with the team dynamic.”

Institutional

Discriminatory policies and practices within organizations and institutions.

E.g., resumes that have Black-sounding names are 50% less likely to get called for an interview compared to people with White-sounding names.

Systemic

Ongoing racial inequalities maintained by society.

E.g., in 2015, the median net worth for White families in the Boston area ($247,500) towered over that of Hispanic ($3,020 for Puerto Ricans, $2,700 for other Hispanics) and Black families ($12,000 for “Caribbean Blacks” and $8 for “U.S. Blacks”). Additionally, in 2014, Asian American individuals in Boston were more than two times as likely to find themselves in poverty compared to their White counterparts.

Total Assets and Net Worth By Race in the Boston Area

Because racism exists on many levels, racism can be at work in dynamics that don’t seem obviously racist. So we can contribute to racism without awareness or intention to do so.

Reality #3. Individuals can have an unintentional racist impact.

There’s false binary thinking in many people’s minds about racism that sounds like this: “Good people aren’t racist, racist people are bad people.” But well-intentioned people can have a racist impact without knowing it. Below are some realities that contribute to unintentional racist impacts.

Systemic racism

As larger social systems perpetuate racism (see Reality #2), people don’t have to be ill-intentioned, or even aware that they are helping these systems to do so. By supporting organizations and systems that contribute to racial injustice, we are complicit in their racist impacts.

Implicit biases

Unconscious personal biases and stereotypes shape how we see and respond to situations. We all have biases that don’t match our explicit beliefs. We may believe God created all people in his image and we should show no favoritism. But our unconscious reactions may not uphold this belief.

For example, we may think that we don’t see Black men any differently than anyone else. But when we’re walking down the street at night, if we find ourselves holding on to our belongings a little tighter when we pass by a Black man, that’s a flag for us that we’re conditioned to see Black men as more dangerous than others.

This test that can help reveal some of your own implicit biases.

Intent vs. Impact

What we say or do can have a different impact than what we mean. Even if we act with the best of intentions, by the time our action is translated through a history of overt discrimination, we may hurt another person in ways we didn’t anticipate.

Example

A Christian leader who lives in a largely White area of the suburbs is motivated to partner with city leaders for broader ministry impact. She enters a gathering with urban leaders who are mostly people of color and proceeds to “school” the city leaders about the importance of collaboration. She is assuming God wasn’t already working in the city in those ways, reinforcing historically degrading narratives about leadership capacity and the gifts of God among people of color. Such assumptions can be offensive to urban leaders of color and have a counterproductive impact, in race relations and beyond.

We are broken people in a broken world. Because we contribute to the problem, we bear a measure of responsibility in helping make things right.

Reality #4. Racism is a daily stressor to people of color.

Racism doesn’t just exist when people of color experience occasional, blatant, intentional racism. Racism profoundly impacts people’s daily experiences, both in everyday interactions and in ongoing disparities.

Subtle Racist Jabs are Commonplace, Accepted

People of color endure slights, indignities, and insults on a regular basis. These may come from people who don’t mean harm, but who don’t have the cultural awareness to know that what they are saying or doing may be hurtful. These incidents are called microaggressions.

For example, asking a person of Asian descent, “Where are you from?” may seem innocent. But remember that they get asked this question—sometimes in hostility—more often than you. The question implies that they aren’t American born. If they are American, it can make them feel like they don’t belong in their homeland, or aren’t welcome. While each incident may seem minor, repeated experiences add up to a demoralizing impact over time. “Did you grow up around here?” is a less presumptuous way to ask the same question.

See this chart of a broad list of microaggressions, what they can subtly communicate, and why they are problematic.

Disparities in Daily Life

People of color endure systemic racial inequalities in their everyday life. For example, a national study reveals that a majority of those in Black communities feel that racism has a negative impact on their daily experiences of neighborhood safety (80%), access to quality public schools (73%), access to financially viable jobs (78%) and access to quality, affordable healthcare (74%).

Take a look at this infographic for more examples and consider the way these realities might impact your life.

Microaggressions and systemic disparities have a demonstrated negative impact on the mental and physical well being of people of color. The stressors created by regular experiences of discrimination have been correlated with and are thought to cause both a measurable psychological burden and long-term adverse health outcomes.

While White people can choose how often to engage with issues related to race, racism is part of the daily experiences and stressors of people of color.

Reality #5. Racism Harms All of Us

Racism is one of the sins the enemy uses to separate people from God and one another.

God created humanity in right relationship with himself and each other. But when sin entered the scene, our relationships became broken, divorced from God’s design. Racism in America idolizes White physical features and White values as supreme over those of others, denying that all people are equally image bearers of God.

The negative impact of racism on White people doesn’t compare to its effects on people of color. But everyone is degraded by a culture sick with sin. Living in a society that elevates White values as supreme over others diminishes White people in the following ways.

As people of a dominant culture, White people may be more likely to do the following:

Be unreflective and unquestioning about our cultural values and assumptions.

Have a diminished capacity to persevere in the face of obstacles or discomfort.

Experience fear, anxiety, guilt, or shame around issues of race, and react in broken ways as a result.

Feel barriers to authentic and intimate relationships with people of color, as well as with White people who have different opinions on race.

Hold an incomplete view of God, as our theology and faith traditions are shaped mostly (or exclusively) by a Euro-American perspective.

Contribute to racial tension, hatred, and violence in our homes, communities, and world.

Have more limited imagination and creativity due to complacency in the status quo.

Have more limited exposure to the enriching cultures, perspectives, and assets of people of color.

Struggle to work across racial lines in addressing shared concerns and contributing to an improved society.

Reflection Question

How have you been diminished by a society that assumes the supremacy of White values?

Conclusion

Racism is one more reminder that we live in a fallen and hurting world—a world where the enemy comes to steal, kill, and destroy in ways we can and can’t see. But with God, there’s hope of redemption. God continues to call humanity back to himself, working to restore the right relationships God intended in creation.

We have much work yet to do. God, through Jesus’ death and resurrection, has redeemed and is redeeming us in our brokenness. God can heal us and make us agents of healing as we invite him to do transformative work in our lives.

Pray with me

Lord, help me to see where I’m blind.

Help me to reflect on what you are showing me, even when it makes me uncomfortable.

Help me to open myself up to your work in me so that I can experience freedom, healing, and wholeness.

Help me to be a part of the restorative work you’re doing in the world. Amen.

Take Action

Racism is complex and multi-layered. If simple answers were enough, racism would not persist as it does today. We believe that growing as an agent of racial healing happens best in a learning community. RCCI cohorts are White evangelicals learning together about race.

Not That Kind of Racism

Well-meaning people can act in ways that have racist impacts they wouldn't want. Don't be one of these people! Learn all you can to avoid being an accidental racist through this heartfelt reflection.

Not That Kind of Racism

How Good People Can Be Racist Without Awareness or Intent

By Megan Lietz

Megan Lietz, MDiv, STM, directs Racism Education for White Evangelicals (ReWe), a program of EGC’s Race & Christian Community Initiative. The intended audience of ReWe ministry and writing is White Evangelicals (find out why).

In the tragedies of Charlottesville, VA, as a White person, it’s easy for me to see such hate and think, “How awful! That’s racist. Thank God I’m not a racist like that.” In doing so, I affirm my sense of being a good moral person and find comfort in the fact that I’m not like those I’m condemning.

In reality, White people cannot separate ourselves from the problem of racism. Even if we consciously reject racism, the biases and behaviors that contribute to and sustain injustice crop up in our actions. Racism persists not because of the hate of a few White supremacists, but because well-intentioned White people regularly contribute to racial inequity in ways that we may not be aware of or intend.

Expanding our View of Racism

Institutional and structural Racism

While interpersonal racism between people is still common, racism occurs as much if not more at the organizational and systemic level, which can be more difficult for White people to recognize.

For example, people with Black-sounding names are 50% less likely to get called for an interview compared to people with White-sounding names. This bias is one of many contributors to vast disparities between the median net worth of White people as compared with Black people or Hispanic people.

Implicit Bias

How we see and respond to situations is shaped by unconscious personal biases and stereotypes. We all have them, and they don’t necessarily align with our explicit beliefs. These can come out in casual interactions that can make people of color feel disrespected or devalued. They can also have a broader impact when shaping the decisions of policymakers, the prescriptions of doctors, or the actions of law enforcement agents.

To perpetuate racism, people don’t have to be ill-intentioned, or even aware they are contributing to injustice. By not actively resisting racist dynamics—and sometimes even by attempting to do so without proper understanding—we can contribute to a system that sustains inequality and racism.

Reflecting On Our Experiences

White people need education and reflection to see how we may be participating in injustice. We must look inward with openness, intentionality, and humility.

I’ve uncovered racism in my own life—how I’ve participated in it, benefited from it, and perpetuated it—which I share below. May my examples inspire your reflection, awareness, and action.

MY INSTITUTIONAL RACISM

Institutional racism is discriminatory rules, policies, and practices within organizations or institutions.

I’ve supported businesses known to treat people of color in unfair ways because using their services was convenient for me.

I’ve encouraged ways of thinking and doing that reflect my culture. For example, I feel that a meeting has gone well if we’ve followed my linear-thinking agenda, avoided conflict, and produced certain kinds of outputs. I tend to devalue people who don’t excel in the skill sets I value and prefer to work with people who think and act like me. If the leadership of my organization shares my lens on what “being effective” or having a good meeting looks like, I’ll thrive while people from other cultural experiences, who may have their own methods and practices for effectiveness that are just as valid, will be at a disadvantage.

My Structural Racism

Structural racism is persistent racial injustice worked into and maintained by society.

Media and historical narratives that paint White people as dominant leaders and valuable assets have shaped my self-perception. I have assumed my presence and leadership is desired even in spaces where racially I am in the numerical minority. I’ve had to learn to be intentional about taking a support role.

Because, historically, people of my skin color have had economic opportunities unavailable to people of color, my family and I had the financial resources to buy a home—one in a predominantly Black neighborhood. While we moved with the intent to learn from and invest in our community, we also contributed to gentrification and its associated displacement.

My Implicit Biases

Implicit biases are unconscious personal biases and stereotypes.

White ideologies have shaped in me a pro-White view of how the world works. I grew up with the belief that people can succeed if they try. As a result, when I interact with people of color who are struggling, my initial reaction may be that they need to work harder, must be doing something wrong, or don’t have what it takes, rather than considering the impact of systemic racism.

After hearing a Black man talking about the ways he loves and cares well for his daughter, I found myself being especially encouraged. Upon further reflection, I realized that I wouldn’t have had the same response to a White man because I would’ve expected him to be a good father. Sadly, my encouragement came from an expectation that men of color are less likely to be involved fathers.

I spoke Spanish to a woman who appeared to be Hispanic/Latino, assuming it was her first language. Though this was my attempt to value her culture, she could’ve perceived it as reflecting a belief that people from her ethnic group don’t speak English, or must speak Spanish.

A Call to Self-Reflection

In acknowledging ways we’ve been perpetuating racism, we need not label ourselves as bad people. We need not declare we are “a racist,” in the sense that we often use that label—as a damning marker of our identity.

But we must admit that we can, and often do, perpetuate racism. We can have a racist impact, even without intent or awareness.

Acknowledging our potential for racist impacts is the first step in changing our thoughts and behavior. We can lead in our spheres of influence by first changing ourselves.

Exploring our racist tendencies isn’t an easy journey. But we can make real progress, one step at a time, empowered by God’s grace. I invite you to join me in self-reflection.

Reflection Questions

How do any of my life’s examples of institutional or structural racism resonate with your experiences?

As you discover any unjust attitudes or behaviors, how might you want to connect with God about it—in expressing lament or confession, in seeking wisdom, forgiveness, courage, or hope? What does the Gospel mean for you in this moment?

Do you notice attitudes or behaviors in your workplace, church, or other groups you participate in that contribute to racial disparity and division? With whom could you share your concerns?

Take Action

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge