BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

2016 WOVEN CONSULTATION [Photojournal]

Though drawn together for assorted reasons, the women who gathered shared a common commitment to Christ and a desire for wholeness. Whether they admitted to feeling overwhelmingly busy or being satisfied with their pace of life, all knew well the struggle of maintaining balance through life’s changing seasons.

WOVEN CONSULTATION

March 5th, 2016

By WOVEN

WOVEN CONSULTATION 2016

- A gathering of Christian women: leaders in the home, church, workplace, and community.

- A space to share stories, foster relationships, and develop strategies for overcoming obstacles.

- Dependent on prayer, permeated by fellowship, and yielding a practical response to equip churches to better support women.

SEEKING WHOLENESS

Though drawn together for assorted reasons, the women who gathered shared a common commitment to Christ and a desire for wholeness. Whether they admitted to feeling overwhelmingly busy or being satisfied with their pace of life, all knew well the struggle of maintaining balance through life’s changing seasons.

WELCOMING DIVERSITY

Beauty arose from their shared desire to grow as women of God as well as from their dynamic diversity. The Consultation welcomed 104 women from all generations, 59 occupations, 53 churches, and 45 Christian ministries throughout Greater Boston. Their racial diversity reflected the people of the city. Women who were differently abled were well served. The babies of young mothers joined in and children played nearby under watchful care.

“I like the fact that the leaders are helping to create safe spaces for women. I love the diversity!”

“Refreshing to be with women across denominational lines.”

“So nice to network with others outside my church walls.”

“I could see that people with varying abilities were welcomed and had a part to play.”

“Connecting with a diverse group of women is necessary to move forward towards all justice issues.”

HERE'S MY STORY

Five women shared stories from the front of the room that explored their pursuit of balance: What is it? What are the obstacles? What resources are there for realizing balance? How do we move ahead? As stories were told and hearts were opened, women found comfort in shared experiences, support in their journey, and inspiration to take the next step toward wholeness in Christ.

“I want to know more from women I wouldn’t typically gather with on a regular basis to expand my horizons. This is a big world and we serve a BIG GREAT God who is the master of it all. There is a reason why we are all here together. We need to stop isolating ourselves!”

“I loved that people were willing to share their lives and struggles and there was no judgement, only others willing to hold each other up.”

REFLECTION AND PRAYER

After each story, the women entered into quiet times of personal reflection, active table discussion, and interactive text polling. Women were moved to pray for each another, admonish each other, and offer loving support.

“Meeting other women in ministry who love the Lord was a highlight and it was helpful to draw out concerns I probably wouldn’t address otherwise.”

“Being a part of a larger community facing similar issues is very empowering.”

IMAGINING SOLUTIONS, DEVELOPING STRATEGIES

Moved to address the obstacles to balance and wholeness which they exposed and identified, the women worked together, shared resources, and collectively imagined how these obstacles could be overcome. Principles and guidelines gleaned from the wisdom and practical advice shared around each table will be passed on to churches in Greater Boston so they can better support Christian women in leadership.

EXPERIENCING GROWTH

At the day’s end, each woman left with something new, changed by what the Lord had done through this time in community. Some summarized their experience with words like “empowered” and “encouraged.” Hope came with many faces: renewed relationships, fresh strategies, and personal support in the seasons to come. The Consultation staff looks forward to supporting and equipping women leaders as they move forward in grace and see God’s work blossom and grow.

“The Woven Consultation helped to empower me in my walk with Christ even more and also in my calling. I further enjoyed the connections and relatable stories shared.”

“God really spoke to me, challenged me, provoked me and reassured me. I met new people.”

“I am going away more alive and empowered about living authentically before the Lord and others.”

The Woven Consultation is a project of the Applied Research and Consulting Department at Emmanuel Gospel Center.

The Story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston

About 30% of all Brazilians living in the U.S., approximately 68,197, reside in New England and Portuguese is the third most spoken language after English and Spanish in the region. What are the strengths and opportunities of the predominant Brazilian-speaking churches in New England today? Kaye Cook and Sharon Ketcham offer a quick update on the status of New England’s Brazilian churches, their history, strengths and challenges.

The Story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston

by Kaye V. Cook, Ph.D. and Sharon Ketcham, Ph.D.

an updated analysis based on work done previously by Pr. Cairo Marques and Pr. Josimar Salum in New England’s Book of Acts, Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007

Brazilians in New England

About 30% of all Brazilians living in the U.S. reside in New England (approximately 68,197 Brazilians according to the Boston Redevelopment Authority, 2012), and Portuguese is the third most spoken language after English and Spanish in New England (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Brazilian churches in the Boston area are strikingly dynamic, and there is significant turnover in pastors as well as attendees, often because individuals go back and forth to Brazil.

What are the strengths and opportunities of the predominant Brazilian-speaking churches in Greater Boston today? Before we answer that question, we need to consider the roots of Boston’s Brazilian church community.

History and Contemporary Context

The history of Brazilian churches in Boston is very much shaped by the context of Brazil. Historically, the dominant religion in Brazil is Catholicism, which was the religion of the Portuguese settlers (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). However, fewer people in Brazil today report being Catholic than in previous generations. Whereas more than 90% of Brazilians reported being Catholic as recently as 1970, 65% reported being Catholic in the 2010 census (PEW, 2013).*

The largest Pentecostal church group in Brazil is the Assemblies of God (Assembleias de Deus) with more than 23 million members (Johnson & Zurlo, 2016). Spiritualist religions, which emphasize reincarnation and communication with the spirits of the dead, are also common. More recently, Protestantism―especially Pentecostalism―has had a major impact with 22% reporting being Protestant as of 2010 (Pew, 2013). The earlier Protestant influence was a result of missionary work and church planting, but most of the major Protestant denominations now have an indigenous presence in the country (Freston, 1999) and today’s Brazilian Protestant church is strikingly indigenous.

Pentecostals in Brazil resist typology because of their rapid growth and diversity. The historical Pentecostals (primarily those growing out of missionary endeavors such as those by the Foursquare Church) emphasize the Holy Spirit, the Spirit’s manifestations in gifts, separation from the world, and a high behavioral code. NeoPentecostals such as participants in the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, a denomination which was established in 1977, continue to emphasize the Holy Spirit, especially healing and exorcism, and make connections between Christianity, success, and happiness. NeoPentecostals may also move away from a separatist worldview and strict behavioral standards and toward increased cultural integration, and some emphasize prosperity rather than a central focus on Christ and the Bible (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). The movement toward greater cultural integration has opened doors for political activity (Freston, 1999). There is debate however about whether NeoPentecostalism can be reliably distinguished from Pentecostalism (Gedeon Alencar, personal communication, 3 October 2015). Some also suggest that PostPentecostalism is the preferred term for those who operate in a way that is similar to a business, emphasize cultural integration, and bypass the traditional elements of Pentecostalism such as the “central focus on Christ and the Bible,” focusing instead on a prosperity gospel (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012, p. 159).

Pentecostals (including NeoPentecostals) comprise 85% of the Protestants in Brazil (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012). Five years following the 1906-1909 Azusa Street revivals, the rapid expansion of Pentecostalism reached Brazil through Swedish Baptist missionaries (Chesnut, 1997). Due to urbanization and the growth of the mass media (Freston, 1999), there was simultaneous growth among Pentecostals in the North (Belem) and Southeast (São Paulo) regions. Much of the recent growth in Brazil is accounted for by six denominations, three of which are of Brazilian origin: Brazil for Christ, God Is Love, and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (Freston, 1999).** The most rapid recent growth in Brazil among Pentecostals is due to growth in the Foursquare (or Quadrangular) Church, Brazil for Christ, and God Is Love (Juergensmeyer & Roof, 2012).

According to the IBGE Census, in 2010 there were almost 4 million Baptists in Brazil represented by the Brazilian Baptist Convention (affiliated with the U.S. Southern Baptist Convention) and the National Baptist Convention (Renewalist Baptists). In addition, Reformed churches were common such as the Presbyterian Church of Brazil, the Independent Presbyterian Church, and the Renewed Presbyterian Church. Adventists, Lutherans, and Wesleyans were also represented.

Baptists

According to Marques and Salum (2007), Pastor Joel Ferreira was the first Brazilian Minister to start a Portuguese-speaking church in New England. No interviewee knew of an earlier presence. Pastor Ferreira was a member of the National Baptist Church in Brazil and planted a Renewed Baptist Church in Fall River in the early 1980s that grew to about 500 members (Marques & Salum, 2007), also called the LusoAmerican Pentecostal Church. Pastor Joel returned to Brazil in 1991 and later returned to the U.S. where he recently died. Today there are several (perhaps 6-9) churches in Massachusetts that were born from this pioneer church.

Several renewal Baptist church groups exist in New England, including the Shalom Baptist International Community in Somerville led by Pr. Jay Moura and the Igreja Communidade Deus Vivo led by Pr. Aloisio Silva.

American Baptist Churches began a new church-planting movement in Boston in 1991 and planted primarily renewal churches (Marques & Salum, 2007). This movement gained force from 2001 to 2004 when about 20 new Brazilian Portuguese churches were planted in Massachusetts and Rhode Island under the New Church Planting Coordination led by Rev. Lilliana DaValle and Pr. Josimar Salum. This forward movement stalled due to issues of church doctrine. Another group of churches that were established with Baptist connections are the Vida Nova churches including Igreja Batista Vida Nova in Medford (Pr. Jose Faria Costa Jr) and Igreja Batista Vida Nova (Pr. Alexandre Silva).

The Southern Baptists also planted many churches since 1995. There are about 30 of these churches in New England, including the Portuguese Baptist Church in Inman Square, Cambridge (Pr. Silvio Santos), the Celebration Church in Saugus (which was in Malden and Charleston under the direction of church planter Pr. Joe Souza), and the First Brazilian Baptist Church of Greater Boston (also known as the Lovely Church) with Pr. Antonio Marques Ferreira.

Assemblies of God

The first Assembly of God churches in Boston were established by Ouriel de Jesus. He was invited by Pr. Alvacir Marcondes to Somerville in 1985, and under his supervision the Assemblies of God denomination in the U.S. experienced tremendous growth. After September of 2001, Pastor de Jesus said he received a message from God to lead a great revival and began holding revival meetings all over the country and world. Currently, he is the pastor of the World Revival Church in Everett, which now has over 70 congregations throughout the U.S. and in 17 other countries with a membership exceeding 15,000.

Despite Pr. Ouriel’s success at leading revivals and church growth movements, his ministry has been accompanied by a great deal of controversy. As a result, in 2002, the church was expelled from the Assemblies of God denomination in both the U.S. and Brazil. The mother church and those he planted are no longer allowed to call themselves Assemblies of God and instead have taken the name The World Revival Church, later adding “Boston Ministries” (Pinto-Maura & Johnson, 2008). These churches continue to exist under Ouriel’s leadership.

There are 36 Brazilian Assemblies of God churches in Massachusetts, including Igreja Vida Assemblies of God (Pr. Salmon Silva) and Mission Assembly of God (Pr. Joel Assis).

Presbyterians

Several Presbyterian churches are in the Boston area. Christ the King church in Cambridge was established in the early 1980s by Pr. Osni Ferreira, who had a multicultural vision. Several additional Brazilian Presbyterian churches have been planted by this church, including New Life Presbyterian (Framingham), Bethel (Marlboro), and Christ the King (East Boston).

Church of Christ

In 1984, the Church of Christ established the Hisportic Christian Mission (HCM) in East Providence, Rhode Island, led by Rev. Wayne Long with the vision to reach Portuguese-speaking people in New England (Hisportic stands for Portuguese as Hispanic stands for Spanish). In 1990/1991 Rev. Aristones Freitas and Josimar Salum planted the first Brazilian Church in Worcester, Mass. Today there are about 46 churches that have been established through the HCM, of which 26 are in Mass., an additional 10 are in other New England states, and three are in Brazil.

Independent churches. The Foursquare Gospel Church arrived in 1991 and now has several churches throughout New England. These include the Communidade Brazileiro of Framingham, PenteBaptist (Pr. Dimitri Grant) and Malden Portuguese Foursquare Church (Pr. Cairo Marques).

Strengths and Opportunities for the Brazilian Churches in Boston and New England

Strengths

The strengths of the Brazilian churches are many. Some churches have numerous young people, many pastors are committed to preaching the Gospel, and large numbers of lay people who fill these churches take seriously their responsibility to know the Bible and to serve Christ. Brazilians as a group are well-accepted in the community. We heard stories which indicate that this is not always true for individuals, particularly with regard to immigration, but we also saw newspaper articles extolling the benefits that Brazilian churches have brought to the community! Brazilian churches can and often do reach out to contribute to their larger communities.

Nevertheless, there are many challenges, including the language barrier, how immigrants can participate in the larger culture and retain their Brazilian culture, immigration issues, and high levels of turnover among church attendees, in part because of immigration. In a series of interviews conducted in 2015, virtually everyone mentioned the challenge of finding affordable meeting space. Many churches do not have their own buildings, and, if they do, they struggle to maintain them. Renting space is increasingly expensive, and there are often problems parking near urban churches. Difficulties surrounding meeting together, an essential aspect of being a church, results in significant stress in the community.

These churches have other struggles as well. Converting new people to Christ is often hard. There is a need to raise up new pastors, because many pastors have been in the U.S. for several decades. It can be difficult to recruit young people to such a challenging ministry and one focused specifically on the Brazilian community.

Some challenges come from outside the churches and others from within. Networking among Brazilian pastors is challenging even though there are some groups that meet regularly, including BMNET (Brazilian Ministers Network), Brazilian Prayer Network of Boston, and Pastors Fraternal Union in Fall River. When asked during an interview to name the single thing that would be most helpful to them, pastors frequently said that they would like better contact with other Brazilian pastors. Nevertheless, multiple factors can limit opportunities for networking:

- Journeyman pastors work a full-time job in addition to pastoring and lack time for networking.

- Instability in church membership as members return to Brazil contributes to pastor overload and burnout.

- Pastors may compete among themselves for church members.

- The needs of first, second, and third generation immigrants are difficult to navigate. For example, churches struggle with whether to have services in English or maintain evening services as in Brazil versus the American way of holding morning services.

Opportunities

The opportunities for growth and change are many. Among them are these:

The Brazilian population in Massachusetts is estimated by the 2005 census to be approximately 84,000 individuals, many of whom are not in church. There is great potential for church growth within (and outside) the Brazilian population.

Brazilian churches can get more involved with the local and global realities, e.g., by supporting other church efforts such as limiting human trafficking.

They can perhaps better educate their members about the problems with the prosperity gospel, and the financial abuses that are too often perpetrated against church members (including the Ponzi scheme called Telex Free in which some pastors participated).

They need to strategize for the future, as more and more of their members speak English and either ask for changes in Brazilian churches, or leave for English-speaking churches.

The Brazilian churches have much to teach the larger community. Church planting appears to be a primary focus for Brazilian Christians and virtually every church visited had either already engaged in church planting or hoped to at some point. Many churches also feel called to send out missionaries. Even though we were unable to get an estimate of the number of missionaries commissioned, anecdotal evidence suggests that there are surprisingly many missionaries from these churches. And finally, at least one of these churches feels called to minister not just in their local community but around the world. In a church community that was itself not financially flush, the church has supported orphanages in Brazil and dug a much needed well in a needy community without a church, while also supporting ministries in Africa. This level of commitment is remarkable and challenging to mainstream American churches.

In conclusion, the size, energy, number of young people, and commitment to church growth in Brazilian churches should inspire the Global Church. The needs are great, and the opportunities are many for serving those engaged in these impressive churches and for ministering together in the larger community.

Endnotes

*Johnson and Zurlo (2016) report approximately 76% Catholics and 28% Protestant. These numbers refer to the percentage of all Brazilians and demonstrate that some Brazilians claim dual affiliation or membership in more than one community of believers. By their estimate, the number of dually affiliated believers is 13% of Brazilians, many of whom claim to be both Protestant and Catholic. Their estimate is based on an effort to provide a more precise estimate than the 2010 census, in part by collecting information from additional sources than the census and in part by allowing individuals to report belonging to more than one religion.

**The remaining three churches are the Assemblies of God, the Four-Square Church, and the Christian Congregation (Freston, 1999).

References

Boston Redevelopment Authority. (2012). New Bostonians 2012. BRA Research Division Analysis.

Chesnut, R. A. (1997). Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom in Brazil: The Pentecostal Book and the Pathogens of Poverty. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Freston, Pl. (Jan-Mar, 1999). “Neo-Pentecostalism in Brazil: Problems of Definition and the Struggle for Hegemony.” Archives de sciences sociales des religions. 44E, No 105, p. 145-162.

IBGE (Institute Brazileiro de Geografia e Estatistica) (2010). Census. http://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/en/ censo-2010 Accessed 6.27.2015.

Johnson, T. M., & Zurlo, G. A. (Eds.) (2016) World Christian Database. Leiden/Boston: Brill. Accessed at worldchristiandatabase.org/wcd on 1 January 2016.

Juergensmeyer, M., & Roof, W. C. (Eds.) (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Marques, C., & Salum, J. (2007). The Church among Brazilians in New England. In R. Mitchell & B. Corcoran (Eds.), New England’s Book of Acts. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Pew Research Center (2013). Brazil’s Changing Religious Landscape. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/07/18/brazils-changing-religious-landscape/ Accessed 6.28.2015.

Pinto-Maura, R., & Johnson, R. (2008). Abused God. Maitland FL: Xulon Press.

U.S. Census (2009). ActivitiesUpdate_June09. Accessed on 8.2.2015 from http:// www.henrietta.org/index.php/doccenter/2010-us-census-documents/6-june-2009-census-2010-activities-update/file

This essay updates the story of the Brazilian Church in Greater Boston as told in New England’s Book of Acts (2007), originally published by the Emmanuel Gospel Center in preparation for the October 2007 Intercultural Leadership Consultation. The earlier version was written by Cairo Marques and Josimar Salum, and work on the current document began by talking with them as well as 45 other Brazilian pastors and lay people in the Greater Boston community. Their observations are integrated into the comments above. —Kaye Cook and Sharon Ketcham, February 24, 2016.

__________

See the original 2007 article on the origins of the Brazilian church movement in New England in New England’s Book of Acts.

Boston Youth Workers' Training Wish List

Boston Youth Workers' Training Wish List

Data Source: Boston Urban Leadership Initiative Survey, 2017. 50 Respondents, percentages of "Yes" or "Might Be" responses to "Please tell us what kinds of training you'd find helpful."

Data Source: Boston Urban Leadership Initiative Survey, 2017. 50 Respondents

Data Source: Boston Urban Leadership Initiative Survey, 2017. 50 Respondents

Data Source: Boston Urban Leadership Initiative Survey, 2017. 49 Respondents.

Data Source: Boston Urban Leadership Initiative Survey, 2017. 50 Respondents

OTHER TOPICS REQUESTED

1. BROADER Community Collaboration

- Networking

- Building connections with what churches and other ministries are already doing

- Church without walls - urban community ministry

- Connecting with other youth workers and learn from each others' successes and challenges

- Relating to neighborhood/community groups that spend time with young people

- Strategies for collaborating with fellow youth workers and organizations

- Mentors, Big Brothers who connect with youth

- Connecting families and youth together

- Collaborating with government and/or community organizations

2. Youth Worker Peer Fellowship

- Building connections with what churches and other ministries are already doing

- Connecting with other youth workers and learning from each other’s successes and challenges

- Strategies for collaborating with fellow youth workers and organizations

- Prayer for youth and youth ministers

3. Trauma Response & Youth in Crisis

- training in traumatized youth and their families

- grief

- homeless youth

- school dropouts

- navigating through tween and teenage years

4. Youth Engagement

- High school student behavior management strategies, tools, and best practices.

- Teaching to a variety of learners in one classroom; how to keep them all engaged; classroom management.

- Keeping youth motivated.

5. Special Topics

- Creating healthy boundaries with social media and technology and learning to discern the value and intent of information posted online.

- Training in ADHD and autism.

- Understanding the LGBT community.

- Apologetics and how current day religions (Black Hebrew Israelites, Mormonism, Islam) attack the Gospel and how to help youth stand firm.

- How finances can help or hinder serving and helping underserved youth.

- How to manage and organize your time and your workload to have a stress-free and smooth work life!

The Unsolved Leadership Challenge

Our research on new church development in Greater Boston yielded general information with a special focus on women in leadership. The hope is that this study can become a source of “mainstreaming” gender parity discourse within the church, as part of an overall discussion of the practical needs of church planters in the areas of leadership and ministry development.

The Unsolved Leadership Challenge

AIM OF THIS STUDY

In this study of new church development in Greater Boston, we identified at least 95 new congregations which have started in the last seven years. Forty-six were within the city limits of Boston. We completed 41 in-depth interviews with church planters who represented several different denominations, ethnic groups, and networks. The research yielded general information about the church planters and the new churches, with a special focus on women in leadership. The hope is that this study can become a source of “mainstreaming” gender parity discourse within the church, as part of an overall discussion of the practical needs of church planters in the areas of leadership and ministry development

A Report on the 2014 Woven Consultation Day for Christian Women Leaders

Christian churches believe that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender, are created in the image of God. Yet, often the Church falls short of honoring that image. Anecdotal and statistical evidence shows that women face disproportionate levels of violence, discrimination and challenge at least as much in churches as out.

Why a Consultation Day

Christian churches believe that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity or gender, are created in the image of God. Yet, often the Church falls short of honoring that image. Anecdotal and statistical evidence shows that women face disproportionate levels of violence, discrimination and challenge at least as much in churches as out.

Churches: Community Development is the New Community Service

Churches often excel at community service. But what might it look like for a church to build the capacity of a community? A reflection on a model of church work in community development.

Churches: Community Development is the New Community Service

By Bethany Slack, MPH, ARC Associate in Public Health & Wellness

Churches can have whole-health impacts in their communities. But churches who want to engage the physical needs of a local area need intention, planning, and a fuller picture of Christian love.

At the 2018 GO Conference in February, I attended a workshop called, “Bringing Life to Your Community, “ led by Archbishop Timothy Paul, President of the Council of Churches of Western Massachusetts (CCWM). There he presented a practical vision for engaging the whole-bodied needs of a local area.

The Archbishop reminded us of the insight (often attributed to Teddy Roosevelt), “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” Members of a community sometimes don’t know how much churches care until they see us helping to address pressing physical needs.

CCWM fleshes out Jesus’ “do unto others” call into thoughtful ways that churches can discover community needs and develop sustainable programs. The main insight I took away from the workshop was the difference between community service and community development.

Community SERVICE vs. Community DEVELOPMENT

When I was growing up, my church took serving the community very seriously. Our small groups and youth groups regularly volunteered at the church’s food pantry or community clothing distribution center. Our hometown of Harrisonburg, VA, was a prime destination for immigration, so our church helped sponsor refugees and immigrants for resettlement in the US.

Our church also maintained a fund for helping out with community needs. My dad administered the fund for many years, instilling in me a value of thinking beyond the needs of our own family. In my adult life, I’ve volunteered at free clinics and resource centers for the homeless. So community outreach is rooted deep within me.

But I would call my outreach experience “community service.” The Archbishop presented a model for something quite different—community development.

As a public health professional at EGC, I’m developing a Boston-based program to help Christian leaders and healthcare professionals across the city convene to address end-of-life care needs. But I’ve not been involved in community development work connected to a particular church body.

Community development involves going out into the community and doing a needs assessment, discovering with local partners:

What are the needs and opportunities of this community?

With whom can we partner?

What is the role of our church in the community?

What is our responsibility to the community?

How can we help build the community around us?

With the projects CCWM has developed from this discovery process, they’re not just giving out food or other items, but they’re trying to build the community’s own capacities. For example, CCWM is involved in mentoring youth, providing counseling, and other activities that help people get back on their feet or overcome their past.

Fullness of Life, Fullness of Ministry

CCWM’s approach is inspired by John 10:10, “The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy; I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full.” (NIV). For CCWM, “life to the full” includes five pillars of community health: spiritual, educational, economic, health, and social.

According to their “Vision 10:10” strategy, each of these five areas is an opportunity for the church to strengthen its surrounding community. Some of the ways CCWM has invested in these pillars in Springfield neighborhoods include:

opening a hotel to create jobs and revenue (economic)

obtaining a grant to mentor youth with incarcerated parents (social)

providing counseling for gambling and opiate addiction (health, social)

CCWM developed each of their initiatives in response to needs they observed in the community. For example, their interest in treating gambling addiction stems from the arrival of a new casino in Springfield.

My Next Steps

I’d like to see my current church come together to begin conversation about our role in the local community. That kind of shared discovery is not something I’ve seen. Mostly I’ve seen programs develop from the top down from the leadership, or even from the leadership practices of the churches that planted them.

We’re in Belmont, MA, and my husband and I have been a part of the church there since it was planted. As far as I know we haven’t yet held conversation about what it means to be in Belmont or our role in the Belmont community. We’ll need to also have some theological discussion around what it can mean (and doesn’t mean) to “be the church” beyond our walls.

My first step is to get together with one of the elders of the church and say, “Here are my thoughts about our serving the community. What do you think?”

We already have community outreach activities, and I don’t know how they came about. There may be these kinds of discussions going on behind the scenes that I don’t know about. Those of us not on the planting team haven’t yet had much influence on the kinds of community work the church does. So my first step is to connect with my church leadership.

I think God is inviting me to be open to what community development might look like to my church leaders. I’m not in leadership at the church. Yes, community development is on my heart, but I want to hear what’s in the hearts of the leaders too. Anything we do as a church, I’d want it to be coming not from me, but from the church as a whole.

For Reflection

Many of us attend churches outside of our home neighborhood or city. How does this reality affect our potential for community impact, individually and corporately, for the positive or negative?

Most of us attend churches that meet in a fixed location, whether owned or rented. How do we view our “place” in the neighborhood? Is it merely a space to gather, or is there potential or even responsibility to play an active role in seeking the good of the community?

Bethany Slack, MPH, MT, is the Public Health and Wellness research associate at EGC. Her passion is to see Jesus’ love translated into improved health and health justice for all, across the lifespan and across the globe.

Emmanuel Research Review

The Emmanuel Research Review (2004-2014) was a digital journal from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s Applied Research department that featured articles, papers, resources, and information designed to be a resource for urban pastors, leaders and community members in their efforts to serve their communities effectively. Ninety-five issues of The Review were published during its ten-year run from 2004 to 2014. On this page we offer a list of all issues published, and links to those that have been reposted to this new site.

WHAT IS IT?

The Emmanuel Research Review (2004 - 2014) was a digital journal from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s Applied Research department. The Review featured regular articles, papers, and other resources to support urban pastors, leaders and community members in their efforts to serve their communities effectively. Ninety-five issues of The Review were published during its ten-year run from 2004 to 2014.

THEN AND NOW

When EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting department began a comprehensive reorganization in 2014, we discontinued publication until we were in a better position to produce new materials that would be even more effective. In 2016, when we launched a new website, the ERR archive was no longer available. Now we are working to repost some of the best from the past while we continue producing new resources addressing a wide range of urban issues.

LIST OF PUBLISHED ISSUES

2014

Issue No. 95 — March 2014 — Knowing Your Neighborhood: An Update of Boston’s South End Churches. (EGC reassessed the status of churches in our own neighborhood, Boston’s South End.)

Issue No. 94 — December 2013 - January 2014 — Understanding Boston’s Quiet Revival. (Steve Daman, Senior Writer, EGC, offers questions and discussion that lead toward a working definition and overview of “the Quiet Revival.”)

2013

Issue No. 93 — October-November 2013 — Mapping A Systemic Understanding of Homelessness for Effective Church Engagement. (EGC’s Starlight Ministries shares a homelessness system map for Boston and suggestions as to how churches can more effectively engage and impact homelessness in their communities.)

Issue No. 92 — September 2013 — “Why Cities Matter” and “Reaching for the New Jerusalem,” Books by Boston Area Authors. (Reviews of: Why Cities Matter: To God, the Culture, and the Church, by Stephen T. Um & Justin Buzzard, and Reaching for the New Jerusalem: A Biblical and Theological Framework for the City, edited by Seong Hyun Park, Aída Besançon Spencer, & William David Spencer.)

Issue No. 91 — July-August 2013 — Grove Hall Neighborhood Study. (Story and statistics on many facets of life in one Boston neighborhood.)

Issue No. 90 — June 2013 — Hidden Treasures of the Kingdom Uncovered. Celebrating Ministries to the Nations: A Manual for Organizing and Planning an Event in Your City. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries, EGC, and Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director of Intercultural Ministries, describe a ministry event and the journey they pursued to pull it together.)

Issue No. 89 — May 2013 — 2013 Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (Excerpts from the award paper, “Cambridge City-Wide Church Collaborative Cooperates to Meet Community Needs,” by Megan Footit, and abstracts from the three runners-up.)

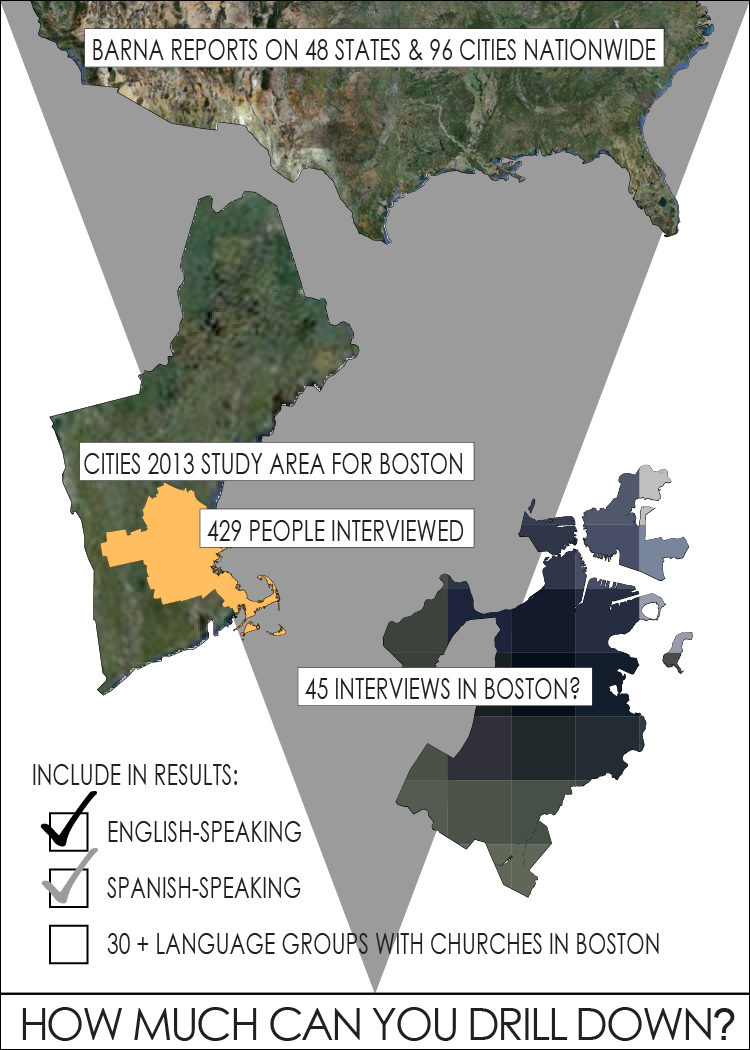

Issue No. 88 — April 2013 — Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical? (Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, EGC, evaluates the sources, accuracy, limitations, and weakness of some commonly used church statistics, especially with regard to their application in Boston.)

Issue No. 87 — March 2013 — Christian Engagement with Muslims in the United States. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, hosts a video conversation on Christian Engagement with Muslims in the U.S. Panelists: Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian–Muslim Relations, EGC; Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.)

Issue No. 86 — February 2013 — The Vital Signs of a Living System Ministry. (Dr. Douglas A. Hall, President of EGC and author of The Cat and the Toaster: Living System Ministry in a Technological Age, shares how Living System Ministry principles serve as vital signs which can guide our understanding and practice of leadership in urban ministry.)

2012

Issue No. 85 — December 2012–January 2013 — “Toward A More Adequate Mission Speak” and Other Resources by Ralph Kee. (An introduction to five booklets by Boston-based church planter and animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, Rev. Ralph Kee.)

Issue No. 84 — November 2012 — The Boston Education Collaborative’s Partnership with Boston Public Schools. (History and highlights of recent collaboration between EGC’s Boston Education Collaborative and the Boston Public Schools Faith-Based Partnerships in building church-school partnerships; and details on the BEC’s “Reflection and Learning Sessions” that provide support for Christian leaders working with students.)

Issue No. 83 — October 2012 — Churches in Boston’s Neighborhood of Mattapan. (Erik Nordbye, Research Associate of EGC, studied and analyzed data on 65 Christian churches in Boston’s diverse Mattapan neighborhood.)

Issue No. 82 — September 2012 — Christian Churches in Somerville, Mass. (A profile of 46 Christian churches in the city of Somerville, Mass.)

Issue No. 81 — August 2012 — Christian Churches in North Dorchester of Boston, Mass. (Hanno van der Bijl, Research Associate at EGC, studied the diverse and vital expressions of the church in the North Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. The report also documents the slow growth in the number of churches over the last 25 years.)

Issue No. 80 — July 2012 — Developing Safe Environments for Learning and Transformation. (Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries, EGC, shares from his experience regarding “a model for personal and organizational transformation” while underscoring the importance of creating a safe environment.)

Issue No. 79 — June 2012 — Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (The 2012 award paper, “Miriam’s House Ministries and The Melville Park Micro-enterprise Experiment,” by Jim Hartman, is presented in its entirety, and there are links to the executive summaries of the three runners up.)

Issue No. 78 — May 2012 — The Rise of the Global South: The Decline of Western Christendom and the Rise of Majority World Christianity, by Elijah J. F. Kim. (An introduction to the above named book by Elijah J. F. Kim, former Director of the Vitality Project, EGC. Dr. Kim says “the center of gravity of the Christian faith has shifted from the West to the non-West.”)

Issue No. 77 — April 2012 — The Black Church and Hip Hop Culture & Under One Steeple, Books by Boston Area Authors. (Reviews of The Black Church and Hip Hop Culture: Toward Bridging the Generational Divide, edited by Emmett G. Price III, and Under One Steeple: Multiple Congregations Sharing More Than Just Space, by Lorraine Cleaves Anderson, former pastoral of International Community Church in Allston.)

Issue No. 76 — March 2012 — Hartford Survey Project: Understanding Service Needs and Opportunities. (Jessica Sanderson of Urban Alliance shares about the purpose, process, analysis, findings and application of the Hartford Survey.)

Issue No. 75 — February 2012 — Behind the Scenes: Setting the Stage for Conversation about the Church in New England. (Video series from Brandt Gillespie of PrayTV and Dr. Roberto Miranda of Congregación León de Judá in Boston about the church in New England.)

Issue No. 74 — January 2012 — Shared Worship Space, an Urban Challenge and a Kingdom Opportunity. (Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC, outlines the challenges of churches sharing space.)

2011

Issue No. 73 — December 2011 — Let’s Do It! Multiplying Churches in Boston Now. (Rev. Ralph A. Kee, animator of the Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, connects first century practices with 21st century potentialities for Boston.)

Issue No. 72 — November 2011 — Crossing Beyond the Organization Threshold. (Dr. Douglas A. Hall, President, EGC, shares thoughts on the limitations of organization and the danger of having it become our ministry’s focus, and how we can use organization and technology appropriately to benefit a living system.)

Issue No. 71 — October 2011 — Human Trafficking: The Abolitionist Network. (Sarah Durfey, director, the Abolitionist Network, an emerging ministry of EGC, talks about how we can address human trafficking using a Living System Ministry approach.)

Issue No. 70 — September 2011 — Urban Ministry Training in Metro Boston. (Hanno van der Bijl, Research Associate, EGC, offers a brief introduction on urban ministry training in Metro Boston, the Urban Ministry Training Directory, a brief analysis, and a list of related resources.)

Issue No. 69 — August 2011 — The Diverse Leadership Project. (Dr. Bianca Duemling, Assistant Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC, gives a brief overview of the project which seeks to better understand leadership development, styles, and priorities within various ethnic church communities. Includes interviews with six New England church leaders in five different ethnic contexts.)

Issue No. 68 — July 2011 — Metro Boston Collegiate Ministry Project: Focus Group/Learning Team Report. (The story of how the collaborative project began, initial group assumptions, and the “hexagonning” exercise that engaged 50 local leaders in a shared learning process to understand local college ministry.)

Issue No. 67 — June 2011 — Metro Boston Collegiate Ministry Project: Student Enrollment Report. (Who attends Boston’s colleges? This report examines student enrollment profiles for each of the 35 schools in Metro Boston.)

Issue No. 66 — May 2011 — Emmanuel Applied Research Award: Student Recipients. (The 2011 award paper, “Faith-Based Healthcare for the Underserved of Lawrence, MA: A Pilot Project,” by Stephen Ko, is presented in its entirety.)

Issue No. 65 — April 2011 — Boston Education Collaborative Church Survey Report. (How Boston-area churches are engaged in education, what areas of programming they are interested in further developing, and what resources are needed for them to become more involved in education.)

Issue No. 64 — March 2011 — Connecting the Disconnected: A Survey of Youth and Young Adults in Grove Hall. (An April, 2010, report on out-of-work and out-of-school young adults ages 16-24 in the Grove Hall area of Boston, and an interview with Ra’Shaun Nalls and Martin Booth of Project R.I.G.H.T., who share the story behind the study.)

Issue No. 63 — February 2011 — Youth Violence Systems Project Special Edition Review. (An overview of the community-based process that is at the heart of the Youth Violence Systems Project (YVSP), the YVSP strategy lab, the reason why we haven’t solved the gang violence problem, and what we are learning.)

Issue No. 62 — January 2011 — The Urban Apostolic Task. (In this issue, Rev. Ralph Kee, animator, Greater Boston Church Planting Collaborative, illuminates the vision, practical instruction, and urgency of an apostolic ministry that engages the entire church in “new-world building movements.”)

2010

Issue No. 59 — September/October 2010 — A New Kind of Learning: Contextualized Theological Education Models. (Dr. Alvin Padilla, Dean of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Center for Urban Ministerial Education, Boston, considers the challenge theological schools have best serving the needs of diverse cultures in cities today.)

2008

Issue No. 41 — September/October 2008 — Urban Youth Mentoring. (Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, summarizes his research findings regarding various practical aspects on mentoring youth in an urban context. Rudy’s research draws from both secular and faith-based sources regarding preparation, planning, recruiting, screening, training, matching, support, monitoring, closure, and evaluation of youth mentoring programs.)

More to come!

This is just a start. Stay tuned for more back issues listed and posted on this site. Or check out the Wayback Machine link below for another way to find back issues.

Learn More / Take Action

Questions? Is there something missing from our archives that you need? If you have questions or comments about the Emmanuel Research Review, don’t hesitate to be in touch. We would love to hear from you!

Researchers may find additional back issues by searching the internet “Wayback Machine” here:

The City Gives Birth to a Seminary

Based on an interview with Rev. Eldin Villafañe, Ph.D., the founding director of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), this article tells the story of Dr. Villafañe’s calling to launch CUME in 1976 and how the school rapidly took shape. Dr. Villafañe recalls the fruitful synergy at work among three primary players: CUME, the Emmanuel Gospel Center, and a network of new churches emerging from the Quiet Revival.

The City Gives Birth to a Seminary

The founding of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston campus, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education.

by Steve Daman, Senior Production Advisor, Applied Research and Consulting, EGC

What if you want to start a seminary? Where do you begin?

What if, instead of showing up with long-term goals and administrative strategies for organizational development, you

choose to allow the color and complexity and diversity of a changing city to shape the seminary?

start by listening rather than directing?

not only welcome collaboration, you insist on it?

launch your first class just three months after you get the nod to start?

What would that look like? It would look like CUME, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston campus.

Eldin Villafañe

In the fall of 1973, Eldin Villafañe and his wife, Margie, settled into student housing at Boston University (BU) and Eldin started work on a Ph.D. in social ethics. Already a graduate of Central Bible College and Wheaton Graduate School of Theology, Eldin had been serving as director of Christian education for the largest Hispanic Assemblies of God church in the country at the time, Iglesia Cristiana Juan 3:16 in the Bronx. His thought was to come to BU, get the degree, and get back to New York. But God had another plan.

Not long after coming to Boston, Eldin made his way to a little bookstore on Shawmut Avenue, a store bursting with books and music in both Spanish and English, furnished with vintage display counters and decorated with brightly painted maracas, guiros, tambourines and a variety of flags. The little store seemed dark at first coming off the street, yet the room was always full of cheerful conversation, lively music, and warm Christian fellowship.

Eldin struck up a friendship with the manager, Web Brower, who had launched the store in 1970 as a ministry of the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC). The store served as a resource center for the growing Hispanic church community as thousands of Latinos were moving into Boston from across Latin America as well as from New York and Puerto Rico.

One day, Web invited Eldin to join the planning team for an inner-city Christian education conference. It was a good fit as Eldin was a seasoned Christian education director and well-respected in his denomination, the Assemblies of God. Eldin remembers, “They asked me to mobilize some Latinos. And Web and the folks were thinking, you know, if we get 20 or 30 people that would be great. Well, because I had been known in my denomination and I knew the pastors, I was able to bring close to 300 Latinos.”

The conference spilled over into two churches. That event built new relational bridges for Eldin, especially with some of the city’s African American leaders such as Michael Haynes, Bruce Wall, and VaCountess (V.C.) Johnson, all on staff with Twelfth Baptist Church at that time. God gave him much grace, he says, and the other leaders valued his contribution to this conference.

Somewhere along the way, Eldin was asked to be a guest lecturer for a few seminary classes held at the Emmanuel Gospel Center. In 1973, the same year that the Villafañes came to Boston, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (GCTS) launched a program called the Urban Middler Year (UMY). Seminarians could choose to spend their second full year of study in Boston, attending classes at the Gospel Center taught by Doug Hall, at that time the director of EGC, and Professor Steve Mott of Gordon-Conwell, with additional help from Professor Dean Borgman and other urban leaders. Students would serve with an inner-city church and be mentored in urban ministry. Then they would return to Gordon-Conwell Seminary in Hamilton for their third and final year. When Eldin spoke at the Gospel Center those few times, he did not realize he would soon be working in partnership with Steve Mott.

The Birth of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME)

In 1969, one of the mandates of the newly formed Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, arising from the merger of the Conwell School of Theology in Philadelphia and the Gordon Divinity School in Wenham, Massachusetts, was to engage the city in some fashion. Both schools had historical commitments to urban ministry that it was unwilling to abandon; however, the specific shape and form for the new institution remained rather unclear.

Initially, Dr. Stephen Mott was hired to direct a program to be housed in Philadelphia, continuing the Conwell tradition of training African American clergy. In effect, Dr. Mott became a full-time professor of church and society, located at the Hamilton campus of Gordon-Conwell in South Hamilton, Massachusetts.

Other GCTS constituencies, particularly urban clergy, also shared this interest that the seminary’s original urban mandate become a full reality. Dr. Michael Haynes, senior Pastor of the historic Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and a longtime trustee of GCTS, took a leading and crucial role at this juncture. He became a strong advocate for the Seminary’s need to be involved in the inner city, and powerfully articulated the plight of the church in the inner city to the Seminary’s Trustees and senior administration.

Before Gordon-Conwell launched the Urban Middler Year program, there had been talk of doing more for the city. A few years earlier, in 1969, Doug Hall sent a letter to the seminary’s leadership asking them to consider addressing three critical needs that Doug and his team saw emerging in Boston:

the need for an urban training component for traditional seminary students, which initially was addressed in 1973 with the start of UMY

the need for research on demographics and trends in the city to keep ministerial training relevant and to inform the pastors

the need for contextualized ministerial training for pastors already working in Boston.

The UMY program was importing eager seminarians into the city. Gordon-Conwell never addressed the research concern, but, in 1976, God sent a researcher to EGC. Rudy Mitchell, still EGC’s senior researcher, has been studying the city and its churches for four decades.

But what was to be done about the remaining challenge, the need to better equip pastors already serving? Many pastors in Boston’s newest churches had little or no formal education, many did not speak English, but, with anointing from God, they were leading dozens of Boston’s most effective churches.

Doug Hall remembers conversations with busy, bi-vocational pastors who wanted more training, but wondered how to fit that into their busy lives, as they were already feeling burned out. He also heard his friend Michael Haynes voice deep concerns about the lack of access to evangelical ministry training and higher education for urban residents—a gap that had widened in the twenty years since Gordon Divinity School had moved out of the city of Boston in the mid-1950s.

By 1976, the leadership at Gordon-Conwell was ready to do more. They began looking for the right person to build bridges among urban church leaders across many ethnic groups, someone who could administer new programs—possibly an urban seminary, and teach and mentor students. Professor Steve Mott asked Eldin if he was interested, and then Doug Hall and his wife Judy drove Eldin the thirty miles up Route 1 to introduce him to the seminary leaders.

When the offer was extended, Eldin readily agreed to join Gordon-Conwell as assistant professor of church and society, working alongside Steve. Eldin was made coordinator for the Urban Middler Year program and he was asked to do one more thing: to begin to think about ways the seminary could establish a new and separate program for training and equipping the urban pastors already serving congregations.

“There was great interest in doing this, and I just took the ball and ran,” Eldin says. V.C. Johnson, a Gordon-Conwell graduate and ordained minister who was working at Twelfth Baptist, was also already involved in exploring this idea. V.C. and Professor Dean Borgman had been conducting some simple surveys to see whether a program for indigenous pastors and leaders would fly.

Eldin and V.C. soon began working together. Eldin recalls, “I had been named the director of the project, and I started calling V.C. the assistant director right away rather than a secretary or administrative assistant as someone suggested, because she was doing much more. I can remember the meetings I had with V.C. coming up with a name. We were thinking of a few names and then she said, ‘Let’s call it: Center for Urban Ministerial Education.’ And we called it that from day one.”

Then came a flurry of gatherings with pastors and leaders from the Hispanic, African American, and Anglo communities. “A lot of folks were very supportive,” Eldin says.

Just three months after receiving the challenge from Gordon-Conwell to think about what could be done for indigenous pastors, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education opened its doors in September 1976 at the Second African Meeting House on 11 Moreland Street in Roxbury. “We started with 30 students,” Eldin remembers. “About 16 were Latinos and 12 were African Americans, and maybe one or two were White.”

Contextualized Urban Theological Education

After a year or two, V.C. left because of her work commitments at Twelfth Baptist. “I wanted the seminary to look like the city,” Eldin reflects, “so I began to pray for an individual who has credentials, and an African American, and God sent Sam Hogan to join the team.”

Sam was finishing his second master’s degree at Harvard, a Master of Theological Studies. Today Bishop Hogan serves as a pastor and a leader in Boston with the Church of God in Christ denomination.

Other workers were added, such as Naomi Wilshire, Bruce Jackson, Efrain Agosto and Ira Frazier. Doug Hall continued developing his courses in urban ministry he had pioneered with the UMY program, and they eventually became core courses for the Masters of Divinity in Urban Ministry degree, and are still offered today.

“I really was given carte blanche,” Eldin says. “I was given freedom. I had been a Sunday School man, and I knew how to organize, mobilize, and that was key because from day one I fought for some issues.” While the school did not immediately offer advanced degrees, “one of the things I wanted was that pastors and leaders would be able to take courses and that when the time came that we would get the degree component, all the coursework they had done would be counted toward that degree,” Eldin says. Eldin fought for them, and four years later, when CUME awarded its first master's degrees, students from his first class were among the recipients.

The idea of “contextualized urban theological education” soon became the underlying philosophy of CUME. To “contextualize” means you have to keep listening to the needs of the city, Eldin says.

“You have to be faithful to the reality that is there, and then you have to discern what the Spirit is doing, even in the immigration patterns. Right from day one we started classes in English and Spanish. Two years later, we saw the growth among the Haitians coming to Boston. I asked Marilyn Mason, who worked with EGC, if she would help me convene Haitian leaders.

"And what we did then became a principle. Here is what you do. You get one or two key leaders, have them convene others for a meeting, and when they get here I say, ‘Look, we are here to prepare leadership. But you need to push us. What do you want to do? How far do you want to go? Do you want a certificate or a degree program? We can do it, but you have to push us so I can push further up.’

"And of course with critical mass and the key leadership we had among the Haitians, one of the first ones who started to work with us was Soliny Védrine.”

Pastor Védrine was busy planting a church in Boston. He also worked as a bookkeeper to support his growing family. With a law degree and a recent theological degree from Dallas Theological Seminary, Pastor Sol began to teach Haitian pastors in Creole. Pastor Sol continues to serve the Haitian Christian community today through the Emmanuel Gospel Center.

“Later we did the same thing with the Brazilians. Ruy Costa was doing Ph.D. work at BU with me. Through him we convened the Brazilians and they began to come,” Eldin says. CUME began offering classes in Portuguese. Today, Dr. Costa works as executive director of the Episcopal City Mission in Boston.

For a while, CUME even offered courses in American Sign Language taught by Rev. Lorraine Anderson, when she served as senior pastor of the International Community Church in Allston.

CUME and the Quiet Revival

Boston’s Quiet Revival is understood as an unprecedented and sustained period of Christian growth in the city of Boston beginning in 1965 and persisting over five decades. As CUME got momentum, there was, at the same time, robust church planting in Boston, particularly among these immigrant populations.

In 1965, when the revival began, there were 318 churches in the city. Fifty years later, despite the fact that many church plants are short-lived and not a few mainline churches have closed; there are now more than 575 Christian churches within city limits, according to EGC’s research.

“My perspective is that we have to be discerning and faithful to what the Lord is doing. I believe the Lord is sovereign in the world, so movements of people to different places don’t just happen because they happen,” Eldin says.

“We have to ask, ‘What is the Lord doing by bringing all these people? What does it mean?’ We want to serve the city. We started with these four languages because they represented a strong Brazilian community, a strong Haitian community, a strong Latino community, and of course the bottom line, we want to teach in the language of those who are marginalized from society at that time, these people who are very gifted. So language, immigration, all this was tied to the revival.”

The move of God that started among the Hispanic churches and then ignited among other people groups, by and large identified with Pentecostalism. “The Quiet Revival is a move of God through Pentecostal churches, be they classical Pentecostal or independent,” Eldin says.

“Many of these churches were Spirit-open churches, and even when they were Baptist or otherwise, they were very charismatic. When I started CUME, the greatest majority of students were Pentecostal. The reason I teach theology or ethics is because I am concerned that all churches, but Pentecostal churches particularly, need solid theological training.” As an insider in the Hispanic Pentecostal movement, Dr. Villafañe has written extensively about this in The Liberating Spirit: Toward an Hispanic American Pentecostal Social Ethic.

One of the reasons the Quiet Revival has endured and prospered for almost fifty years and the churches continue to be strengthened is because CUME was there from the beginning.

EGC Director Jeff Bass says, “I think CUME is the most important Christian organization in the city, because you are backfilling theology into this movement that could have gotten weird, and it has not. There are a lot of strong churches today because there are so many hundreds of CUME graduates out there that have learned theology, and have learned Living System Ministry, the principles we teach here at the Emmanuel Gospel Center as well, such as the importance of unity among the churches, or that God is at work in the city and you have to join in with what he is already doing. We are impacting people to collaborate, to understand the living systems, to ask ‘system questions,’ not to be lone rangers, and to be on the lookout for unintended negative returns.”

CUME AND EGC

“The churches, CUME, and EGC,” Eldin says, “were part of the institutional ‘feeders’ God used to help nurture the Quiet Revival. The trio of EGC, CUME, and the emerging churches nurtured an amazing renewal in Boston over the past four decades.” He calls the relationship “triple nurture,” as there was an organic ebb and flow among the three living systems, each nurturing and being nurtured, shaping and being shaped.

Starting in the late 1960s, EGC began pouring resources into the immigrant church communities. EGC

created pastoral networks which are still in place today

provided state of the art street evangelism equipment used by urban churches to reach their own neighborhoods

ran a multi-language Christian bookstore that was both a supply center and a relational networking hub for urban pastors

offered a Christian legal clinic which worked to help pastors and church members with immigration issues, churches obtain tax exempt status, and church leaders negotiate red tape in renting or buying properties.

Supported CUME in training indigenous pastors to fan the flames of the Quiet Revival.

Today, through applied research and issue-focused programs, EGC equips urban Christian leaders to understand complex social systems, to build fruitful relationships and take responsible action within their communities, all to see the Kingdom of God grow in Greater Boston.

EGC is helping leaders engage issues related to gender-based violence, urban youth, public health, homelessness, urban education, and refugee assimilation, to name a few. By learning to align to what God is doing in Boston, Christian leaders are creating innovative and effective approaches to what some see as intractable problems.

CUME's ONgoing Mission

CUME, now Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary-Boston, is a seminary shaped by the Quiet Revival. But as both the revival and the seminary are interconnected living systems, CUME has also shaped the revival, giving it depth and breadth.

“One of the problems with revivals anywhere,” Eldin points out, “is oftentimes you have good strong evangelism that begins to grow a church, but the growth does not come with trained leadership who are educated biblically and theologically. You can have all kinds of problems. Besides heresy, you can have recidivism, people going back to their old ways. The beautiful thing about the Quiet Revival is that, just as it begins to flourish, CUME is coming aboard.”

To that end, CUME helps students achieve Paul’s charge in 2 Timothy 2:15, “Make every effort to present yourself before God as a proven worker who does not need to be ashamed, teaching the message of truth accurately” (NET).

A further contribution of GCTS-Boston beyond theological education is that it fosters cross-denominational and cross-ethnic collaboration by providing a safe, neutral place for emerging leaders to build close relationships. The students know each other by name, grow to love each other, and find it easier to work together on common goals. They know they are not alone. They learn that they are part of a growing network of men and women who are passionate about the Church in Boston. This collaboration strengthens and empowers each individual as each one stays connected with others.

Eldin says that CUME intentionally provides space for leadership to get together. The goal is that the emerging leadership will build relationships and that out of those relationships more Kingdom fruit will grow.

Most of CUME’s classes are held in the evenings as many students work during the day, either as pastors or in some other employment or both. In the middle of the evening there is a welcome coffee break when students gather informally around snacks.

Once, Eldin says, someone in the business office challenged that idea, thinking it would be better stewardship of both time and money to teach right through. “I said, ‘Don’t you touch that! When we get to heaven, we might find that might be the most important thing we did!’”

Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary-Boston (CUME) today serves 300 students per semester, representing nearly forty denominations and twenty countries. It has had strong and capable leadership following and expanding on Eldin’s vision of Contextualized Urban Theological Education; leaders such as Dr. Efrain Agosto, Dr. Alvin Padilla and Dr. Mark G. Harden.

CUME DISTINCTIVES

The school’s qualified faculty members work in the same ministry context as the students.

Courses are offered evenings and weekends to accommodate working students.

In addition to English, various courses are offered as needed in Spanish, French, Haitian-Creole and Portuguese.

GCTS-Boston offers master’s programs in several disciplines and Th.M.- Doctor of Ministry in Practical Theology. Nearly forty percent of the students pursue the Master of Divinity in Urban Church Ministry.

GCTS-Boston students gain the foundation and skills they need to be effective coworkers with God as he lavishly pours out his redeeming love across the city of Boston.

____________

Steve Daman is the Senior Production Advisor with the Applied Research and Consulting department at EGC.

The article was developed from a conversation with Rev. Eldin Villafañe, Ph.D., Founding Director, Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), Boston Campus of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (1976–1990) and Professor of Christian Social Ethics, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, and was originally published online by the Emmanuel Gospel Center in Nov. 2013. Excerpts were published in Inside EGC, Nov-Dec 2013, a newsletter of Emmanuel Gospel Center. With additional editing by the author, and by Aida Besancon Spencer, Eldin Villafañe, and John Runyon, the article was reprinted by Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in the Africanus Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, April 2016, p. 33.

Toward a More Adequate Mission-Speak

A church-planting movement requires mutual understanding and agreement that can only come from a common and adequate language.

A church-planting movement requires mutual understanding and agreement that can only come from a common and adequate language.

Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

This summary of a larger study offers both story and statistics on life and culture in one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the area, the study offers data on racial trends, economy, housing, education and more.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 91 — July-August 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, managing editor

Neighborhood studies reveal dynamics and principles which reflect the unique shape—culturally, geographically, and socially, for example—of a given place. By highlighting neighborhood-specific histories, heroes, and innovations, we can add story to statistics, and help complement, interrelate, and animate data in ways that better inform and inspire the development of community responses to community challenges. The Emmanuel Gospel Center has produced various neighborhood studies to this end. In recent years, we have supported the Youth Violence Systems Project by conducting research on a half dozen neighborhoods that are known to have had a history of youth violence. These studies help provide a wider framework for viewing each neighborhood as they touch on many aspects of what makes that particular neighborhood unique.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition (2013) offers both story and statistics on many facets of life in this one Boston neighborhood. Following a brief history of the immediate area, the study offers data on racial trends; facts about the current population including, for example, the breakdown of ages of the residents and how they compare with other areas; and facts about the economy, housing, and education. There are also updated, annotated directories of the neighborhood’s churches, schools, and agencies including those agencies particularly concerned with violence prevention and public safety. Fourteen tables, nine new graphs designed by Jonathan Parker, four maps, over a dozen images, and an extensive bibliography help tell the story.

In this issue of the Emmanuel Research Review, we offer excerpts from the Grove Hall study with bullet points and graphics. The complete report can be viewed or downloaded HERE as a pdf file.

Understanding the Grove Hall Neighborhood

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center

About the Grove Hall Neighborhood Study

Continuing in its commitment to foster stronger communication, agreement, and cooperation around a community-wide response to youth violence in Boston, the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) has recently released an updated research study on Boston’s Grove Hall neighborhood.

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition, copyright © 2013 Emmanuel Gospel Center, was written and researched by Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher at EGC, and produced by the Youth Violence Systems Project, a partnership between EGC and the Black Ministerial Alliance of Greater Boston. A first edition was released in 2009 and titled Grove Hall Neighborhood Briefing Document. As the first edition was produced prior to the 2010 U.S. Census, much of the information was based on the 2000 Census. By returning to Grove Hall now, not only is EGC able to study the latest numbers, but changes over the past decade may indicate either new concerns or evidences of progress.

This neighborhood study is one of six Boston neighborhood studies. The others in this series are: Uphams Corner (2008), Bowdoin-Geneva (2009), South End & Lower Roxbury (2009), Greater Dudley (2010), and Morton-Norfolk (2010).

These studies were produced as part of the Youth Violence Systems Project. Two important results of the Project are a new framework for understanding youth violence and an innovative computer model. Both of these were designed in and for Boston to enable a higher quality of dialogue around understanding and evaluating the effectiveness of youth violence intervention strategies among a wide range of stakeholders, from neighborhood youth to policy makers.

Report Overview

The Grove Hall Neighborhood Study, Second Edition, presents thoughtful information on many facets of life in this Roxbury neighborhood. Following a history of the immediate area, the study offers data on racial trends; facts about the current population including, for example, the breakdown of ages of the residents and how they compare with other areas; and facts about the economy, housing, and education. There are also updated, annotated directories of the neighborhood’s churches, schools, and agencies including those agencies particularly concerned with violence prevention and public safety. Fourteen tables, nine new graphs designed by Jonathan Parker, four maps, over a dozen images, and an extensive bibliography help tell the story.

Neighborhood History

The first 200 years of settlement (1650-1850) was characterized by farms, summer estates, and orchards, including, in 1832, the estate of horticulturalist Marshall P. Wilder who used the land to experiment with many varieties of fruit trees, plants and flowers. The name “Grove Hall” is derived from the name of another estate and mansion owned by Thomas Kilby Jones, a Boston merchant who developed the property around 1800. That estate dominated the Grove Hall crossroads for a century and later served the community for many years as a health center. The growth and decline of New England’s largest Jewish community centered in this neighborhood is documented as the most important facet of the neighborhood’s history between 1906 and 1966, and the Mothers for Adequate Welfare protests and subsequent riot of 1967 were pivotal events that had an enduring and significant impact on the neighborhood. Although, in recent years, the neighborhood has faced problems and violence, its history can generally be characterized by revitalization and economic development. This 13-page history is offered because it is valuable to understand the people and groups who built Grove Hall and helped shape its current identity.

Boundaries

The center of Grove Hall is commonly understood to be the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue with Washington Street and Warren Street. For the purposes of this study, Grove Hall is defined as the neighborhood which includes the area of the five U.S. Census tracts that surround that central crossroads. These five census tracts are 820, 821, 901, 902, and 903.

What follows is a list of the major topics covered in the study, with a few bullet points highlighting some of the facts uncovered.

Racial and Ethnic Trends

During the last decade, the number of Hispanics in this area increased from 3,414 to 5,171, an increase of over 50%, representing an increase from 20% to almost 30% of the entire population.

While the area has a Black or African American majority, the overall percentage of people in this area who are Black decreased from 73% to 64% since 2000.

Linguistic Isolation

Linguistic isolation refers to households where no one 14 and older speaks English very well, therefore facing social and economic challenges. Households in Grove Hall are more likely to be linguistically isolated than households across the nation and households across the state. Approximately 15.2% of households in Grove Hall are linguistically isolated.

Age Characteristics

Regarding age characteristics, the study shows that Grove Hall has a significantly higher percentage of young people than the city of Boston as a whole, as well as the state and nation. The area has 5,450 youth under the age of 18 years, who represent 30.6% of the total neighborhood population, compared with 16.8% in the city, 21.7% in the state, and 24% in the nation.

The number of youth between the ages of 12 and 18 in Grove Hall is 2,243 or 12.6% of the population, compared to only 7.5% in this age group for Boston overall.

Population Trends

After a steady decline in population from 1940 when the population was 30,307 to the year 2000 when there were 16,771 residents, the 2010 census shows an increase with a 6% climb over the past ten years to 17,823.

Family Structure

In Grove Hall, 71.9% of families with children under 18 are headed by single females and 7.2% are led by single men. Only about 21% of Grove Hall families with children under 18 have two parents present.

Single parent families with children under 18 in Grove Hall represent the majority of all families, 79%, compared with the national percentage of 34%, the state percentage of 32%, and the city of Boston percentage of 53%.

Economy and Poverty

The percent of people below the poverty level in Grove Hall is much higher than the city of Boston as a whole. The average of the percentages of people in poverty in each of the five census tracts is 37% compared to the city of Boston’s rate of 21%, the state’s rate of 10.5% and the national rate of 13.8%.

For youth and children under 18, 73.1% were under the poverty level in census tract 903 and 56.1% in census tract 902. This compares with 28.8% in the city of Boston overall and 13.2% for the state.

Public Assistance

There is a higher percentage of households receiving public assistance in Grove Hall than in the city, the state, and the nation. Since 2000, the number and percentage of households receiving public assistance has increased in four of the five census tracts. The Grove Hall census tract with the highest percentage of households receiving public assistance is census tract 903 with 21.7%.

Housing