BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Learning to Bring Our Whole Selves

When I only engaged my mind, I was limiting my own and others’ healing.

Learning to Bring Our Whole Selves: Nurturing Holistic Healing in Biblically Based Race Education

When I only engaged my mind, I was limiting my own and others’ healing.

by Megan Lietz, Director, Race & Christian Community Initiative (RCCI)

This is the second article of a three-part series on critical lessons RCCI is learning in its first five years of ministry. RCCI focuses on providing biblically based education to white evangelicals to nurture racial healing and justice.

"I can't let you present like that again." That's what my supervisor at the time, Nika Elugardo, told me right after I gave one of my first presentations at the Emmanuel Gospel Center. I had shared on power dynamics in multiracial congregations, a topic I wrote about for my master's thesis while serving as a research fellow at EGC.

Nika's comment blindsided me. Walking back to my seat, I felt good. I had shared how white culture can unduly influence multiracial congregations and challenged people to consider how their congregational culture may uphold barriers to authentic community.

I soon learned that it wasn't what I had presented that was the problem; it was how. I had offered a presentation with all the correct data, cited my sources, and delivered it like I'd been trained. But somehow, in the process, I had forgotten that I was speaking to whole people. Not just minds. Not just degrees. But to people who needed to be nurtured with resources beyond my narrow academic toolkit.

In retrospect, I realize I had dishonored the whole people that God created these image bearers to be.

I hadn't asked them how they were doing, and I hadn't engaged them in reflection or given them time to process what I shared. There wasn't any dialogue. There wasn't creativity. There wasn't spiritual practice. There wasn't a shared experience other than me passing on information like they were minds in the chairs.

When I walked away from the podium, I felt my presentation had been a success. But over the last five years of ministry with the Race & Christian Community Initiative, I've come to define success differently. It's not only about engaging people's minds or having a polished presentation. It's about nurturing holistic transformation.

If you had asked me five years ago how to disciple people, my answer would not have reflected my practice. I would have thought it did — because I believed it. I'd written all the papers — and gotten A's. It was in my head, but it hadn't been worked into my approaches, postures, and experiences. For all the "right answers" I could give, I didn't know how to nurture transformation.

One thing I needed to learn in this journey was how to use more effective methods of adult education: I needed to treat everyone as valued collaborators and make more room for dialogue and application. Another growth area for me — which this article focuses on — was learning how to engage people in heart, mind, body, and spirit.

Pearl via Lightstock.

Learning the impact of whole-self discipleship

Piloting our first cohort was a great learning experience for me. I was catching on to what transformative learning really looked like and how to nurture it in practice. The cohort provided a space where I could test this out.

Some of the ways this showed up in the early days were opening with spiritual grounding practices (e.g., Scripture reading and prayer), centering our time on dialogue or shared experiences, and leaving plenty of time for self-reflection. As we leaned into this, the cohorts bore fruit.

Over time, I invited others to shape the curriculum. As I did, I learned intentional practices and tools to help people engage their whole selves.

“Like any sin, racism doesn’t infect only one part of us. It seeks to make its home in every part — and it will consume us if it can. ”

I was coming to see that racism wasn't something that could be addressed by appealing solely to one's head. It wasn't only about "right knowledge." If it were, perhaps racism would have already been eradicated. The fact of the matter is that the sin of racism impacts not only our minds, but also our hearts and bodies and spirits.

Like any sin, racism doesn't infect only one part of us. It seeks to make its home in every part — and it will consume us if it can.

As a result, we need to bring our whole selves into this work so we can experience holistic healing. If we only engage our minds, we miss the greater work we need the Lord to do in us and the personal healing necessary for healthy multiracial community.

Below, I share some of the ways I’ve brought my spirit, body, and emotions into the work of racial healing and justice and encourage you to think how you can do the same.

The deeper I go, the more I recognize my own need for healing. And the more I acknowledge my brokenness and invite Jesus to help me, the more I see his healing work in my life.

Laura Cruise via Lightstock.

Bringing my spirit into addressing racism

First and foremost, racism is a spiritual issue. I say this not to over-spiritualize the problem — a tactic that has been used to uphold injustice throughout history — but to suggest tools to make practical action more effective.

One of the tools I implemented early on was a monthly day of prayer and reflection for RCCI. I use this time in many ways, from praising God to seeking his direction for ministry. I often find myself sitting with the Lord and having him reveal how I've been marred by racism or need to grow to lead RCCI more effectively. As I invite the Lord to do this work, he speaks abundantly.

Especially in the early years, he imparted lessons I needed to learn to counter the sin of racism and the impact it had on my life. He reminded me of the value of relationships and community.¹ He helped me to abide in Christ, focus on being over doing, and strengthen my God-given identity. I learned to evaluate success by obedience to him versus the standards of this world.² Though these were lessons I had learned earlier on my Christian journey, he was bringing me to a deeper level: helping me shift from being a person who knew principles for reconciliation to becoming the person who he called me to be as the leader of RCCI.

He still reveals how my ways of seeing, thinking, doing, and being have been marred by racism. He does so through his Spirit, his people, and my experiences in the world.

Through the power of his love and grace, he is changing me, healing me, and helping me relate differently to the body of Christ.

“As white people, we like to think of ourselves as free agents, independent from the impact of history, socialization, and broken systems. But in seeing ourselves as such, we are underestimating the effect of sin and the freeing power of Jesus. ”

This growth isn't something I could have thought my way into, and it's not somewhere I could have gotten by just following my heart. This is fruit born from spiritual practices: prayer, worship, reflection, fellowship, Scripture reading, and soaking in the presence of God.

These spiritual practices — and engaging these practices with people whose cultures, worldviews, and experiences are different from my own — are helping me see the ways the sin of racism influences me. The way it has distorted my perception, my assumptions, my reactions — the ways it has me bound.

As white people, we like to think of ourselves as free agents, independent from the impact of history, socialization, and broken systems. But in seeing ourselves as such, we are underestimating the effect of sin and the freeing power of Jesus.

As I invite God's liberating power into my life, the Lord helps me become more aware and mindful of how racism impacts me. This awareness helps me better evaluate if I’m following God’s way or ways that feel right because of my socialization and cultural conditioning. For example, the Lord helped me see that many of my standards for what is good or excellent have been shaped by white dominant culture. These standards aren’t necessarily bad per se, but they took on an outsized role when I imbued them with a sense of goodness, righteousness, and normalcy. This role wasn’t because of their alignment with God’s will, but because of their broad acceptance and familiarity. I used these standards to judge myself and others, following what I thought was “good” without realizing that my moral judgment was being shaped less by God’s Word and more by my cultural conditioning. Jesus helped me become aware and mindful of this in ways that helped me follow him more freely.

These days, the Lord is not only showing me areas of my boundedness and discipling me into freedom, but giving me glimpses of what it looks like to do things differently. He is expanding my imagination and inviting me into new ways of "fixing" that don't uphold racial hierarchy but nurture the radical, creative, and redemptive work of Christ.

By bringing my spirit into this work, God is changing my values, postures, and ways of being. He is doing transformative work in me. And as he does, it gives me faith that he can nurture transformation in our sin-sick society.

Pearl via Lightstock.

Bringing my body into addressing racism

In the work of racial justice, my body helps me stay honest. It offers physical indicators of what's going on inside. The churning in my stomach, heat in my chest, trembling of my hands, and dull ache in my head reveal that, for as much work as I've done to show up well in certain spaces, I'm still experiencing anxiety, tension, and stress.

Let me clarify that, as a white woman, racism will never impact me the same way it affects the bodies of people of color. The physical manifestations of discomfort that I experience are nothing compared to the embodied generational trauma, the chronic stress that contributes to disparate health outcomes, or the daily violences that accost my brothers and sisters and dishonor the image of God.

That said, all bodies can offer indicators that testify to the cost of racism. All bodies need to take time to care for themselves if we are to be sustainable in the work of building shalom.

Eating healthy, sleeping well, exercising, and seeing a doctor or mental health professional can go a long way in caring for our bodies. Creating rhythms of rest, recreation, and celebration mirrors not only biblical examples, but also supports whole-self sustainability.

When I don’t do these things, I can be stressed, irritable, unproductive, too sensitive or not sensitive enough. I’m also more likely to act out of unhealthy defaults, emotions and brokenness instead of God’s truth and will for my life. When I do take time to care for myself, my whole ways of being with God, self, and others are healthier. God uses my self-care as a part of the long but faithful healing process made possible by Jesus Christ.

I used to think of caring for oneself as good, but now I've come to see it as necessary. While I know there are many obstacles to self-care, I now pursue them less as good things to do and more as acts of worship. Acts of worship that honor God and give life.

Bringing my emotions into addressing racism³

Of all the parts of myself that I've found most challenging to engage in, it has been my emotions. Feeling seems like such a simple thing. A natural thing. Something we all learn about at an early age. But I've found that my ability to feel around race-related issues has been distorted.

I don't mean my ability to care. I feel deeply called to engage God's redemptive work across racial lines. But that said, feeling passion is only the first step. And once you take that first step, discomfort will not be far behind. Persevering through that discomfort is a much more complex challenge many white people have to learn how to navigate over time. It's this that prepares us for the more challenging work — the ongoing work — of acknowledging our own brokenness, entering into the pain of others, and lamenting before the Lord.

“While engaging the mind is needed, doing so by itself is not enough. If we only engage our minds, we miss the deeper work the Lord wants to do in us and the deeper work that is needed for us to see healing in our communities.”

Though I'm an adult, I feel like sometimes I could learn from the books I read to my 3-year-old. We talk about being happy and sad and expressing these emotions. But I'm still working on allowing myself — even learning how — to feel the pain I see in the work of racial justice.

Not long ago, I met with a Black brother who had been deeply hurt by racism within a Christian community. I wasn't meeting to talk about this experience per se, but I could sense his deep pain and saw that it impacted how he showed up in our conversation. I remember getting off the call and feeling the weight of my brother's pain.

Part of me wanted to stop and lament right then and there. But another part of me felt obligated to move on to the next thing. I had a busy day.

I did take some time to pray. As I got back to my desk, I noticed how good my work was at distracting me from my emotions. It made me wonder how often I use my work to numb the pain.

I wonder how much — even when we think we care — we are so deep into generations of socialization that has functioned to numb our consciousness that we experience invisible obstacles to feeling at all.

But by the grace of God, I notice this temptation in myself and ask the Lord to help me. At this point in my journey, I'm just working on allowing myself to feel. As I do, the Lord calls me more and more into lament, which draws me closer to him, his healing power, and his community.

Prixel Creative via Lightstock.

As I engage my emotions, I’ve taken steps toward restoring my humanity: toward feeling, towards grieving, towards doing these things that are a part of the human experience and help connect people in their humanity. As I engage my body, I feel the cost of racism and learn how to care for myself in sustainable ways. As I engage my spirit, it makes all the difference, and the Lord shows me my brokenness and does the work that only he can do to help me — to help us — heal.

While engaging the mind is needed, doing so by itself is not enough. If we only engage our minds, we miss the deeper work the Lord wants to do in us and the deeper work that is needed for us to see healing in our communities.

Reflection Questions

To what degree have you engaged your heart, mind, body, and spirit in the work of racial healing and justice? Try not to judge — just notice where you are.

What is one part of yourself you feel an invitation to engage more fully?

What might it look like for you to engage your heart, mind, body, or spirit more fully in the work of racial healing and justice?

What is one thing you can do to more fully engage that part of yourself?

Take Action

Check out these resources to nurture different parts of yourself.

HEART

Listen to songs from the Porter’s Gate, an ecumenical and multiracial artist collective, that offers songs for justice and lament (scroll down on the webpage to find) or other songs addressing racism, resistance, and justice. Notice how you’re feeling when you listen to them. Where do you resonate? Where do you feel uncomfortable? What gives you hope?

BODY

Try these grounding practices excerpted from “My Grandmother’s Hands”: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway for Healing Our Hearts and Bodies. These practices can help increase our body awareness and navigate discomfort.

Use Abby VanMuijen’s slide about how emotions can manifest in our bodies as a tool to discern what feelings you may be experiencing based on your physical responses.

SPIRIT

Use this daily examen for living as an anti-racist person as a tool for self-reflection and discipleship.

Here is a liturgy of lament focusing on racism and how it has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the pandemic seems to be lifting, the scriptures and underlying issues transcend particular circumstances. They speak into and could be adapted for current events.

Read this 40-day devotional by the Repentance Project that focuses on repenting of the history of anti-Black racism in our country. You can sign up for daily emails or download the whole guide. While written for the season of Lent, it is appropriate all year long.

We want to learn from you. What do you do to engage your heart, body, and spirit in the work of racial healing and justice?

¹ Versus being a lone ranger or so oriented on accomplishing a task or achieving that I don’t tend well to my relationships with others. These are both behaviors that are shaped by the individualism and narrow views of productivity and success that have been used to sustain racial hierarchy.

² This helped me become more aware of where social norms and practices I used to not see or find acceptable are not in alignment with God’s will. It gave me the courage to challenge them and practice a different way of thinking, doing, and being that is in greater alignment with the Great Reconciler, Jesus Christ.

³ White folks’ emotions around racism have been distorted. On the one hand, white people can become engulfed and immobilized by their emotions. For example, there is a long history of white women using their emotions — specifically their tears — to center themselves in race-related conversations and avoid uncomfortable issues. In urging folks to bring their feelings into this work, I do not intend to encourage "white tears" or other inappropriate emotional expressions. Instead, I am inviting readers to consider another way white people’s emotions have been distorted: a lack of feeling influenced by how we’ve historically turned away from the horrors of racism. I hope that in acknowledging and inviting others to reflect on our emotional numbness, we may be able to express ourselves in healthier and more constructive ways before God and community.

MLK in Boston

There’s more to Dr. King’s time in The Hub than Boston University.

MLK in Boston

There’s more to Dr. King’s time in The Hub than Boston University.

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Research, Applied Research & Consulting

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is closely associated with half-a-dozen U.S. cities, mostly in the Southeast.

He was born in Atlanta and served as co-pastor at the Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father. He led a boycott of the bus system in Montgomery and led a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham. He delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington. He led a march from Selma to Montgomery where he gave his “How Long, Not Long” speech. And he was assassinated in Memphis while fighting for the Black sanitary public works employees.

But Boston has its own share of significant sites tied to the life of Dr. King. And it’s not just Boston University.

Here’s a list of some places in Boston where you can retrace the steps of Dr. King and his legacy.

Twelfth Baptist Church

Location: 160 Warren St., Roxbury

Dr. King often attended Twelfth Baptist Church where he sometimes served as a teacher. He often preached on Sunday evenings and sometimes Sunday mornings when Rev. William Hester was away. (Dr. King’s father knew Rev. Hester.)

At Twelfth Baptist, Dr. King became friends with Dr. Michael Haynes, the youth pastor at the time. Dr. Haynes later served as senior pastor and helped plan Dr. King’s 1965 visit to Boston.

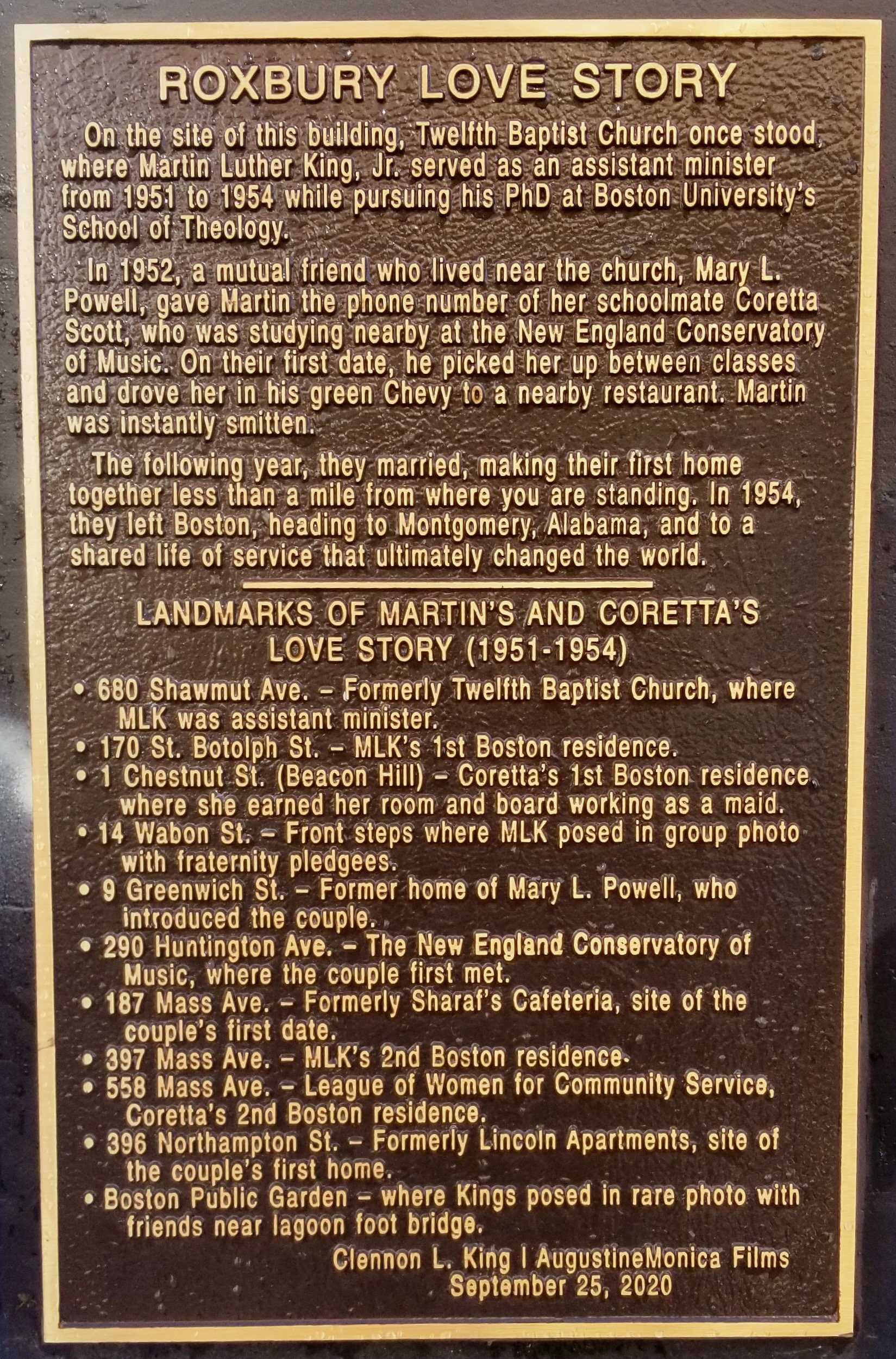

Roxbury Love Story Mural and the former site of Twelfth Baptist Church. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Up until 1957, Twelfth Baptist was located at the corner of Shawmut Avenue and Madison Street near where Melnea Cass Boulevard is today, marked by the MLK mural, “Roxbury Love Story” on the side of a new building.

Twelfth Baptist Church is currently located at 160 Warren St. in Roxbury. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Massachusetts Avenue Residence

Location: 397 Massachusetts Ave.

397 Massachusetts Ave. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Dr. King lived at 397 Massachusetts Ave. from 1952 to 1953 while studying at the Boston University School of Theology. He lived here during the time of his courtship with Coretta Scott who was attending the nearby New England Conservatory of Music and living at 558 Massachusetts Ave.

This building is near the MBTA Massachusetts Avenue Orange Line Station.

Emmanuel Gospel Center.

A plaque on the house reads:

“This house, built in 1884, was home to Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1952-53 while he was enrolled in the Graduate School of Boston University.

The building was rehabilitated in 1987 by the Tenants’ Development Corporation, a nonprofit housing organization founded in 1968 and inspired by the civil rights movement led by Dr. King.

This plaque was placed here on the 60th anniversary of Dr. King’s birth.

January 15, 1989.”

Coretta Scott lived at 558 Massachusetts Ave. before she married Dr. King. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Northampton Street Residence

Location: 396 Northampton St.

Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Dr. King and his new wife, Coretta, lived in an apartment at 396 Northampton St. after they were married in 1953 and until she graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music in 1954.

The Northampton Street building no longer exists, but a plaque marks its location. The plaque is located near what is now the site of the new Carter School, which is currently under construction, between Columbus Avenue and the MBTA Massachusetts Avenue Orange Line Station.

It reads:

Emmanuel Gospel Center.

“Newlywed Home of Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott met in Boston and had their first date in January 1952. During their courtship, Martin moved to 397 Massachusetts Avenue, and Coretta moved to The League of Women for Community Service at 558 Massachusetts Avenue. They married in Heiberger, Alabama at Coretta’s family home on June 18, 1953. When they returned to Boston, they moved into Apartment 5 in the six-story Lincoln Apartments on this site at 396 Northampton street. Sharing this one-bedroom rental, Coretta graduated from New England Conservatory of Music, while Martin completed his Boston University residency and began writing his thesis. The Kings left Boston for Montgomery, Alabama in July 1954, where they began a shared life of service and advocacy. Coretta wrote, “I came to the realization that we had been thrust into the forefront of a movement to liberate oppressed people, and this movement had worldwide implications. I felt blessed to have been called to be a part of such a noble and historic cause.”

When they were first married, the Kings lived near what is now the site of the new Carter School, which is currently under construction. The 1965 Civil Rights March started at Carter Park. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Metropolitan Baptist Church

Location: 393 Norfolk St., Dorchester

The former site of Metropolitan Baptist Church on Shawmut Avenue. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

In 1952, the pastor of Metropolitan Baptist Church, Rev. Minor, became ill and had to take some time off to recuperate. During his absence, Dr. King served as interim pastor while he was also a student at Boston University School of Theology.

At that time, the church was located at 777 Shawmut Ave. near the intersection of Ruggles Street and what is today Dewitt Drive. That church building no longer exists, but the congregation continues to meet in its Dorchester location.

Metropolitan Baptist Church. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Boston University School of Theology

Location: 745 Commonwealth Ave.

In September 1951, Dr. King began his studies in theology and philosophy at Boston University under Professors Edgar S. Brightman and L. Harold DeWolf.

With the influence of Dean Walter Muelder and Professor Allen Knight Chalmers and others at the school, he developed his philosophy of nonviolent resistance and affirmed his ultimate faith in God.

He completed his residential studies in 1954 and received his Ph.D. degree in 1955.

“The Embrace” memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King in the Boston Common. Emmanuel Gospel Center.

Boston Common and the Massachusetts State House

On April 23, 1965, Dr. King led a protest march from Carter Park to the Boston Common where he spoke against Boston’s school segregation to a crowd of 22,000.

He also spoke before a combined session of the Massachusetts Legislature at the State House on April 22.

He had previously returned to Boston in 1964 to support a parents’ boycott of the public schools, advocating school desegregation and improved quality of the schools.

Part of “The Embrace” memorial and the 1965 Freedom Plaza.

Learning As We Go

A new way of thinking helped launch me into ministry. It also changed me in the process.

Learning As We Go: A Messy Methodology Nurtured Transformation

A new way of thinking helped launch me into ministry. It also changed me in the process.

by Megan Lietz, Director, Race & Christian Community Initiative (RCCI)

This is the first article of a three-part series on key lessons RCCI is learning in its first five years of ministry. RCCI focuses on providing biblically based education to white evangelicals to nurture racial healing and justice.

I'm a planner. Every strength-based test I've taken affirms that I'm good at developing a plan, sticking to it, and getting it done. My approach to launching the Race & Christian Community Initiative reflected this skill set.

I reviewed the six-page document containing the plans to launch RCCI at the Emmanuel Gospel Center. It involved a year of research, ministry development, fundraising and relationship building that emphasized gaining understanding before taking action and underestimated how dynamic reality is.

I remember my supervisor, Stacie Mickelson, saying in essence: "That's one way you could do it, but I don't recommend it. I encourage you to start taking action now and learn as you go."

When Stacie first said this, I was a bit confused. Had she not seen my well-thought-out plan?

But more than confusion, I felt unprepared.

How could I be ready without taking the time for extensive research? Did all the degrees I had earned not testify to the need to learn before taking action in the world? Besides, I'm a white woman. I have a good chance of getting it wrong here. I want to put in the work so I can learn to effectively engage issues related to race.

“The names of the euro-descended anti-racist warriors we remember – John Brown, Anne Braden, Myles Horton – are not those of people who did it right. They are of people who never gave up. They kept their eyes on the prize – not on their anti-racism grade point average.

”

Nika Elugardo, the director of EGC’s Applied Research and Consulting department at the time, offered some wisdom I still carry with me. She said: “Megan, you don’t need to know it all. You just need to know enough to be ahead of the people you’re leading. When you are, you’re positioned to reach back and help them take the next step.”

The perspectives of my supervisors opened and invited me to a different way of learning. Instead of waiting until we "feel ready" and following the "perfect plan," RCCI now commits to learn as we go. In the process, we are transformed.

Five years into ministry, I've encountered many white brothers and sisters stuck at the same point I was: not feeling “ready” for action when, in reality, if we all waited until we “felt ready,” action would never come. I now want to reach back, offer some things I've realized about "learning as I go," and encourage them to take the next step.

Learning as you go is uncomfortable and requires risk-taking

Learning as you go — as a real-life practice — is messy and requires risk-taking. Perhaps that's why I, as a calculated planner, took some time to warm up to the idea. Or why I, as someone who wants to "get things right," avoided an approach that increased the chance of failure.

It's also not comfortable. And at first, it doesn't increase your confidence to navigate the world effectively. On the contrary, as I’ve waded into the messiness of multi-racial ministry, I’ve often felt out of control or like I don’t have a clear path ahead. I’ve felt vulnerable, frustrated, anxious, unsure, and insecure. Furthermore, this can make me want to “fix,” micromanage, or distance myself from the problem. But these reactions can be counterproductive. Learning to wrestle with the mess, sit with discomfort, take risks, and figure it out as you go are not only healthier responses, but also formative. They can help us develop the postures, perseverance, and skill sets needed to navigate the realities of race.

That said, I want to be clear that diving in as a white person is both necessary and problematic. The hard truth is that we will inevitably make mistakes and hurt people of color. In my 15 years of living across racial lines and five years leading a ministry seeking to contribute to the dismantling of racism, I’ve upset, offended, annoyed, and dishonored people of color. And it hasn’t come through things that felt like “obvious” mistakes. It has happened through moments of carelessness, oversights, blindspots, defaults. Moments when I never intended to hurt anybody. Moments when, sometimes, I didn’t even know I did.

I’ve messed up. And others – usually brave and generous people of color – were kind enough to let me know. I’ve perpetuated the very practices, narratives and ways of being I profess to stand against. I did that. And you will, too. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t take action. On the contrary, we need to learn from our mistakes, learn to repair and address the pain we have caused, and keep working toward the dismantling of racism.

Ricardo Levins Morales, a Puerto Rican artist and activist, shared:

“Anti-racist whites invest too much energy worrying about getting it right; about not slipping up and revealing their racial socialization; about saying the right things and knowing when to say nothing. It’s not about that. It’s about putting your shoulder to the wheel of history; about undermining the structural supports of a system of control that grinds us under, that keeps us divided even against ourselves and that extracts wealth, power and life from our communities like an oil company sucks it from the earth. … The names of the euro-descended anti-racist warriors we remember – John Brown, Anne Braden, Myles Horton – are not those of people who did it right. They are of people who never gave up. They kept their eyes on the prize – not on their anti-racism grade point average. … This will also be the measure of your work. … There are things in life we don’t get to do right. But we do get to do them.”¹

I encourage you to dive in. But be thoughtful about where and how you dive in. Be mindful of the potential consequences and be ready to slow down, confess, repent, and make things right.

Creative Clicks Photography via Lightstock.

Learning as you go contributes to quicker learning

When Stacie and Nika encouraged me to take a risk and learn as I go, they weren’t only helping me learn to do differently, they were actually helping me learn more efficiently. Trying and learning through experience helped me refine my ideas with my feet. It was more efficient to come up with a plan and test it along the way than to polish one before trying it.

As someone who had been conditioned to go for the "A" right out the gate, it took some time to get used to this new approach. But I found it invaluable. Not only did I learn a lot on the way, but I got a lot farther piloting my ideas than I would have if I had "perfected" them on paper. What I once saw as glorious plans now feel like a taxidermied butterfly. They look pretty but they don't fly.

One example of how this methodology bore fruit was with RCCI's cohort community. When I started the first cohort, I wasn't planning to launch a program. I just wrote a blog post and invited white people to talk about race. Little did I know God had been preparing people long before they responded to my blog post. He had placed within them a longing to wrestle with issues related to race in Christian community. Seeing this longing and how it aligned with my own, I jumped in. I didn't feel prepared and I certainly didn't know how to start a program. But we had the Holy Spirit's guidance and my supervisors' support. We also had the resources found within our inaugural community. And so this fledgling group grew into our first cohort.

What started with a handful of people has since evolved into our core program. It’s contributed to action taking and inspired testimonies of transformation. (To learn more, you can read RCCI's Cohort Origin Story here.)

While piloting the cohorts, I learned much about leadership, picked up different tools and practices, and developed meaningful relationships. Ultimately, I was launched into ministry. Though we didn’t have the big team or resources that are often associated with growth, our willingness to "try fast, fail fast, and learn fast" helped us go far.

This experience can be captured well in a quote by sociologist, historian, and author, James Loewen: "If we wait until we are ready … we may wind up old and feeble before we ever do anything. Conversely, getting out there and trying to change society can teach us some things and wind up changing ourselves."²

Learning as you go creates opportunity for collaboration

Learning as I go helped me lean into community. To be honest, I'm a bit of a lone ranger. I need a loving nudge to overcome my natural tendencies that are in tension with my Christian ideals. While "not knowing the answers" and not feeling ready could be seen as a setback, these same feelings developed a healthy fear and open posture in me. This approach nurtured collaboration and propelled me ahead.

When I first launched the cohort, I felt I was operating out of a place of weakness. I was a mother of a demanding 1-year-old, who had me up early in the morning and wanting to go to bed by 8 p.m. Leading cohorts from seven to nine left me in a situation where it was hard to give my best. During cohort conversations some nights, my tired mind would struggle to be attentive. As the facilitator, sometimes I wouldn't know what to do next. It was in those moments of feeling my own limitations — and perhaps because of them — that space was created for others to jump in. They could take the lead. They could share experiences or offer resources that may have gone unshared. They could voice questions that may have gone unasked.

What started as collaboration out of necessity became an intentional approach for RCCI. I valued collaboration in principle, of course. I spent significant time listening to and learning from leaders of color before piloting anything. But feeling my own limitations — and remembering that God didn’t design us to do this alone — helped me cement collaboration into RCCI's practice.

For example, after the first cohort, we worked with alumni to envision and try out a "next step" that would eventually become our support and accountability groups. When we piloted our multiracial workshops and community forums, we invited people of color to speak into the process and co-lead early on. While we were still learning how to collaborate well, we were committed to collaboration — and continue to learn how to do so today.

The "learn as you go approach" encouraged a practice of learning with others. Both of these are now part of RCCI’s DNA today.

Mari Yamagiwa via Lightstock.

Learning as go you nurtures liberation

One of the hardest aspects of embracing agile methodology was that it challenged — no, more than challenged — it required the sacrifice of my perfectionist tendencies.

Perfectionism is something people of all races struggle with for several reasons. But it's also something that can — and has — been used to uphold racial hierarchy.

Taking an approach that required me to address my perfectionism served another purpose: it was a means through which the Lord could continue to liberate me from one of the ways the sin of racism can operate in my life.

Taking a learn-as-you-go approach to ministry helps me not only let go of some of my perfectionism. I'm also learning to let go of control.White folks, especially, are accustomed to having more agency because of our white privilege. We can have unhealthy expectations around power because of how our racial group is dominant and centered in society. We expect power, feel entitled to it, think it is something we need.

But white people are not the Creator. God did not intend for us to have control over and above other human beings. We are all created in God's image and commanded to have dominion over the earth (Gen. 1:27-28) — a dominion of stewardship, caring, and mutual thriving so that God's shalom may reign on earth.

I know this in my head, but the desire to be perfect and the desire to control are very human tendencies.

Taking a "learn as you go" approach is working this out of me. It's been a tool of Christ’s sanctification, liberation, and healing.

The practices and postures of "learning as you go" help nurture liberation. It gets us to re-examine and release the ways we've been conditioned and open ourselves to the Lord. It helps align us with his will so that we can more fully and freely follow Jesus in a multiracial world.

“If we wait until we are ready … we may wind up old and feeble before we ever do anything. Conversely, getting out there and trying to change society can teach us some things and wind up changing ourselves.”

When Nika and Stacie encouraged me to jump in, I didn't expect to be holding on to their advice five years later. Their invitation felt like a risk — and it was — but it was one I've found well worth the reward. It's a reward not of security or ease but of Christ-like transformation.

And today, I'm still on that journey of transformation. Each step of the way, God has shown me grace.

Shelton, a member of RCCI's inaugural cohort, recently shared with me about our early years. She said: "Megan, I didn't follow you because I thought you had all the answers. I followed you because you knew you didn't. Because you were willing to journey in community and learn as you go."

Especially with Boston being a hub for education, we are often valued for what we know. But the deeper I get into Christ’s work of healing and justice, the more I realize I don’t know.

This not knowing doesn’t need to be a barrier. On the contrary, it can be a catalyst for transformation, collaboration, and liberation. If we come with a teachable spirit and humble posture, we can find a gift in uncertainty and be changed by a commitment to learning as we go.

Reflection Questions

How might these principles for learning relate or not relate with your own experience?

When might you have received challenging feedback? How have other people’s perspectives helped you to grow?

Where might you be leaning too heavily on your ability to plan, prepare, or control?

What is one area the Lord may be inviting you to “dive into” even if you don’t feel ready?

In that area, what could the dangers and benefits be of you taking a “learn as you go” approach?

¹Ricardo Levins Morales, "Whites fighting racism: what it’s about," Ricardo Levins Morales Art Studio, January 7, 2015, https://rlmartstudio.wordpress.com/2015/01/07/whites-fighting-racism-what-its-about/.

²James W. Loewen, "The Joy of Antiracism," in Everyday White People Confront Racism & Social Injustice: 15 Stories, ed. Eddie Moore Jr., Marguerite W. Penick-Parks, and Ali Michael (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing LLC, 2015), 31.

Lessons We’re Learning

RCCI’s founding director, Megan Lietz, shares three key lessons that are forming the ministry and that could serve your own pursuits of building shalom across racial lines.

Lessons We’re Learning: Three Takeaways From the First Five Years of Ministry

by Megan Lietz, Director, Race & Christian Community Initiative

As the Race & Christian Community Initiative at the Emmanuel Gospel Center celebrates five years of ministry, we’ve been intentional about reflecting on our journey. We’ve considered the lessons we’re learning, the ways we’re growing, and what we want to carry with us into the future.

RCCI’s founding director, Megan Lietz, shares three key lessons that are forming the ministry and that could serve your own pursuits of building shalom across racial lines.

We invite you to learn from our mistakes. Gain from our experiences. Or simply be affirmed in the wisdom you already know. Take a look and consider three lessons that have been transformative for our ministry and that we believe are foundational to continuing God’s redemptive work across racial lines.

Part I — Learning As We Go: A Messy Methodology Nurtured Transformation

A new way of thinking helped launch me into ministry. It also changed me in the process.

When I only engaged my mind, I was limiting my own and others’ healing.

Part III — Learning How to Pedal: Balancing “Doing” and “Being” in the Work of Racial Justice

It’s not just about what you do, it’s how you do it.

Remembering Pastor Clarence McGregor

Pastor Clarence McGregor, a beloved member of the local community, passed away in September 2022. He had served with Starlight Ministries at EGC and as associate pastor at South End Neighborhood Church for many years.

Pastor Clarence McGregor, a beloved member of the local community, passed away in September 2022. He had served with Starlight Ministries at the Emmanuel Gospel Center and as associate pastor at South End Neighborhood Church for many years.

Known as “Pastor C,” he had a heart of compassion for people who call the streets home. Family, friends, and colleagues testify to the work of God in his life.

EGC staff and friends mourn his passing but praise God for his life and ministry of love.

BPS Engagement Toolkit

The Boston Public Schools Engagement Toolkit resource includes data, opportunities for volunteers to engage, stories of church-school partnerships, a prayer guide, and more.

Boston Public Schools Engagement Toolkit

by Kylie Collins

Boston Public Schools is a dynamic school system with changing district policies, goals, and leadership.

It wants parents, community members, and churches to help. But navigating the school system and understanding the role of the Church in public education can be confusing.

The Boston Education Collaborative (BEC) at the Emmanuel Gospel Center created a toolkit to inform and provide opportunities for people to get involved and support students, teachers, and administrators.

The Boston Public Schools Engagement Toolkit resource includes data, opportunities for volunteers to engage, stories of church-school partnerships, a prayer guide, and more.

“There are countless opportunities to engage with the Boston Public Schools (BPS) and support their efforts to educate and mentor students,” said Ruth Wong, BEC director. “However, as a large, complex system, BPS can be difficult to understand, navigate and keep up with. This toolkit helps to provide direction about where to find information about BPS and its initiatives. It also suggests ideas for how you can get involved in advocacy work, volunteer, or mobilize your faith communities to participate.”

The toolkit is just a starting point for information and involvement. Visit the BEC website or contact Ruth Wong at rwong [at] egc.org for more information and ways to participate.

Kylie Collins

About the Author

Kylie Collins was a summer 2022 Applied Research and Consulting Intern at EGC. She will graduate in spring 2023 with a degree in Economic Policy Analysis from Simmons University. Originally from Columbus, Ohio, she developed a passion for supporting her community through advocacy and public education services. After graduation, she plans to work in the non-profit sector or in local government. In Boston, she has enjoyed Red Sox games, trying new foods, visiting the ocean, and making new friends.

Exploring a church-school partnership

How do you start and sustain a successful partnership with a local public school? Here is a roadmap your church can explore as it discerns its level of involvement.

Exploring a church-school partnership

There is a tremendous opportunity for churches to extend God’s love and care to the community beyond their own congregations by building meaningful relationships with local school communities. These relationships lead to mutually transformative experiences with students, staff, and families.

But how do you start and sustain a successful partnership with a local public school? Here is a roadmap your church can explore as it discerns its level of involvement.

Love Shows Up

Symphony Church in Allston partnered with Jackson/Mann K-8 School in Allston for several years before the school closed. The church served as a critical partner during the pandemic.

Love Shows Up

How one church’s long-term relationship with a school is bearing fruit

By Pastor Ayn DuVoisin

Schools faced extraordinary challenges during the height of the pandemic. Some churches helped bridge the educational gap by tutoring students.

One church that serves as a model for helping the local school system is Symphony Church in Allston. Its partnership with Jackson/Mann K-8 School in Allston was marked by a long-term commitment that was highly relational with effective pastoral leadership supporting the initiative.

The Boston Education Collaborative (BEC) at the Emmanuel Gospel Center has been key to the success of church-school partnerships like this.

“There is tremendous opportunity for churches to extend God’s love and care to the community beyond their own congregations through building meaningful relationships with school communities, which includes students, staff, and families,” said Ruth Wong, BEC director. “Through relationships, mutually transformative experiences happen, and volunteers get to experience God more deeply for themselves.”

The BEC sees a need for more churches like Symphony to embrace changing ministry strategies during the pandemic, adopting church-school partnerships as a means to engage the outsized challenges facing schools.

Symphony Church organizing the literacy room at Jackson/Mann K-8 School. [photo credit: Symphony Church]

Pushing through

Despite the uncertainty in March 2020 when the COVID pandemic hit, Symphony Church continued serving at Jackson/Mann. The church had been sending tutors to the school for seven years and had no plans of stopping.

Jackson/Mann had several community partners during the 2019 to 2020 academic year, but school officials told Symphony they were a key partner. That motivated the church to keep showing up and serving despite the challenges when the pandemic hit.

Around that time, Symphony adopted a new microchurch model which helped to galvanize church members to continue serving in the community despite social distancing rules. Throughout the summer and fall of 2020, Symphony Church leaders preached and challenged members to serve. One sermon series focused on BLESS: Begin with prayer, Listen with care, Eat together, Serve in love, and Share your story. This was part of an effort to cast a vision for a missional culture of sending out the microchurches to engage their neighborhoods even in the middle of a pandemic through initiatives such as prayer walks.

That summer, 20 church volunteers spent two hours every day helping with the school’s virtual program. Symphony also gave summer-school teachers a virtual tablet to use as a whiteboard. In the fall, even more people volunteered to tutor.

Symphony Church cleaning out and organizing school closets. [photo credit: Symphony Church]

Showing up

Partnering with local schools to help students is part of Symphony’s DNA.

In 2010, the church started meeting at the Match Charter Public School’s high school campus in Allston. The school had a system of matching volunteers as tutors to each student. Twenty tutors made a full commitment to serve for two years.

This inspired Barry Kang, lead pastor of Symphony Church, to imagine the potential impact of supporting students with additional tutoring and classroom aides in other schools. They decided to encourage the positive momentum by hosting an appreciation dinner for the tutors.

Pastor Kang said he was convicted by seeing how many issues in people’s lives sprang from early challenges, starting with literacy. Third grade, when education shifts from learning to read to reading to learn, is a critical turning point in a child’s life. These are precious years in supporting systemic change, Pastor Kang learned.

Coupled with his conviction that the “bedrock of society is in the development of the future generation,” Pastor Kang felt that a church-school partnership was compelling. The church’s biggest resource, its energetic worshiping community of college and postgraduate students, had little money but some available time. Through prayer, the church’s leadership saw education as a place to leverage their strengths.

Symphony Church hosted a teacher appreciation breakfast in May 2022. [photo credit: Symphony Church]

In 2014, they wondered whether Boston Public Schools could make use of additional tutoring support of one or two hours a week. At a gathering of pastors, Pastor Kang heard BEC Director Ruth Wong give a presentation on the program’s supportive role in assisting partnerships. Wong connected Symphony with Boston Partners in Education as well as the International Community Church in Brighton, which had been volunteering tutoring services at Jackson/Mann.

“Ruth and EGC helped us get started and helped us get better,” Pastor Kang said.

Pastor Kang said Symphony’s relationship with Jackson/Mann began with its conviction that “love shows up.” He was personally committed to the partnership as well as building direct relationships with the building principal, vice-principal, and teachers. Pastor Kang reinforced the vision for outreach to Jackson/Mann from the pulpit, and the school administration saw the fruit of the relationship.

“There is tremendous opportunity for churches to extend God’s love and care to the community beyond their own congregations through building meaningful relationships with school communities, which includes students, staff, and families. Through relationships, mutually transformative experiences happen, and volunteers get to experience God more deeply for themselves.”

Leaning in

During the 2020 to 2021 school year when schools were still grappling with the impact of COVID, 50 Symphony volunteers spent 2,200 hours tutoring at Jackson/Mann.

“That year, we were that school’s only community partner,” Pastor Kang said. “All their other partners weren’t able to pivot out of their established lanes. But we could because of the BEC’s help.”

Boston school officials announced they would close Jackson/Mann at the end of the school year in 2022, but Symphony decided to serve to the very end as it prayerfully discerns which school to partner with next.

Symphony Church cleaning out and organizing school closets. [photo credit: Symphony Church]

Symphony is energized by the multiplication potential of some of its microchurches serving in their own communities.

While many people wonder when things will go back to the way they were, Pastor Kang feels the pandemic forced the church in a new direction that is yielding kingdom fruit. He said one of the microchurch members, who was skeptical of the new model in the beginning, confided that “‘before the changes, my journey in Christ was like sitting in economy class, but now it feels like sitting in first class — no, actually it’s more like being in the copilot seat, and I have a much greater sense of ownership in this journey.’”

Pastor Kang noted a shift in the church from passivism and consumerism to more active participation as an integral part of the body of Christ and the kingdom.

Because multiplication is part of its language, Symphony hopes its relationships will create new frontiers for support in other schools. And they are partnering strategically with the BEC to explore those new connections.

Symphony’s model of community engagement has been a transforming grace for its members. The church is blessed by working with children and seeing them grow so quickly in their understanding and development. There is a gratification of seeing work they’ve been engaged in, that is clearly useful, something bigger than themselves, that glorifies God.

During the pandemic, when there has been such continual uncertainty, this outreach of serving others has been emotionally and mentally encouraging to the church, Pastor Kang said, with all the members getting to “exercise their love muscles!”

Symphony Church’s notes of appreciation for Jackson Mann staff. [photo credit: Symphony Church]

Ayn DuVoisin

About the Author

Pastor Ayn DuVoisin has been a volunteer associate with EGC’s Boston Education Collaborative initiative since 2019. She previously served as Pastor of Children’s Ministries at North River Church in Pembroke, Massachusetts, from 2000 to 2019. Over the past decade, she has been active in building the Church & School Partnership for Boston Public Schools. She is also a former board member of Greater Things for Greater Boston. She and her husband, Jean DuVoisin, have lived in Scituate, Massachusetts, for over 40 years. She is blessed by her three adult children and well-loved Golden Retriever, Sunny.

TAKE ACTION

Can you see your church engaging in a partnership like this? Here are some resources to explore as your church prayerfully discerns a potential partnership with a school in Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, or Brockton.

Mutual learning is helping Black churches thrive

Two church leaders participating in the BBCVP’s Thriving Initiative shared their strategies for serving the community and keeping their congregants safe from COVID during worship services.

Pastor Jean Louis of Free Pentecostal Church of God and Pastor Bisi Asere of Apostolic Church LAWNA meet for the first time in person after participating in online meetings for half a year. Rosa Cabán with R9 Foto for The Emmanuel Gospel Center

Mutual learning is helping Black churches thrive

Black Church leaders reflect on God’s work in Boston.

By Hanno van der Bijl, Managing Editor, Applied Research & Consulting

“I see God bringing people together, having conversations that are important that we haven’t had. We’re being more open with one another and more transparent about ways that we can partner and collaborate.”

That sentiment expressed by Gina Benjamin was echoed by others reflecting on God’s work in Boston at a recent meeting for the Boston Black Church Vitality Project.

Benjamin, social services director of the community center at Mount of Olives Evangelical Baptist Church in Hyde Park, is part of the project’s Thriving Initiative, a cohort of 10 ethnically and denominationally diverse Black churches that are located in four predominantly Black neighborhoods in the city.

Members of these churches participating in the cohort said God is using the pandemic and other challenges not only to unify and strengthen the Church, but also to create opportunities for compassion and evangelism.

The cohort meets together for two hours every other month for fellowship, peer learning, skills-based workshops and group training, and discussions about opportunities for collaborative ministry. During a meeting earlier this year, two church leaders shared their strategies for serving the community and keeping their congregants safe from COVID during worship services.

Caring for the community

At the onset of the pandemic, Fania Alvarez, who heads up The Greater Boston Nazarene Compassion Center (GBNCC), said the leadership team decided they could not stop. But they knew they would have to do things differently.

The GBNCC runs a food pantry that distributes more than 7,000 pounds of food to families in need every week. When COVID hit, people started lining up hours earlier than usual with little social distancing.

The GBNCC decided to open up a couple of hours earlier to accommodate the crowd.

“It was really challenging, but God was in the midst of it,” Alvarez said.

Launched by the Haitian Church of the Nazarene — Friends of the Humble almost 30 years ago, the GBNCC serves low-income families and individuals who have limited access to services and resources in the community.

In addition to the food pantry, the ministry runs a safety-net program, assisting people with government programs such as SNAP and WIC. The GBNCC also provides English language literacy and workforce development classes.

Once the vaccines became available, the ministry served as a vaccination clinic. The shots were a godsend, but some people were hesitant, Alvarez said.

“We had to find strategies to work with them. We had to go out and convince and educate them on the vaccine,” she said. “It wasn’t an easy time, but we made it. We can say we made it.”

Churches that want to develop a social ministry of their own need a dedicated leader who is able to manage programs and secure resources from donors and charitable organizations.

“Pray to the Lord so you can find somebody that has the heart for it,” Alvarez said.

In a meeting earlier this year cohort participants were asked: “What do you see God doing in the city?” Here’s what they said.

Managing churcH through pandemic

In 2017, the Rev. Kenneth Sims at New Hope Baptist Church started bringing bank machines into the church services.

“Some of our real spiritual-deep folk thought that I lost my mind bringing a machine to receive tithes and offerings,” Rev. Sims said. “But that was the biggest aspect of our giving.”

He also felt compelled Sunday after Sunday to tell his congregants to get a smartphone.

“It didn’t really seem spiritual at the time,” he said. “The church eventually caught on. Every Sunday — especially the seniors — would flash their smartphones and say, ‘Reverend Sims, I have a smartphone. I don’t know how to use it but I have one.’”

Then the pandemic hit. No collection plates were passed around to receive contributions. All in-person services stopped.

“I just thank God … because we weren’t scrambling,” Rev. Sims said. “That taught me one thing: to really listen to the voice of God even when it’s in opposition to what many people are thinking. Listen to God because he knows the future.”

Rev. Sims met with nurses in the church to chart a way forward. An executive committee made up of four teams was formed to oversee the church’s response to COVID.

“We knew we were coming back to church,” he said. “We didn’t know when, so we started planning so that we’d be prepared.”

A security team oversees registration, traffic, and parking. A health-and-hygiene team handles pre-screening, including handwashing, mask-wearing, and seating. A social distancing and redesign team handles seat spacing and equipment. A cleaning and disinfecting team cleans the bathrooms after each use.

Rev. Sims said members of the congregation took ownership of the various teams and made a difference.

“It got the people involved, and it wasn’t all about me. I’ve been trying for the last few years to get away from that — to stay in my role, of course, overseeing — but not having to do it directly,” he said. “People have been empowered, and they have taken off. I don’t get in their way.”

After a five-month hiatus, the church resumed in-person worship services in August 2020. Rev. Sims said the church continues to practice the safety measures it put in place.

“Our main concern was that our people remained safe,” he said.

The executive team spent many hours meeting, praying, discussing, and researching their options to balance out the physical and spiritual needs of the congregation.

“I did not believe that New Hope could survive spiritually being away from the church gathering from March 2020 to now,” Rev. Sims said. “I could not see that.”

While some members have come down with the virus, Rev. Sims said it was not due to their worship services as far as they know.

“We have not had any kind of super-spreader situations going on at New Hope since we’ve returned,” he said. “That’s been a tremendous blessing for us.”

With even more tools at their disposal than they had at the beginning of the pandemic, Rev. Sims is confident the church can keep moving forward.

“I’m just of the impression that, yes, let’s do all that we can to be safe: let’s do everything that we can, and then we’re leaving the rest up to the Lord,” he said. “What I can’t control, what I can’t power over, I leave that to the Lord.”

TAKE ACTION

The Thriving Initiative is a three-year process rooted in learning, discerning, and doing ministry. Participating churches are examining their mission and values in light of shifting social and cultural landscapes in Boston.

By deploying tools such as interview guides, congregant surveys, and ministry inventories that BBCVP designed to support churches in understanding the needs and perspectives of congregant and community stakeholders, the cohort leads in a learning endeavor that seeks to model the work of reflection that is essential in order for the Church to remain relevant and vital.

Through online articles, reports on what is being learned, videos, and data visualization, the Boston Black Church Vitality Project project will share these stories of innovation, successful strategies, and effective use of leverage points that exemplify models of prophetic leadership, community care, spiritual formation, and the pursuit of justice.

The Thriving Initiative is generously funded by the Lilly Endowment with additional support from Boston Baptist Social Union and others. For more information, visit blackchurchvitality.com.

Do you know where you’re standing?

Why EGC’s new “Fact Friday” series explores the church’s history and legacy in Boston one short video at a time.

Updated Feb. 21, 2024

Do you know where you’re standing?

Why EGC’s new “Fact Friday” series explores the church’s history and legacy in Boston one short video at a time.

by Hanno van der Bijl, Managing Editor, Applied Research & Consulting

Did you know that the African Meeting House on Beacon Hill was co-founded by Cato Gardner, a formerly enslaved man born in Africa?

Or that Twelfth Baptist Church was the spiritual home of Wilhelmina Crosson, a pioneering Black school teacher in Boston, who also was instrumental in launching the precursor to Black History Month?

How about this gem: Boston’s oldest church congregation is not downtown — it’s in Dorchester. On June 6, 1630, the First Parish Church in Dorchester was the first congregation to meet in what is present-day Boston. The First Church of Boston did not organize until about two months later.

These are just some insights from the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s new “Fact Friday” video series on Instagram.

“The city’s churches have a rich history,” said Caleb McCoy, marketing manager at EGC. “I think those legacies impact how we view the church today, so it’s important to share that information with as many as possible.”

The Fact Friday team includes Jaronzie Harris, program manager for the Boston Black Church Vitality Project, and Rudy Mitchell, senior researcher at EGC. Since February, this dynamic duo has been creating videos exploring the church’s long history in Boston, leaving EGC’s Instagram followers hungry for more.

“People who live in Boston may walk by church buildings but they may not know, one, what has gone on there in the past and, two, what’s going on here in the present,” Mitchell said.

Bridging that gap between the past and present is one of the project’s key motivators.

“It’s been fun for me to share but also to learn,” Harris said. “Doing this project is engaging me in research. I have to go and find out about these things, which I enjoy doing.”

Harris said learning about St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church’s rich history, for example, led her to discover some surprises about the church’s ministry today as she listened to a recent sermon.

“It was interesting to hear this minister preaching Black theology from a different tradition about a festival I didn’t know about,” Harris said. “I haven’t heard that type of militant preaching in Boston before.”

Caleb McCoy (right) films a recent Fact Friday video with Rudy Mitchell (left) and Jaronzie Harris (center).

The city’s Black churches have a rich legacy of gospel ministry and social action.

“Almost every time you look at one of the Black churches in the 1800s, you see they were deeply involved in the abolitionist movement and advocating for the rights of enslaved peoples,” Mitchell said. “A lot of rich history inspired continued activism in more recent times.”

The team believes the Black church’s spiritual legacy continues to buoy the community as it faces its own headwinds today.

“We are in a time that’s very racially charged right now,” McCoy said, “but it’s important to know that Black Christianity and the Black church has a legacy that’s gone before us and has a rich history in the fight for equality and justice in our own city.”

The team also enjoys parsing out curiosities such as why a church on Warren Street in Roxbury is called “The Historic Charles Street AME Church.”

In addition to digging around the past, the project has a forward-looking orientation. Boston, for example, was home to the first YMCA in the United States. What would such an innovative approach to ministry look like today?

“The Bible often tells us to remember how God was at work in the past, and we certainly can learn from history,” Mitchell said. “Even though the form and methods may change, we can be inspired to be used by God in our own time for similar purposes.”

For decades, EGC has been channeling its research and learning into specific programming and events. The Boston Church Directory, for example, demonstrates how its use of applied research is a dynamic process, bringing people in along the way.

But learning is ongoing, and it’s important to share that process, Harris said.

“I’m learning these things for Fact Friday, sure, but I’m also learning these things to better support my churches, to better understand the Boston landscape,” she said.

EGC also tries to provide a larger perspective on Christianity in Boston not just across different denominations and cultural groups but also over time. At times that research has uncovered illuminating insights.

“Historically, we saw that, between 1970 and 2010, more new churches started in Boston than in any other comparable period in Boston’s history,” Mitchell said.

Many of those churches have important stories to tell, known only by a few. Through various research projects, EGC tries to get those stories out in the open.

“We have all this historical information,” Harris said. “So how can we tell a story that is digestible for a broader audience?”

Here are some of the churches, institutions, sites, and individuals the team has covered so far:

TAKE ACTION

Follow EGC on Instagram @egcboston and watch for new reels and videos on Fridays.

What would you like to know about the history of the church in Boston? Let us know by filling out the feedback form below.

Additional Resources

Curious to learn more about the story of the church in Boston? Give these resources below a try.

Daman, Steve. “Understanding Boston’s Quiet Revival.” Emmanuel Research Review. December 2013/January 2014. Accessed January 22, 2015.

Hartley, Benjamin L. Evangelicals at a Crossroads: Revivalism and Social Reform in Boston, 1860-1910. Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2011.

Hayden, Robert C. Faith, Culture and Leadership: A History of the Black Church in Boston. Boston: Boston Branch NAACP, 1983.

Horton, James Oliver, and Lois E. Horton. Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, rev. ed. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 2000. See chapter 4: “Community and the Church.”

Johnson, Marilynn S. "The Quiet Revival: New Immigrants and the Transformation of Christianity in Greater Boston." Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation V 24, No. 2 (Summer 2014): 231-248.

Mitchell, Rudy. The History of Revivalism in Boston. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007.

Mitchell, Rudy, Brian Corcoran, and Steve Daman, editors. New England’s Book of Acts. Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007. The New England Book of Acts has studies of the recent history of ethnic and immigrant groups and their churches and a summary of the history of the African-American church in Boston.

Investing in Haitian churches and communities

The Emmanuel Gospel Center is partnering with the Fellowship of Haitian Evangelical Pastors of New England on “Pwojè Rebati” to raise funds for restoration efforts in Southern Haiti.

Investing in Haitian churches and communities

How Haitian leaders are working together to counter a broken legacy of relief aid to the battered country.

By Hanno van der Bijl, Managing Editor, Applied Research & Consulting

Four earthquakes. Four hurricanes. A cholera outbreak. Political and social upheaval. The COVID-19 pandemic.

These are just some of the crises to hit Haiti since 2010.

Billions of dollars in foreign aid remain unaccounted for, with little of it going into the hands of Haitians.

This is part of the reason the Emmanuel Gospel Center is partnering with the Fellowship of Haitian Evangelical Pastors of New England (FHEPNE) on “Pwojè Rebati” — “Project Rebuild” in Haitian Creole — to raise funds for restoration efforts in Southern Haiti. The fellowship’s partner on the ground, Ligue des pasteurs du Sud D’Haiti (LIPASH), is a group of pastors in Les Cayes, representing 3,000 churches in about 20 municipalities.

Haitian leaders identified several important needs: rebuilding churches, providing housing for families, and distributing food.

“We would like to impact the lives of people in the area spiritually, socially, and mentally, because at the end of the day, people will gather together, they will feel gratified to have a place of worship where they can express their spiritual gratitude to God,” said Pastor Varnel Antoine of FHEPNE. “From a Haitian cultural perspective, they are very religious, and they believe in worshiping God regardless of their situation. You cannot take that away from them.”

People are walking or driving for miles to go to church. More than just a place to meet on Sunday mornings, the church serves as one of the primary forms of social infrastructure for Haitians. It provides a place to worship, safety and shelter, social support and community, a second family.

“Churches are such a pillar of community in Haitian culture,” said Marjory Neret, a member of the Pwojè Rebati fundraising team. “The churches are providing far more than just the place of worship — they’re really connecting people to a lifeline. So this is actually a far more significant project than it might seem on the surface.”

In addition to rebuilding church buildings, Pastor Antoine said the team hopes to get families off the street and into two-bedroom homes to live in.

“We hope that this project, Pwojè Rebati, will be a catalyst that will motivate other organizations to help in their rebuilding efforts so that people can go back and focus on God in adoration and exaltation for who he is,” he said. “That’s what we can tackle right now.”

‘You have a big faith’

Raising money is not easy. It takes time and effort. Often the Haitian leaders who are in the best position to effectively allocate and use the funds are tied up with important and urgent demands on their time. A chasm lies between those with financial resources in countries like the United States and those experienced Haitian leaders in the middle of the action. EGC works to bridge that divide.

After an earthquake and tropical depression hit Haiti last August, FHEPNE and EGC began raising funds.

They had collected about $112,000 when EGC’s executive director, Jeff Bass, was approached by an old friend, a Boston pastor he has known for several decades. The pastor serves on the board of an organization that wanted to donate $250,000 toward Haiti relief. “That’s awesome,” Bass said. And they wanted it to be a matching gift. “That’s challenging,” Bass said with a nervous chuckle.

After some further conversation, the organization agreed to count the $112,000 that had already been raised toward the matching amount, making the challenge considerably more manageable.

Bass presented the proposal to FHEPNE. Pastor Antoine said the group had never raised that much money before.

“It’s going to be a drop in the bucket for all that has to be done,’” he told his colleagues.

Many churches in the Les Cayes area — not to mention other regions of Haiti — had been impacted. So he decided to set a goal of not just making the $250,000 matching challenge but to prayerfully push for $1 million.

Pastor Antoine’s colleagues hesitated. “‘Hmm, I don’t know, you have a big faith,’” he said they told him. But given the high construction costs, they decided to take the plunge.

FHEPNE launched the fundraiser, and EGC signed on as a fiscal sponsor as well as fundraising consultant free of charge.

EGC hired Neret, a Haitian-American leader who graduated from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. With her extensive connections in the Haitian community, Neret brings a critically important perspective to the project.

Neret has broadened the team’s outlook and experience and helped strengthen how it describes the project in addition to reaching out to hundreds of people as part of the fundraising effort.

“A lot of people, especially those who are Haitian, are pretty receptive,” she said. “They’ve been more than willing to help — most of them right away.”

A big break came when the Imago Dei Fund in Boston donated $85,000. As of early May, the team has raised $213,000. It is now pushing to get to the full $250,000 matching amount by the end of June, and hopefully further toward Pastor Antoine’s bigger vision.

“It’s a blessing. It’s the work of the Lord,” Pastor Antoine said. “I believe that he’s got his hand on it, so we need to do our due diligence, waiting for him to use us as instruments in his hand.”

Half of the challenge is raising the funds. The other half is making sure it’s spent well in Haiti.

Half of the challenge is raising the funds. The other half is making sure it’s spent well in Haiti.

The Pwojè Rebati team is discerning how it can have a distributed impact in several communities.

Part of the process is securing accurate quotes from architects and contractors for building temporary church structures. That has not come without its own heartache. The chauffeur of the architectural firm working on the project was taken hostage, and an architect’s son took his own life in despair over the situation in the country.

Pastor Antoine said the team will be accountable to small and large donors alike. The Haitian pastors in Boston and Southern Haiti are working together to create mechanisms of accountability and for wiring the money safely, which will not all go out at once.

The first phase of the project includes a church building, housing, and food distribution in one community.

“We will start with one project, one region, and see the outcome of that first project,” Pastor Antoine said. “From that point on, we will decide on the next step.”

0.6%

While billions of dollars in relief aid has been promised to help communities like Les Cayes in Haiti, success has been elusive.

The damage inflicted by the 2010 earthquake was assessed at $7.9 billion. The government of Haiti requested $11.5 billion in aid for a 10-year plan that would have helped the country not only recover but also redevelop. International donors pledged a total of $10.76 billion toward that end.

From 2010 to 2012, several countries gave $6.43 billion in humanitarian and recovery aid for Haiti. Non-governmental organizations raised an additional $3.06 billion from private donors.

Of the $6.43 billion, less than 10% went to the government of Haiti and less than 0.6% of it went to Haitian organizations and businesses in the form of grants, according to data collected by Dr. Paul Farmer’s U.N. office.

Dr. Farmer, who passed away this year, had served as a special adviser on community-based health and aid delivery to the Secretary-General of the United Nations from 2009 to 2019. His U.N. office tried to track down how much aid money was pledged, committed and disbursed to Haiti. Billions of dollars remain unaccounted for.

Without greater transparency, Dr. Farmer’s office was left to theorize that not enough aid was requested and pledged and that, of what was given, the majority of aid did not remain in Haiti. Instead, it went to contractors and non-governmental organizations based in other countries.

Haiti is not the only nation to receive such a small share of incoming aid in a time of crisis. Between 2007 and 2011, 5% of humanitarian aid went toward the public sectors of recipient countries, and of the $4.27 billion that was raised through U.N. humanitarian flash appeals in 2012, only 0.6% went directly to local organizations in various countries. Liberia suffered a similar fate in 2012 when it was struggling with Ebola.

Giving only a tiny fraction of official development assistance, or ODA, directly to a country’s political and business leaders undermines its ability to recover from disasters and thrive.