BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Join the Conversation: Honor-Shame Culture in US Cities & Churches

The dynamics of shaming affect your church community more than you might think. Guest contributor Sang-il Kim raises awareness for Boston Christian leaders to a surprising level of honor-shame dynamics in US urban culture. Join the conversation!

Join the Conversation: Honor-Shame Culture in US Cities & Churches

By Jess Mason, Supervising Editor

Before I had the pleasure of meeting Sang-il Kim, a Ph.D. candidate at BU School of Theology, I thought honor-shame dynamics were limited to specific cultures of the Far East, Middle East, and Africa. I was wrong.

My limited personal experience with honor-shame culture comes from my brief journey to China with a team of pastors. There I witnessed our cross-cultural guide go to an ATM, withdraw a wad of cash, and present it to our Chinese host, after we had unknowingly offended our Chinese friends in some way. She had received our shame and made the culturally appropriate gesture to restore our honor in their eyes.

Last month, Mr. Kim opened my eyes to the surprising levels of honor-shame dynamics now present in US cities, including Boston. Notably, he said that the American face of honor-shame dynamics today goes far beyond immigrants from traditionally honor-shame cultures.

I was inspired to brainstorm with him what it could mean for Boston area pastors—what does it look like to shepherd well amidst this emerging dynamic of honor and shame?

Mr. Kim's full article (below) aims to raise the awareness of Boston Christian leaders to honor-shame culture in their congregations, communities, and theology. EGC invites you to join him for conversation, and consider with others how you might engage honor-shame dynamics to the glory of God.

Sang-il Kim is a doctoral candidate in Practical Theology and Religious Education at Boston University. His dissertation delves into the harmful effects of shame and how teaching and learning Christian doctrines can be an antidote to them. Sang-il plans to balance teaching and research on human emotion and Christian theology, with youth and adult Christian formation in view.

White Evangelicals’ Candid Talk About Race: 6 Takeaways

What happens when a group of white evangelical Christians get together for candid conversation about race issues? Here are six takeaways from a starter conversation on April 1.

White Evangelicals’ Candid Talk About Race: 6 Takeaways

by Megan Lietz

[Last month I posted A Word to White Evangelicals: Now Is The Time To Engage Issues of Race, a call to action for beginning a journey toward respectful and responsible engagement with issues of race. As an action step, I invited white evangelicals to join me for small group conversation on race. The gathering took place April 1, 2017 at EGC. Here’s what we learned together from the experience.]

With little more than a few key questions and a spark of hope, I wasn’t sure how this first conversation would go. Under a surprise April snowstorm, I wasn’t even sure who would show up. But I sensed that God was in this. Having done my part, I was trusting God to do his.

One by one, eight white evangelical Christians filtered in. Men and women of different ages, life experiences, and church backgrounds came to the table with varied levels of awareness about race-related concerns. Against cultural headwinds of complacency and fear, these eight were ready for an open conversation about race.

Stepping Into the River

To frame our time together, I invited each person in the group to use the image of a river to depict their journey toward racial reconciliation. It was my hope that by recalling our experiences together, we could help one another imagine pathways ahead and find the support to move forward.

As people shared parts of their journey, we heard six unique stories. One man’s engagement with race issues began in the 1960s through his observation of racial discrimination at his university and his subsequent positive reaction toward the leadership of the Black Power movement. This got him thinking and eventually led him to visit a black church. One woman began to seriously think about race only weeks before our gathering because of an eye-opening grad school course.

We then used our river-journeys to reflect together on three simple questions: With regard to our engagement in issues of race...

Where are we?

Where do we want to be?

What can we do to move forward?

Takeaways

As group members began to share their experiences wrestling with issues of race and culture, they did so with relief at the opportunity to speak openly. With a life-giving mix of humility and excitement, the group gave voice to the following shared insights.

1. We Remember A Time Before We Were Aware

Each white evangelical in the room remembered a time in their life before they were aware of the magnitude and significance of racial disparities today. As one participant put it, “I didn’t realize there was an issue. It is hard to know there are racial problems when living in racially homogeneous communities.”

Confronting basic, hard realities shifted their perspective, evidenced by comments such as these from various participants:

People of color are not treated the same as white people.

Ethnic injustice was an issue even in biblical times.

People make assumptions about people’s experiences and needs based on the color of their skin.

When people just go with the flow, they are unconsciously agreeing with what is going on.

2. We Have Personal Work To Do

The group broadly agreed on the need for white people to engage in personal learning and engage issues of race more effectively. One participant shared, “There are racist systems (that need to be addressed), but I also need to do a lot of [self-]work.”

Another, who became aware of the profound impact race has on people’s lives more recently, added, “Lack of knowledge keeps me from entering the conversation. I’m still learning, so I’m insecure.” A third participant asserted that white people need to do their learning and self-work both before and during their engagement across racial lines.

3. Story Sharing is Key

Many insights affirmed the power of story sharing to bring awareness and practical guidance. It is a helpful step for us to reflect on our own stories and be willing to be honest and vulnerable. It is essential to become good listeners, giving careful attention to the stories of our brothers and sisters of color. Some of our comments were:

White evangelicals have many things to learn from communities who look different from them.

We should share our own stories about our journey toward racial justice with our fellow white evangelicals.

We should take the posture not of “rescuers,” but of mutual learners.

Sharing our own story can impact others.

Engaging with white people and people of color who are both ahead of and behind us in the journey can be useful in understanding the self-work we need to do.

4. We Need More Skills to Do Hard Conversations Well

The group identified an obstacle in their work around race: limited skill for hard conversations. They attributed the problem to a lack of good models, especially within the white evangelical community, for listening, dialogue, and engaging conflict.

One participant said that white evangelicals are not good at engaging conflict. He went on to explain that, in his experience, people often announce their opinions in ways that shut down conversations rather than invite genuine dialogue. “When people are not listening and are argumentative, it’s difficult to have the conversations that propel people forward in their journey [toward racial reconciliation].”

5. We Need Brave Spaces

When discussing what these leaders would look for in a healthy conversation, they used words like “open,” “humble,” “honest” and “authentic.”

One participant observed, “Lack of [such spaces] keeps us locked in coasting mode or in the status quo.” Brave spaces to engage in uncomfortable conversation are needed for growth.

6. Growth Requires Ongoing Community

These white evangelicals were seeking brave spaces not just for conversation, but to walk with one another in community. One participant declared his need for a “community of inquirers… that address the current social tensions.”

Another added that single events, while helpful in sparking interest and fostering growth, are less effective in supporting lasting transformation. “We need continuity…There needs to be a group who is doing this work over a length of time.”

Pilot Cohort

With a shared longing to experience new ways of listening, dialoguing, and learning in community, the group committed to experiment together as a cohort for a time. The group agreed to use two upcoming meetings to discuss Debby Irving’s book Waking Up White. We will also attend a lecture with the author.

Through this pilot cohort in EGC’s new Race & Christian Community initiative, we aim to:

Create a space where the group can try, fail, learn, and grow.

Practice dialogue that nurtures respectful and responsible engagement around issues of race.

Take Action

Are you a white evangelical Christian interested in a similar, future cohort?

Do you have advice or resources that could help our cohort function more effectively?

Do you want to speak into the development of the Race & Christian Community initiative at EGC?

Please connect with us! We invite the insights of the community and are excited to see where the Lord may lead.

Megan Lietz, M.Div., STM, helps white evangelicals engage respectfully and responsibly with issues of race. She is a Research Associate with EGC's Race & Christian Communities ministry.

Serving Cambodian Pastors

On Friday, March 4, 2005, Pastor Reth Nhar said goodbye to his wife, climbed into a car with four Cambodian friends, and headed out into the evening rush hour for the 60-mile drive north out of Providence, through the heart of Boston, to Lynn, Massachusetts. There the five made their way up to the second floor of an office building at 140 Union Street, grabbed some tea, and at 6:45 p.m., they crammed into a meeting room at the new Cambodian Ministries Resource Center.

Serving Cambodian Pastors: Every Tribe & Tongue & People & Nation

Reaching out to the mission field in our neighborhoods

On Friday, March 4, 2005, Pastor Reth Nhar said goodbye to his wife, climbed into a car with four Cambodian friends, and headed out into the evening rush hour for the 60-mile drive north out of Providence, through the heart of Boston, to Lynn, Massachusetts. There the five made their way up to the second floor of an office building at 140 Union Street, grabbed some tea, and at 6:45 p.m., they crammed into a meeting room at the new Cambodian Ministries Resource Center.

Convening on the first weekends of February, March and April this year, the class, “Evangelism in the Local Church,” is part of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s urban extension program, the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME). On Friday evenings, the 17 students from seven churches and their two instructors meet from 6:45 to 9:45. Then they are back on Saturdays from 9:00 to 4:00. The schedule is designed for busy bi-vocational pastors, like Reth, and church lay leaders who want to pursue a seminary education but need to fit it into their already busy lives.

This is the first class at CUME taught in Khmer.* Rev. PoSan Ung, a missionary with EGC, teaches in Khmer. Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Multicultural Ministries Coordinator with EGC, co-teaches in English. Asked in a survey if they would prefer to take the course in English or Khmer, some students said they were more comfortable in one language and some in the other. This, according to Gregg, “reflects the reality of a community in transition.” When a guest speaker presents in English, PoSan will translate key concepts into Khmer.

Rev. PoSan Ung established the Cambodian Ministries Resource Center last year to help support the growing ministry of Cambodian Christians in New England. There he offers Christian literature in Khmer, as well as meeting and office space. PoSan is also planting a church in Lynn, reaching out to young, second-generation Cambodians. Having lived through the Cambodian Holocaust and grown up as a refugee, PoSan is intimately in touch with the Cambodian experience. For the past ten years, he has served in various churches in New England as a youth pastor, as the English-ministry pastor for a Cambodian church, and as a church planter. Since 2000, PoSan has worked to develop a ministry that extends to church leaders in the Cambodian Christian community across New England and reaches all the way to Cambodia.

According to PoSan, “The Greater Boston area has the second largest Cambodian population outside Cambodia. However, there are merely a handful of Christians. Thus the Cambodian community is a mission field, in desperate need of enabled, equipped and supported workers.”

In 2000, this need among Cambodians was not in focus at EGC. But that was the year we teamed with Grace Chapel in Lexington to research unreached people groups within the I495 belt of Eastern Massachusetts, and to identify indigenous Christian work being carried on among them. As a result of that research, a joint Grace Chapel and EGC team began to help pastors and leaders gather together to form the Christian Cambodian American Fellowship (CCAF). The aim of the CCAF is to find avenues for training and equipping Cambodian leaders and for planning collaborative outreaches and activities that strengthen and encourage Kingdom growth among Cambodians.

Multicultural Ministries

That work also informed the development of EGC’s Multicultural Ministries program. While we have worked with ethnic churches since the ’60s, a vision was growing to do more to encourage ministry among the region’s immigrant populations who were settling not only in Boston, but in urban communities around Boston. To put flesh on this vision, Gregg Detwiler joined the EGC team.

Rev. Gregg Detwiler served as a church planting pastor in Boston for twelve years. He then served as the Missions-Diaspora Pastor at Mount Hope Christian Center in Burlington, where a ministry emerged to serve people from many nations. In 2001, he earned a Doctor of Ministry degree from Gordon-Conwell through CUME and started his multicultural training and consulting work with a dual missions appointment from EGC and the Southern New England District of the Assemblies of God.

In time, as Gregg pursued open doors of opportunity to serve ethnic communities in Greater Boston and to consult in multicultural ministry collaboration, four streams of service developed, the first being to support the CCAF.

1. Supporting CCAF

“My role in the fellowship is that of a supportive missionary who seeks to encourage and promote the indigenous development of the faith,” Gregg explains. The CUME class came out of listening to the Cambodians in the CCAF, and was a concrete response to the needs they expressed. “In the past year, we have seen participation in the CCAF broaden and deepen. By this I mean that we have come to a place where we are now dealing with some of the deeper issues hindering the Cambodian churches from expanding.” The CUME class is another major leap forward toward this broadening and deepening.

2. Multicultural Ministry Training and Consulting

Gregg lumps much of his daily work under this broad category. He provides training and consulting for churches and organizations that wish to learn how to better respond to and embrace cross-cultural and multicultural ministry. For example, in February, Gregg conducted a workshop at Vision New England’s Congress 2005 on “Multicultural Issues and Opportunities Facing the Church,” co-led by Rev. Torli Krua, a Liberian church leader and pastor. At times, Gregg is called upon to serve as a minister-at-large, responding in practical ways to needs and crises within ethnic Christian movements. He serves as a catalyst for collaborative strategic outreaches such as sponsoring an evangelistic drama outreach to the Indian community of Greater Boston. Gregg has worked to form racial and ethnic diversity teams at churches and for his denomination. He is also available for preaching, teaching, workshops, and organizational training for churches wanting to be more multicultural or more responsive to their multicultural neighbors.

3. Multicultural Leaders Council Development

On November 9, 2002, nearly 200 leaders from 16 people groups gathered at the Boston Missionary Baptist Church for an event called the Multicultural Leadership Consultation. Gregg, Doug and Judy Hall, and a diverse team worked for over nine months to plan the gathering. The event served to build relationships, heighten awareness, and launch the Multicultural Leaders Council (MLC).

The MLC is comprised of key ethnic leaders from a variety of ethnic groups, currently 15. The aim of the MLC is to find ways to strengthen Kingdom growth in each of the respective people groups, while at the same time seeking to identify with, learn from, and relate to the wider Body of Christ. Gregg explains, “In this unique context, Cambodian leaders can learn from Chinese leaders, Chinese leaders can learn from Haitian leaders, and Caucasian leaders can learn from them all—and vice versa! Also, resources can be shared that can benefit all of the ethnic movements.

“We meet once a quarter, averaging around 20 to 30 leaders. This year we are focusing most of our energies on two areas: corporate prayer and youth ministry development. In both of these, we are working with the infrastructure already in place in the city that wants to see that happen. The Boston Prayer Initiative is fostering corporate prayer. We believe that multicultural collaboration will not happen outside a climate of prayer. In the area of youth ministry development, we are working with Rev. Larry Brown and EGC’s Youth Ministry Development Project. Larry has come to meet with the MLC to let the people of the MLC influence what he is doing, while he influences the work going on among the youth in various ethnic communities by providing consulting, networking and leadership training for youth workers.”

4. Urban/Diaspora Leadership Training

In addition to his work with the Cambodian class, Gregg works closely with Doug and Judy Hall in teaching CUME core courses in inner-city ministry. “I am now considered a ‘teaching fellow.’ That is not quite a full-grown professor! I teach and grade half of the papers, I am responsible for half of the 46 students currently enrolled in Inner-City Ministry. This is a natural fit for me, as those students are African, Asian, Latin American, Jewish, Caucasian, African American—it’s a natural environment for a cross-cultural learning environment.”

A New Cultural Landscape

A flow of new immigrants into Boston and cities and towns of all sizes is altering social and spiritual realities, providing both blessings and challenges to the American church. One of these blessings is the importing of vital multicultural Christianity from around the world. This vitality has produced thousands of vibrant ethnic churches, and is increasingly touching the established American church.

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler embraces the new realities of our multicultural world and is working to find new ways to allow that diversity and cultural mix to influence our response to the Great Commission of Christ. Gregg says, “I am convinced that if churches in America effectively reach and partner with the nations at our doorstep, God will increase our effectiveness in reaching the nations of the world.” To Gregg, this hope is not merely a theoretical idea or a worthy goal, it is a reality he enjoys every working day.

[published in Inside EGC, March-April, 2005]

Boston-Berlin Partnership

The vision of EGC’s Intercultural Ministries is to connect the Body of Christ across cultural lines to express and advance the Kingdom of God in the city, the region, and the world. Building relationships and creating learning environments are essential to achieving this vision. Among its networks with urban ministries globally, Emmanuel Gospel Center is connected with Gemeinsam fuer Berlin a ministry organization in Germany since 2006, whose mission statement is: “Through a growing unity among believers in committed prayer and coordinated action, the Gospel of Jesus Christ shall reach all areas of society and people of all cultures in Berlin, so that the evidence of the Kingdom of God will increase, thus causing a higher quality of life in the city.”

Vision for an ongoing transcontinental relationship between Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC) and Gemeinsam fuer Berlin (GfB) (Together for Berlin)

I. History of Partnership

The vision of EGC’s Intercultural Ministries is to connect the Body of Christ across cultural lines to express and advance the Kingdom of God in the city, the region, and the world. Building relationships and creating learning environments are essential to achieving this vision. Among its networks with urban ministries globally, Emmanuel Gospel Center is connected with Gemeinsam fuer Berlin a ministry organization in Germany since 2006, whose mission statement is: “Through a growing unity among believers in committed prayer and coordinated action, the Gospel of Jesus Christ shall reach all areas of society and people of all cultures in Berlin, so that the evidence of the Kingdom of God will increase, thus causing a higher quality of life in the city.”

In 2008, among others Dr. Doug and Judy Hall, president of EGC, traveled to Berlin to speak at GfB’s biannual conference, TRANSFORUM. The growing interest in nurturing that partnership to share experiences and start a mutual learning process was deepened at the conference, where the Halls also met Dr. Bianca Duemling. Rev. Axel Nehlsen, the executive director of GfB, has also visited EGC twice to cast the vision of mutual learning.

In March 2010, Bianca Duemling came to Boston for two months to learn about EGC’s approaches to intercultural ministries. As a result of her experience, a partnership has developed between EGC and GfB. Bianca has served in Boston as the Assistant Director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC from November 2010-December 2013.She spent several weeks a year in Germany to enhance learning, through trainings and seminars in both cities. In April 2013, a group from Berlin came to Boston to learn more about Living System Ministries, had mutual learning sessions and were able to share what God is doing in Berlin.

II. Partnership Vision:

Although Bianca returned to Berlin in December of 2013, the desire is to continue the partnership as it is a historic opportunity to connect the experience of two cities. Emmanuel Gospel Center is committed to partner with Together for Berlin specifically in five areas of partnership:

(1) Advancing Intercultural Ministries in Berlin

Germany has never had a good reputation of being welcoming to foreigners. The immigration and citizenship laws make it very difficult for immigrants to feel at home in Germany. Until 1997 the German government denied that Germany is an immigration country despite the fact that more than 19,5% of the Germany’s population has an immigrant background. In the last 15 years, politicians and citizens began to acknowledge the situation as a huge challenge. The history of denial of the immigration reality has deeply impacted the German Churches perception of the demographic change. First, the Church is largely unaware that a considerable percentage of the immigrants in Germany are Christians who gather in vibrant immigrant churches. They are the fastest growing churches in Germany, but largely isolated from participation and involvement in the wider body of Christ. Second, the Church is generally not equipped to embrace the diversity in their neighborhood and reach out in a redemptive manner to the world on their doorsteps.

Immigrant churches play an important role in the deeply desired revitalization of the reformation heritage. Therefore, it is a huge need to connect churches across cultural lines to manifest intercultural unity as well as equip the Church to embrace diversity within their communities and beyond.

In the past five years, a small number of innovative German rooted churches and some Christian networks - including GfB - have started to work toward a growing awareness and advocate for seeing diversity as an opportunity.

(2) Development of the ‘Berlin Institute for Urban Transformation’

In Germany, there is not yet a center for urban ministry education, despite the fact that 75% of the German residents are living in urban areas. In the past year the vision to provide contextualized urban ministry education has become more concrete. This led to a partnership between GfB and the ‘Theologisches Seminar Rheinland (TSR)’ (a non-denominational theological seminary), represented by Dr. Rainer Schacke of Berlin. A working group has formed to advance the idea of the ‘Berlin Institute for Urban Transformation’. Dr. Bianca Duemling has been invited to be a key player in this development. Her experience in Boston, and EGC’s expertise in contextualized urban ministry education and their partnership with the Boston Campus of Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary (GCTS) is a very valuable resource in supporting these developments in Berlin.

(3) Applying and Testing ‘Living System Ministry’

Over the last several decades Emmanuel Gospel Center has developed “Living System Ministry”, a ministry approach based on systems thinking. LSM involves 1) learning the dynamics of key systems through Applied Research, 2) Identifying places (leverage points) in those systems where the church (broadly defined) can make a difference, and 3) equipping leaders associated with these systems and leverage points. GfB has been inspired by this approach and wants to apply it in their context. This gives EGC the opportunity to learn how LSM can be applied in a post-modern European environment and further refine their tools, concepts and best practices.

(4) Mutual Learning

Culturally and politically, Boston and Berlin are very different cities. Nevertheless, there are many opportunities for mutual learning and discovery of what God is doing in their specific cultural context. Berlin is a post-Christian city, especially because half of the city has a communist heritage. The Church in Berlin had to painfully learn how to navigate through this reality and learn to connect with people and contextually share the Gospel. Boston is facing similar challengings presented from a rising post-Christian reality. The Church in Boston can learn from Berlin’s experience and together explore how to engage in post-Christian cultures.

Boston is a diverse city, 80% of the churches have a minority background. The Church in Boston has been learning for the past 50 years what it means to become a diverse body of Christ and is well aware of the challenges and stumbling blocks in the journey toward intercultural unity. 25% of Berlin’s population is migrants.

These are two examples where mutual learning can take place. The vision is to develop a system of team learning through regularly scheduled conference calls, skype meetings and sharing written materials. The transcontinental collaborative would be strengthened through in person meetings and conferences held every 2-3 years in alternating cities.

(5) Other Collaboration Possibilities

Besides the above-mentioned main areas of partnership other possibilities of collaboration can develop depending on grant possibilities. Opportunities for comparative research and training projects can be explored. It has also been noted that other cities in Germany that have a relationship with GfB might also benefit from some of the initiatives listed above.

If you want to learn more about the Boston-Berlin Partnership and get involved, please contact Bianca Duemling.

EGC’s Multicultural Milestones

For EGC, the 2010 Ethnic Ministries Summit was not a one-time event as much as another step along the way in our participation in and encouragement of the Kingdom of God in Boston expressed in all its cultural diversity. Here are a few of the milestones for EGC as we have watched God building his church in Boston, anticipating the church described in Revelation.

For EGC, the 2010 Ethnic Ministries Summit was not a one-time event as much as another step along the way in our participation in and encouragement of the Kingdom of God in Boston expressed in all its cultural diversity. Here are a few of the milestones for EGC as we have watched God building his church in Boston, anticipating the church described in Revelation.

1969: EGC helped run a summer-long evangelistic program in inner-city parks, collaborating with 40 diverse churches and 150 workers; 7,000 hear the Gospel, 500 respond and are followed-up; this program continues for years and neighborhood churches take an increasing amount of responsibility to run their own evangelism outreach programs

1970: EGC opens La Libreria Español-Ingles, a bookstore to serve Boston’s growing Hispanic church community

1972: The Curriculum Project develops culturally relevant inner-city Sunday School curriculum, trains urban Sunday School teachers, coordinates urban education conferences

1976: EGC helps Gordon-Conwell found the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME), an urban seminary well designed to serve and develop leaders in Boston

1981: Marilyn Mason joins staff, and serves three years to start creating networks with and among Boston’s Haitian community

1985: Rev. Soliny Védrine starts work as Haitian Minister-at-Large to support the growth of the Haitian church system, and is still on staff today

1988: Rev. Alderi Matos joins staff as Brazilian Minister-at-Large and serves until 1993

1988: Rev. Judy Gay Kee starts International Networking ministry, a relationally based ministry to find, encourage, and network Diaspora missionaries serving their homelands from Boston

1989: Rev. Eduardo Maynard joins staff as Minister-at-Large to the Hispanic community and serves 11 years

2001: Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler joins staff to develop Multicultural Ministry, now EGC’s Intercultural Ministries

2002: EGC supports the development of Hispanic pastors association, COPAHNI, helping them win a grant to establish the Institute for Pastoral Excellence to train and support Latino pastors

2002: EGC sponsors the Multicultural Leadership Consultation in Roxbury to bring together leaders from major ethnic communities around Boston, and produces a companion research report called Boston’s Book of Acts

2004: Rev. PoSan Ung begins serving Greater Boston’s Cambodian community as Minister-at-Large

2007: Intercultural Leadership Consultation—400 Christian leaders from 45 ethnic and cultural groups gather in Lexington; publishes New England’s Book of Acts to document the various ethnic and cultural streams which make up the church in New England

2007: EGC’s Intercultural Ministries team begins planning for their part in hosting the 2010 Ethnic Ministries Summit in Boston

2010: EGC helped host the 10th Annual Ethnic Ministries Summit: A City Without Walls! (www.citywithoutwalls.net)

[published in Inside EGC, May-June, 2010]

2010: Dr. Bianca Duemling joins staff as the Assistant Director of Intercultural Ministries

2011: David Kimball begins serving as Minister-at-Large, Christian-Muslim Relations

Christian Engagement with Muslims in the United States

Listen in on a video conversation on Christian engagement with Muslims in the U.S. where panelists talk about positive and objectionable interactions Christians may have with our Muslim neighbors.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 87 — March 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at the Emmanuel Gospel Center, serves as host of a video conversation on the topic of Christian Engagement with Muslims in the U.S., which he hopes “will encourage many to reach out to our Muslim neighbors.” The conversation took place on February 22, 2013, and the panel was comprised of:

Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian–Muslim Relations at EGC;

Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and

Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.

In the first half of the conversation, panelists address “Positive Christian Interactions with Muslims,” which include questions regarding motivation, personal experience, peace-making, and transparency. In the second half, panelists address “Objections and Challenges to Christian Engagement with Muslims,” where they touch on militant Islam, “normative” Islam, “Chrislamism,” interfaith dialogue, and how a local church congregation might respond to a nearby mosque.

We have provided a link and brief description of each of the ten videos, which were produced by Brandt Gillespie of PrayTV and Covenant for New England in a studio located at Congregación León de Judá in Boston. At the end of this issue, we have included a short list of resources suggested by the Intercultural Ministries team of EGC.

Positive Christian Interactions with Muslims

Part One: What is your motivation for working toward positive Christian – Muslim relations?

Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director of Intercultural Ministries at EGC, introduces the subject of Christian-Muslim relations. He introduces his guests: Dave Kimball, Minister-at-Large for Christian-Muslim Relations at Emmanuel Gospel Center; Nathan Elmore, Program Coordinator & Consultant for Christian-Muslim Relations, Peace Catalyst International; and Paul Biswas, Pastor, International Community Church – Boston.

Gregg asks his guests what their motivation is for working toward positive Christian-Muslim relations.

Part Two: What are some positive ways you are personally relating to Muslims?

Gregg asks for some positive ways the panelists are personally relating with Muslims and the Muslim community. Nathan describes a “holy texts study” and other initiatives in his role as a minister at Virginia Commonwealth University. Dave talks about his love for Arab culture and his lifestyle of relating to Muslims on a daily basis.

Part Three: What are some other examples of positive Christian engagement with Muslims?

Paul describes ways he is personally relating to Muslims by building friendships, practicing hospitality, and hosting interfaith dialogues. Gregg tells the story of how a Muslim friend named Majdi cared for him when he was sick and challenges Christians to get to know Muslims on a deeper level. Dave shares a dream he has about seeing Christians and Muslims serving together, and Nathan describes some of the recent initiatives of Peace Catalyst International, including “Communities of Reconciliation” and the Evangelicals for Peace Conference held in Washington, D.C. (See http://www.peace-catalyst.net.)

Part Four: Do peacemaking Christians compromise the truth of the Gospel?

In this segment, Gregg presses his guests on the issue of Christian peacemaking by asking if this approach waters down a commitment to the truth of the Gospel. Nathan points out that the Great Commission and the Great Commandment cannot be separated but must go hand-in-hand. Nathan also suggests that not only must we be committed to the message of Jesus but also the “motives and manners” of Jesus. Dave admonishes us to be forthright in sharing the Gospel as part of our authentic Christian witness. Gregg points out the biblical mandate is to live out the doctrine of the incarnation in the way we relate to Muslims before we seek to have a theological conversation about the incarnation.

Part Five: Christian Transparency: What would you say to a Muslim who might be watching this video?

The panelists emphasize the importance of being transparent about our identity as followers of Jesus. Paul speaks of being upfront about who we are (followers of Jesus) and what we want to do (to bear witness to him). Dave speaks about how there are individuals on both sides that may seek to broadly demonize the other side, and we are seeking to counter this. The segment ends by asking each of the panel members to share a word with any Muslim friends who might be watching the video.

Objections & Challenges to Christian Engagement with Muslims

Part One: What about militant Islam?

Gregg frames the subject of challenges to Christian engagement with Muslims in the U.S. by referring to a continuum of response from hostility to naivety. Panel members respond to question: What about militant Islam? Nathan reminds us that militant religiosity is not the sole property of Islam, nor is it as universal among Muslims as some Christians seek to paint it. Dave warns us about the dangers of stereotyping others and the importance of not being paralyzed by fear and hostility. Paul shares his perspective about militant Islam from a South Asian perspective.

Part Two: What is normative Islam?

Gregg asks his guests to respond to the question: What is normative Islam? Dave responds to the question with a question: What is normative Christianity? Paul points out that just as many Christians misunderstand Islam, many Muslims misunderstand Christianity. Nathan reminds us that Muslims themselves should answer the question of normative Islam rather than Christians.

Part Three: Are you in danger of becoming a “Chrislamist”?

Gregg explores with panel members the possibility of compromising Christian truth in the process of promoting interfaith relationships with Muslims. Various subjects are explored, such as “the Common Word” initiative and the threat of being labeled as “Chrislamists.” Gregg concludes by pointing to Jesus as our model when he came “full of grace and truth.”

Part Four: What is the value and limitations of interfaith dialogue?

Gregg explores with panel members the question: What is the value and limitation of interfaith dialogue? Paul underscores how dialogue is the only way to overcome misunderstandings on both sides. Nathan describes how dialogue can be a form of hospitality and lead to authentic friendship. Dave emphasizes the need for discipline and commitment in the dialogue process and that interfaith dialogue (also known as “meetings for better understanding”) can open doors and create space for God to work.

Part Five: What steps could be taken by a church that is in close proximity to a mosque?

Finally, the panel explores the question of how a local church might respond to a mosque that is in close proximity. Dave counsels that a good starting point is for a church to get some good training. Nathan discusses the posture of the church by admonishing with the truism: “One cannot fear what one has chosen to love.” Gregg tells a story of dropping by a local mosque to meet the Imam and some surprising lessons learned in the process. Paul advises that churches should not view a mosque as a threat but as an opportunity for Christian witness.

Resources

The following resources have been suggested by the Intercultural Ministries department of EGC.

Bell, Stephen & Colin Chapman editors. Between Naivety and Hostility: Uncovering the best Christian responses to Islam in Britain. Crownhill, Milton Keyes: Authentic Media, 2011.

Goddard, Hugh. Christians and Muslims: From Double Standards to Mutual Understanding. London: Routledge Curzon, 2003.

McDowell, Bruce A., and Anees Zaka. Muslims and Christians at the Table: Promoting Biblical Understanding among North American Muslims. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Pub., 1999.

Metzger, Paul Louis. Connecting Christ: How to Discuss Jesus in a World of Diverse Paths. Nashville: T. Nelson, 2012.

Nichols, Laurie Fortunak., and Gary R. Corwin. Envisioning Effective Ministry: Evangelism in a Muslim Context. Wheaton, IL.: Evangelism and Missions Information Service, 2010.

Peace Catalyst International www.peace-catalyst.net

Tennent, Timothy C. Christianity at the Religious Roundtable: Evangelicalism in Conversation with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002.

Volf, Miroslav. Allah: A Christian Response. New York: HarperOne, 2011.

Developing Safe Environments for Learning and Transformation

Do you want to see transformation in your organization? You might want to give some thought to the importance of creating a safe environment, where your team can learn together to trust, practice confidentiality, become good listeners, stop judging, and develop a culture of patience, forgiveness, and celebrating the best in one another.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 80 — July 2012

by Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler, Director, Intercultural Ministries, EGC

I would like to address a question that we have been asked over and over again by Christian leaders and organizations that we have consulted and collaborated with in our work. It goes something like this: How does our organization (or church, denomination, school, etc.) develop a safe environment where our capacity to see personal and corporate transformation in and through our organization (church, denomination, school, etc.) is greatly enhanced? Or to put it another way, how can we experience transformation in our organization so that we have greater capacity to be an agent of transformation in our world?

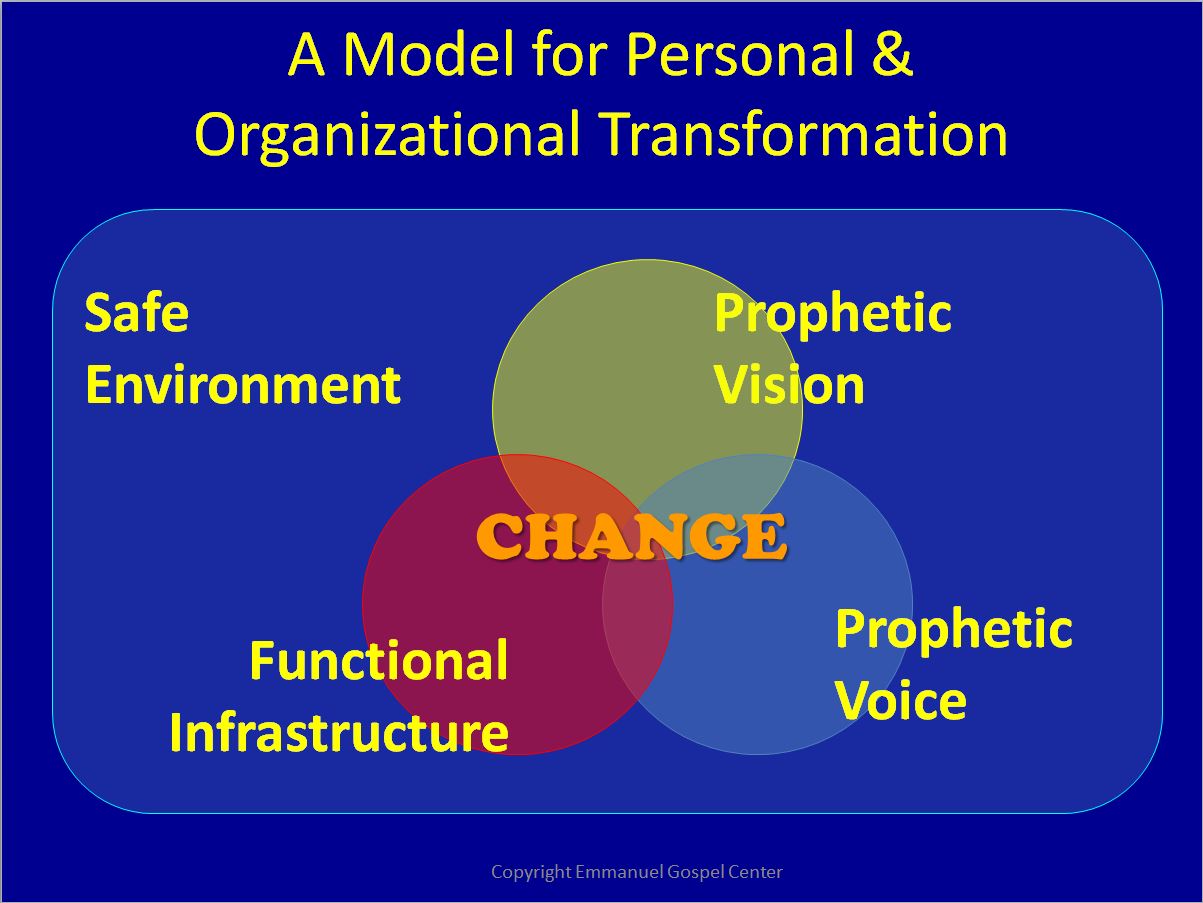

A Model for Personal and Organizational Transformation

Over the past decade, we have with consulted many organizations on the topic of organizational change. In this process, I have often shared a model—or archetype1 — that describes the elements necessary for personal and organizational transformation. I say “personal and organizational” transformation because it is impossible to have one without the other. In our context, we often apply these principles to intercultural work but they are transferable to any desired change.The elements involved can be illustrated in the following Venn diagram:

Figure 1: Model for Transformation

A brief definition of each element follows:

Prophetic Vision is seeing God’s intention for a given situation and seeing the present reality as it really is. Our primary source for prophetic vision is the Word of God, but there are other sources that are also important: the community of faith, the leading and illumination of the Holy Spirit, and social/systems analysis. This prophetic seeing will always reveal a “gap” representing the distance between God’s high calling and where we are in relationship to that high calling. This prophetic seeing must be done with humility, recognizing that as humans we “know in part and prophesy in part.” Hence, prophetic vision is best done in community where others are permitted to share their perspective to help the learning organization fill in the picture as completely as possible and to arrive at “shared vision.”

Prophetic Voice is declaring what we believe God would have us do at this point in time and space. Like prophetic vision, prophetic voice must also be shared and affirmed by a particular Christian community/organization for it to have any traction. While prophetic vision and prophetic voice can arise from anyone within a given Christian community/organization, it must be embraced and endorsed by the “authorizing voice” of that community/organization for it to gain legitimacy and traction.

A Functional Infrastructure must be put in place to carry out the prophetic vision and voice. The core of this infrastructure is an aligned functional team and the necessary support structures to do the work.

A Safe Environment is the necessary context for any and all three of the elements above to work and, hence, is perhaps the most important of the four elements. It is also, in my experience, the element most missing in Christian ministry, and the one that most often derails personal and organizational transformation. A safe environment is necessary for a community/organization to come together to understand prophetic vision, agree on prophetic voice, and build and maintain a functional infrastructure. A safe environment involves establishing, honoring and maintaining honest and loving relationships that have the capacity to sustain and learn from the inevitable conflicts that always arise in the journey of transformation.

Reflections on How To Develop a Safe Environment

The main question of this paper deals with this fourth element: a safe environment. Time and time again in our consulting practice, we hear our clients say something like this: “We clearly see the necessity of creating a safe environment for learning and transformation but we have one question, how exactly do we develop a safe environment?” What follow is a first step in attempting to answer that question.

What a Safe Environment Is and Is Not

Before answering that question, however, let’s first describe what a safe environment is and is not.

When I am consulting with a Christian group, I often get the group to reflect on this question by taking them to what I call “the most unpracticed verse of the Bible”—James 5:16. I read to them the verse from the New International Version: Therefore confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be healed. Or, my preferred rendering of this verse from the Message paraphrase: Make this your common practice: Confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you can live together whole and healed.

I then ask them a series of questions: Do we really “do” this verse in the church? Is it our “common practice”? The answer, “No, not so much.”

Then I follow with, “Why don’t we practice it?” The reply: “Because people don’t feel safe enough to do it.”

I then ask, “What would it take to make it safe enough to actually do it, to make this our common practice? What are the qualities that describe a safe environment?” The lists of qualities are always very similar, things such as:

Trust

Confidentiality

Being a good listener

Not judging others

Patience and longsuffering

Considering the best in one another

Not looking down on those who confess their sins/temptations/weakness

Not “defining” others by "freeze-framing” their identity by the sins/temptations they confess

Avoiding “cross-talk” (being too quick to give unsolicited advice to others)

Focusing on our own “stuff” rather than on others' “stuff”

Gaining trust and asking permission before attempting to speak into someone else’s life

A commitment to one another’s growth

It is also important to explicitly state what a safe environment is NOT. Many people identify the elements above but still misconstrue what a safe environment is because they do not understand the subtler elements of what a safe environment is not.

A safe environment is NOT:

A pain-free environment (growth is often painful)

Only about “me” feeling safe (it is also about helping “others” feel safe)

Uniformity of opinion (a truly safe environment welcomes different perspectives)

A permission slip for being obstinate, unyielding, and unwilling to work for the common good

A “free-for-all” for expressing raw emotions without considering the effect this sharing will have on others

Steps To Developing a Safe Environment

After describing what a safe environment is and is not, the next issue is how to get there. It is one thing to be able to describe a safe environment, it is another thing altogether to be able to create and nurture it. The following diagram describes the process I have observed in creating, nurturing and reproducing safe environments.

Figure 2: The Process of Creating & Reproducing a Safe Environment

Let’s now describe each of the stages of the cycle in more detail.

1. Willingness: A Community/Organization That Desires to Create a Safe Environment

The first step required to enter this journey is “willingness.” As the common quip goes, “A man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still.” Not many high-level organizational leaders will say that they do not want a safe environment within their organizational culture, but many simply have never experienced a safe environment themselves to the degree that they can provide the necessary leadership to cultivate it within their organization.

So the first step, plain and simple, is to find an organization or a community or (more likely) a subset within an organization/community that is willing to pursue a greater intellectual and experiential understanding of what a safe environment really is. In some cases—in a highly dysfunctional organization, for instance—the starting point may necessitate seeking out a safe environment outside of the organization.

2. Skilled Leadership to Guide in Nurturing a Safe Environment

The importance of skilled leadership cannot be overstated. This leadership may come from within the community or from outside it. The real issue here is the quality of leadership. There are certain prerequisites that a leader must have in order to serve as a guide to others in a journey toward a safe environment.

The first and foremost indispensable quality is that the leader must have already experienced the power of a transformational safe environment herself. It is impossible to reproduce and to guide others in what we ourselves have not experienced. The best guides are those who have tasted deeply of the refreshing waters of a safe environment for themselves.

The second quality is that the leader must be whole enough.2 “Whole enough” to have a healthy self-awareness, to appropriately share their journey with others, and to assist others in their journey. The term “whole enough” means that the leader is self-aware of her own brokenness and has already taken significant steps in her own healing journey. Some of the characteristics of a “whole enough” leader are as follows:

The whole enough leader is one who knows and can articulate her own self-identity in all of her complexity—good, bad and ugly. This self-awareness is demonstrated in her ability to see that she is (as we all are) “wonderful, wounded and wicked” and that God has taken this total package and has begun a process of healing and transformation. As such, the whole enough person can freely acknowledge her brokenness while at the same time seeing her goodness as a beloved child of God made in his image.

The whole enough leader is one who has learned how to appropriately share his own healing journey as a gift to others. As the whole enough one is secure in the love of God, he is able to share not only his strengths with others but also his weaknesses. As weaknesses are shared, others are called out of darkness and hiding into a place of safety, light and healing.

The whole enough person has been exposed to a safe environment to a sufficient degree that she understands the structural and spiritual elements necessary for nurturing a safe environment for others. In other words, the whole enough person is familiar enough with the air of a safe environment to recognize what it feels like and is skilled enough to know how to foster such an environment for others.

3. Group Learning About the Qualities of a Safe Environment

It is not enough for a leader to merely embody a safe environment; he must also lead a group of willing souls to consider together what a safe environment is and is not, what it looks like and feels like.

The aforementioned exercise (Group Reflection on James 5:16: confessing our sins to one another) is one of the most effective means I have found for leading a group into a better shared understanding of the qualities that comprise a safe environment.

Another technique is to get members of the group to consider the safest environments they have every encountered in their lives—places where personal and corporate transformation was made possible—and to get them to describe the qualities that were present in those environments.

4. Skilled Leadership that will Model & Maintain a Safe Environment

Once the group has reflected together and has a shared vision of what a safe environment looks like, the leader must lead the way by modeling a willingness to be vulnerable in sharing his own journey. The leader must be willing to share personal testimony that is authentic, transparent and bears witness to the power of transformation within a safe community. Not only must the leader model this, he must remind the group of the qualities of a safe environment and establish some basic ground rules that can help maintain it.3

It is also important to add here that creating and maintaining a safe environment is not like taking a straight-line stroll to the top of a mountain, but is more like a circuitous path of hills and valleys. It is often hard work because it involves fallen creatures that sometimes rub one another the wrong way. In truth, a journey toward a safe environment is not for the fainthearted; it requires ample supplies of humility, long-suffering, repentance, grace, and growth. It is important for participants to understand that this is the nature of the journey and that this reality, in fact, is part of what makes it transformational.

5. Reality Check: A Community/Org that is willing to be Honest About Where They are in the Journey

As a group reflects together on what a safe environment looks and feels like, and as the leader models and seeks to nurture a safe environment, the group will naturally begin to reflect on whether their group and their larger organization/community is a safe place. This sober assessment needs to be encouraged. If a community or organization is unwilling to honestly evaluate where they are in the journey, there will be little hope to see progress within the larger community. In many cases, safe environments must first take hold in smaller subsets of a community/organization before the larger community can be affected to any significant degree.

6. Continued Practice Through “Action-Reflection” Learning

The task of creating and nurturing a safe environment is not a destination but a continuous journey of “action-reflection.” Action-Reflection learning means that there is continuous effort given to putting into practice the qualities of a safe environment and continuous commitment to reflection, learning and evaluation throughout the journey. We learn how to be a safe community by practicing.

7. Reproduction: Members of the Community/Organization Reproduce Safe Environments in their Spheres of Influence

As members of a community/organization taste of the transforming power of a safe learning environment, they will naturally be drawn to bring its influence into their spheres of influence. In fact, I have found that people who have tasted of a safe environment will have a thirst for more and will want to bring it to others within their community/organization and beyond. This point goes back to the Genesis design that God’s creatures “reproduce after their own kind.”4 People who have experienced a safe environment, making personal and corporate transformation possible, will naturally seek out other willing souls and begin the cyclical process described in this paper over again.

Conclusion: Make this your common practice

When the three elements described in the Transformation Model (Figure 1) are practiced within the context of a safe environment, personal and corporate transformation is made possible. Examples of this transformation abound in both the personal and corporate spheres. I have experienced this in my own life, in our own work in Intercultural Ministries, and in our consulting with other organizations. A familiar example—on the personal level—that many people in our society would recognize is Alcoholics Anonymous, but there are many others.5

FOOTNOTES

1 In the discipline of Systems Thinking, a systems archetype is a structure that exhibits a distinct behavior over time and has a very recurring nature across multiple disciplines of science. The foundational text that Systems Thinkers often refer to is The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, by Peter Senge (Currency Doubleday: New York: 1990).

2 I learned the term “whole enough” as a participant in a healing ministry called Living Waters. Living Waters is one of the most effective programs I am aware of in nurturing a safe healing environment, especially for those who have experienced relational and/or sexual brokenness. To learn more about Living Waters, visit http://desertstream.org.

3 These qualities and ground rules were mentioned previously in this article under the subheading “What A Safe Environment Is & Is Not.”

4 Genesis 1:11-12

5 For copies of these case studies please contact the author.

Rev. Dr. Gregg Detwiler is the Director of Intercultural Ministries at Emmanuel Gospel Center. The mission of Intercultural Ministries is “to connect the Body of Christ across cultural lines…for the purpose of expressing and advancing the Kingdom of God… in Boston, New England, and around the world.” Gregg works with a wide cross-section of leaders from over 100 ethno-linguistic groups. His ministry largely involves applied research, training, consulting, networking, and collaboration, especially related to intercultural ministry development.

Prior to joining the staff of EGC in 2001, Gregg served for 13 years as a church planter and pastor of a multicultural church in Boston and was elected as the overseeing Presbyter for the Northeast Massachusetts Section of the Assemblies of God. He served for five years as the Pastor of Missions & Diaspora Ministry at Mount Hope Christian Center in Burlington, Massachusetts. He earned his Doctor of Ministry in Urban Ministry in 2001 from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Ministry in Complex Urban Settings. His thesis, Nurturing Diaspora Ministry and Missions in and through a Euro-American Majority Congregation, has provided much of the direction of his ministry in recent years. Raised in Kansas, Gregg graduated from Evangel University and the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary in Springfield, Missouri. Gregg and his wife, Rita, live in the Boston area and have three children.

Click to Learn more about EGC's Intercultural Ministries.

Sol's Story: Come to Boston Brother! We Need You!

“In June of 1972, I was discouraged because a year had gone by since I had graduated from seminary, and I hadn’t raised a penny to go back to Haiti, which had been my goal. So after preaching at a church in New York City, two ladies asked me whether they could join my wife and me for a night of prayer.

“In June of 1972, I was discouraged because a year had gone by since I had graduated from seminary, and I hadn’t raised a penny to go back to Haiti, which had been my goal. So after preaching at a church in New York City, two ladies asked me whether they could join my wife and me for a night of prayer. We agreed, and I said, ‘Please ask the Lord to tell me what to do! I heard the call for the ministry, but now I have been trying to raise funds to go to Haiti and I cannot raise any money. If he has something else in mind, let me know.’”

Soliny Védrine was born in L’Asile, Haiti, one of seven children of a tailor, Sauveur Védrine, who, at great financial sacrifice, sent Sol away to school in Port-au-Prince at age 14. Sol eventually graduated from the university with a law degree, married, and came to the U.S. to study at Dallas Theological Seminary. But then, Sol hit an impasse.

“By the time the two ladies left, we were tired and hungry. We were glad we prayed, but we were glad they left! That afternoon, one of the sisters came back and said, ‘We have found the answer to your prayer.’ I wondered, was it Haiti? Miami? The sister said, ‘Boston.’

“‘Boston!’ I said. ‘How do you know?’ She said, ‘Mr. Jean-Pierre, who lives in Boston, just came to spend the weekend with us. And he keeps complaining that Haitians are pouring into Boston by hundreds yet there are no churches. So I tied up his complaint with your request!’

“She put me in contact with Mr. Jean-Pierre, who said, ‘Come to Boston! We need you. Haitians are coming from New York to Boston. You should come, brother. Come!’”

Six months later, Sol and Emmeline obeyed God’s call to go to Boston. There they found two small Christian fellowships serving a rapidly growing population of Haitians. Assuming their full-time job was ministry, Sol and Emmeline began to meet with Haitian families to share the Gospel and their dream about starting a church. But when their first baby was due and they had no money, Sol took a secular job as a welder for eight months and then as a bookkeeper for eleven years, while working many hours developing the church.

Meanwhile, Haitians continued to move to Boston, and by the 1980s, new churches were starting every few months. Marilyn Mason, a missionary with EGC, began to build relationships among the Haitian pastors, and soon recognized that Pastor Sol had a strong vision to see pastors working together for effective, city-wide ministry. She asked Doug Hall, EGC’s director, if he couldn’t find a way to help Sol leave his accounting job to dedicate himself full time to helping grow Haitian churches. Several Haitian leaders said the same thing, so Doug made the call.

“We met for lunch and Doug talked to me about whether I would be willing to leave my accounting job and come by faith to the Gospel Center to begin these connections,” Sol says. “The strange thing was that that was my prayer, too! It was my dream to create a forum where pastors could have fellowship and discuss problems. On November 4, 1985, Sol joined EGC as Minister-at-Large to the Haitian Community.

Today, Boston has the third largest Haitian community outside Haiti, behind Miami and New York City. There are about 200 Haitian churches in New England, with about 60 in Greater Boston supporting a population of over 70,000 Haitians. EGC’s Haitian Ministries International works to encourage and strengthen Haitian pastors in Boston and to facilitate Haitian churches working together to serve others.

Pastor Sol’s work includes counseling and consulting with pastors and ministry leaders in Boston and across the Haitian diaspora; assisting Haitians immigrating to Boston, especially since the earthquake; and organizing evangelistic, discipleship, and training programs that serve the Haitian community in Boston and beyond.

Pastor Sol also teaches seminary classes for emerging Haitian leaders at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Boston campus, and he continues to serve as senior pastor of the Boston Missionary Baptist Church, which he and his wife founded in 1972.

by Steve Daman

Mutual Empowerment of Christian Leadership Across Culture

Cultural misunderstandings, theological controversies, and power issues influence our relationships and encounters between churches of different ethnic backgrounds and denominations.

by Bianca Duemling, Intercultural Ministries Intern, Spring 2010

A City Without Walls, the April 2010 Ethnic Ministries Summit in Boston, was a big and joyful event. The seminars and plenary sessions were encouraging for some and challenging for others. But overall, it was a powerful celebration of the diversity and beauty of the Body of Christ. Many people felt that worshipping together was like a glimpse of heaven, a taste of how it will be when all people come together before the throne of God from the North and South, the East and West.

Such experiences and conferences are indeed important for reminding us of the beauty and power of the Body of Christ, as the reality of everyday relationships is too often far from united or powerful. Cultural misunderstandings, theological controversies, and power issues influence our relationships and encounters between churches of different ethnic backgrounds and denominations.

Having studied and been part of the developing relationships between immigrant and mainline churches in Germany for the past five years, two questions are always in my mind when I am in an intercultural church setting, such as the Summit. First, how can Christians overcome the ethnic segregation in our countries and be role models in living out unity in diversity? And second, how can relationships among cultural groups and churches be transformed from conflict or oppression to equal partnerships?

There are no simple and clear answers to these questions. The relationships are complex. Oppression and conflicts are passed down from history. For that reason, I am not in a position to provide answers, but I want to share my observations and thoughts. Needless to say, these are limited to my own white-Western perspective and so I am open to any disagreement and discussion.

During the Summit, I became aware of a challenge I never saw so clearly before.

There are two kinds of realities in our society, our universities, and our churches. The first reality is that we are in the midst of sweeping demographic changes. North America—but also Western Europe—is becoming more colorful. It is a fact that white, Anglo Americans have been the majority culture for the longest part of America’s history. In just a few decades, the whites will be a minority. This will be true for the society as a whole, but also for the churches. Over the past years, there has been a constant decrease in white Christianity and a continuing increase in the number of churches of people of color and various immigrant churches, the very churches in Boston that have led the Quiet Revival. Additionally, some of the larger suburban churches are rapidly diversifying ethnically.

The second reality is that while white Christians are numerically not a majority anymore, especially in urban areas, they hold disproportionally key leadership roles. Moreover, Anglo American churches have never spent as much money on their buildings, ministries, or staff as nowadays. So far, none of this is new to me, but in my analysis of the situation, I was somehow only focusing on how the dominating culture needs to create space for other cultural expressions of faith and leadership, how we need to foster equal partnerships, to empower leaders among people of color, and to share economic resources and access to power. All of this I am still convinced is crucial. But there is another challenge to it. As the demographic reality shows, there will be a natural change so that in a few years, white Christians will be the minority. It is hard to predict the future, but I sense a danger that there is little shift from oppressive to equal relationships, but our roles are only being interchanged.

Having an isolated white Christian minority in a few years would be really counterproductive as the painful segregation of the Body of Christ might only increase. There is a need for mutual empowerment. As a white Christian, I need to be empowered to be a witness to my people, who are less and less interested in the Gospel. But at the same time, I need to empower non-white Christian leaders, as they have been marginalized and oppressed economically and spiritually for so long. In fighting for equal partnerships instead of only power shifts, we all need to make sure that mistakes and oppressive patterns are never repeated. There is a need in the church for secure space to be able to give constructive criticism and to empower without being oppressive and without being perceived as oppressive. And, moreover, we need to overcome the dichotomized thinking of “them and us,” as we are all one Body, baptized with one Spirit, and we all believe in the one God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.

As I said, there is no simple answer to these challenges. But there is a key, and that key is redemption, reconciliation, and forgiveness. Every member of the Body of Christ must honestly question his or her motivation, and must reflect on how his or her culture has given or denied access to resources and power. We have to ask for forgiveness, but we also need to forgive, as we are already forgiven through the Cross.

Bianca Duemling worked at EGC with Rev. Gregg Detwiler to help prepare for the Ethnic Ministries Summit. After she returns to Germany in May, she will defend her Ph.D. dissertation on “Ethnic Churches in Germany and Integration” at the University of Heidelberg’s Institute for the Study of Christian Social Service. She was introduced to EGC through Together for Berlin, a citywide organization with networking ties to EGC. Besides her involvement in intercultural ministries, she is a founding member of “Stiftung Himmelsfels,” a foundation which fosters cooperation between ethnic churches and trains in the area of second generation youth ministry in Germany.

Guest editorial by Bianca Duemling, Intercultural Ministries Intern, Spring 2010

When the Faith of Our Fathers Collides with the Culture of our Children

While it is the nature of teens to consider their parents to be “out of touch” and the nature of older people to complain about the younger generation, the biblical mandate to pass the faith on to our children becomes extremely difficult in immigrant communities where younger people rapidly assimilate into a culture very different from their parents’. While this is not a new issue, to those experiencing the conflict, it is an issue that seems to threaten the very future of their faith.

While it is the nature of teens to consider their parents to be “out of touch” and the nature of older people to complain about the younger generation, the biblical mandate to pass the faith on to our children becomes extremely difficult in immigrant communities where younger people rapidly assimilate into a culture very different from their parents’. While this is not a new issue, to those experiencing the conflict, it is an issue that seems to threaten the very future of their faith.

In July, 2008, Drew Winkler, a Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary graduate, began working at EGC with Pastor Soliny Védrine, director of EGC’s Haitian Ministries International, sharing concerns, praying, and thinking about vision together. Because Drew has always had a heart for youth ministry, he was especially attentive to issues related to Haitian youth. One issue that grabbed his attention was the apparent growing divide between first generation Haitians (those who were born in Haiti and immigrated to the U.S. as adults) and second generation Haitians (children of first generation Haitians, born and raised in the U.S.).

Second generation Haitian youth don’t feel incorporated into their parents’ Haitian churches, and many of them look for other churches where they feel more at home. “Sometimes these youth will attend a non-Haitian church, such as Jubilee Christian Church in Mattapan, a predominately Black church that has many Haitian congregants. Other times the youth will leave the church altogether,” Drew says. Drew began discussing his concerns with his wife, Sherly, a 1.5 generation Haitian (someone born in Haiti but raised in the U.S.) and with their 1.5 and second-generation Haitian friends. He began to watch for the issue wherever he went.

In May 2009, Drew got the green light to begin in-depth research as part of his work at EGC. Drew jumped into the work with a lot of enthusiasm and a lot of plans for doing focus groups and conducting other forms of research, but all this was shelved once he realized that before he could study the Haitian community, he needed to first build strong relationships with Haitian pastors and leaders, both stateside and abroad. So Drew shadowed Pastor Sol, met with local Haitian pastors, and last year, accompanied Sol on trips to The Bahamas and the Dominican Republic, meeting Haitian leaders and youth there.

At the end of the summer, Drew began helping a local Haitian pastor with English language needs. In the process, Drew unexpectedly learned more about the perspective and values of first generation Haitians. Like many first generation Haitians, this pastor’s focus is to help Haitians come to the U.S. and understand the culture, find jobs, and learn how to become a part of society. The church’s work with the youth in their congregation focuses on helping newcomers and their children understand the language and navigate the school system. Drew’s understanding of dynamics in the Haitian church in Boston began to deepen as he worked with this pastor. “Even though we didn’t specifically talk about the second generation, just seeing the pastor’s focus and vision was really eye-opening,” he says. “There was definitely a need in his church which they were meeting.” But Drew was concerned that the church was unintentionally overlooking the needs of second generation Haitian youth.

Drew meets often with a young Haitian man working in the church community. They talk about issues they encounter, and especially first and second generation issues. “Because I have the unique perspective of being inside and outside, I’m able to help him think through decisions he’s making,” Drew says. “I can also challenge him by saying, ‘Hey, this is what first generation leaders are upset with, and you’re not purposely doing it, but this is how it can be taken.’”

After more than a year building relationships, Drew was ready to revisit some of the goals he had when he began, like organizing focus groups, or gathering leaders. But then came the earthquake, and the priorities for ministry suddenly changed. It is too soon to tell where Drew will go with this research. Meanwhile, he continues to build relationships with Haitians of all ages as they daily respond to the new pressures brought on by January’s tragedy.

by Grace Lee

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge

![Beyond Church Walls: What Christian Leaders Can Learn from Movement Chaplains [Interview]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1550010291251-EVMN3KQ15A70OBTAD4JQ/movement-chaplaincy_outdoorcitygroup.jpg)

![Ethiopian Churches in Greater Boston [map]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1506113852983-TSLLC1FENTJJGZYIO7MM/orthodox+cross+church.jpeg)

![Intercultural Leadership [Resource List]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1503082407845-5YCT4DLA93VIGHBSAN1R/pexels-intercultural.jpeg)

![Hidden Treasures: Celebrating Refugee Stories [photojournal]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1512579164575-AKNVCYX4Q5DW8IN2CNYP/P1070998.jpg)

“In June of 1972, I was discouraged because a year had gone by since I had graduated from seminary, and I hadn’t raised a penny to go back to Haiti, which had been my goal. So after preaching at a church in New York City, two ladies asked me whether they could join my wife and me for a night of prayer.